India’s apex food regulatory authority has refrained from fining or taking other punitive actions against at least 32 advertisements of various food products deemed misleading by its own committee, a nutrition advocacy and health group said on Friday.

Nutrition Advocacy in Public Interest (NAPI) also said that the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) takes one to two years to even refer complaints about misleading advertisements to the relevant committee — the advertisements and claims monitoring cell.

Such delays and inaction allow sections of the food industry to continue releasing misleading advertisements of food products, including those high in fat, salt and sugar, NAPI said in a report. It flagged concerns that such advertisements might be fuelling the consumption of unhealthy food products.

"This is gross injustice to consumers — such delays on the part of FSSAI allow companies to profit at the cost of public health," Nupur Bidla, a social scientist and member of NAPI, said. "We need objective methods to rapidly identify misleading ads for quick action by regulators."

A query sent by this newspaper to the FSSAI on Friday seeking its perspective on NAPI’s report on misleading advertisements has not evoked a reply.

The FSSAI committee had last year determined that at least 32 advertisements were "prima facie in contravention of the provisions of the Food Safety and Standards (Advertisements and Claims) Regulations 2018", the authority had itself revealed last year.

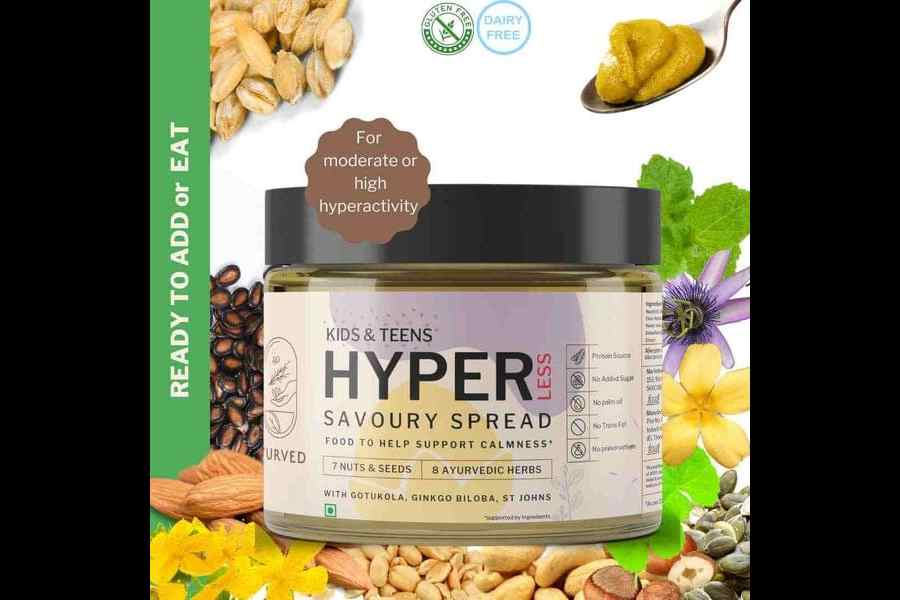

The products included a savoury paste claiming to treat hyperactivity in children and teens, an anti-diabetic rice, a millet health mix, wheat-cumin cookies, millet sweets, and a supplement to enhance focus and memory, among others.

The FSSAI has responded to a query NAPI had filed under the Right to Information Act, seeking information about fines or other punitive action imposed on the 32 misleading advertisements, saying: "No such information is available."

FSSAI documents obtained by NAPI under the RTI query suggest that in each of the 32 cases, the authority had merely sought clarifications from the companies, Bidla said.

NAPI has said that gaps and loopholes in the regulations lead to "a weakness in the process" to determine what is a misleading advertisement, because there is no objective definition in the Food Safety and Standards Act 2006.

"The Act prohibits misleading advertisements but its regulations do not have the provisions to define misleading advertisements based on nutrients of concern," NAPI has said in its report, which lists 43 advertisements, each of which, it says, "conceal(s) important information".

"An advertisement that doesn’t clearly reveal unhealthy amounts of fat, sugar, or salt should be deemed misleading," said Arun Gupta, a physician and public health expert and convenor of NAPI.

The NAPI report has listed as examples certain advertisements for confectionery, baked products, beverages including milk and dairy-based drinks, ice creams, pasta, noodles and sauces that do not reveal contents of their fat, sugar, or salt.

Gupta said that while legislative amendments to regulations may take time, the government could make changes to the rules mandating each advertisement to disclose in bold letters the amount of the nutrients of concern per 100 gram or per 100ml.