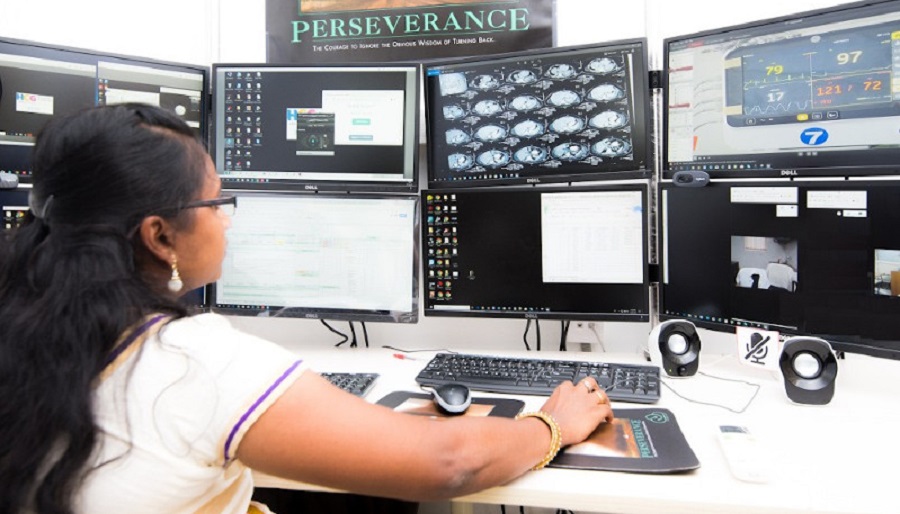

It’s the ultimate form of tele-medicine. At the Springer Healthcare command centre in Gurgaon, doctors and nurses are gazing intently into their screens and watching over 600 ICU beds in far-flung corners of the country. They’re monitoring patients in real time, dealing with emergencies and handholding doctors on the spot in remote Madhya Pradesh districts like Neemuch and Guna, Ambikapur in Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra’s Aurangabad and Sholapur. Their instructions to local medical personnel can mean the difference between life and death for patients.

Tele-medicine’s booming in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. And Springer Healthcare has also been pushed into the fast lane in the last six months. From 275 beds pre-Covid, it now has 600. They moved recently to a new district in Maharashtra, adding 40 more beds there – they’re in six districts in the state. In Haryana, where they moved in more recently, they oversee 100 beds in five districts. “Requests keep pouring in,” says Sandeep Dewan, managing director of Springer Healthcare.

It’s the same story at three-year-old Cloudphysician in Bangalore which is now being flooded by requests from hospitals wanting to click into their tele-ICU services. Cloudphysician had 150 beds in pre-Covid times but that number has shot up to 400 ever since the pandemic altered the way we live. It has been called in by the Maharashtra government which is desperately keen to get high-quality medical services to its smaller towns and rural areas in the wake of Covid-19.

Cloudphysician is working with government hospitals handling Covid-19 patients in Sangli, Nashik and Osmanabad. Even before the pandemic it had been collaborating with a Pune hospital and another in Mumbai. In its home state of Karnataka, Cloudphysician is working in Bidar, Gulbarga and even three Bangalore hospitals. “When it comes to ICU facilities, even urban areas are underserved,” notes Dileep Raman, Cloudphysician’s director and co-founder.

Seeing a patient on the screen isn’t the same as examining them in person. But India has poor medical facilities in the rural areas, is desperately short of ICU beds and most important of all, doesn’t have anywhere near enough critical care specialists or intensivists, who are crucial to ICU care. What’s more, even though they aren’t on the spot, tele-ICU doctors offer another advantage. Raman reckons that an intensivist in an ICU ward can handle about 10 patients. A tele-ICU intensivist, handholding junior doctors in a ward, can handle about 70-80 patients, he says.

That’s why tele-ICU doctors can have an impact that’s out of proportion to their number. Cloudphysician has 14 doctors and 25 nurses and, in the last six months, says it has treated 1,400 Covid-19 patients who’ve been in hospital for 8,000 patient bed days. Springer reckons its before and after figures show how big a difference, tele-ICU facilities can make. Most crucially, there are the lives saved. Dewan says fatalities have decreased by 30 per cent to 40 per cent – and that’s just by supporting the junior doctors on the spot. Other positive statistics are that 40 per cent to 50 per cent of patients are sent back to the wards more quickly. Also, using tele-ICU facilities has resulted in reducing referrals to larger cities by 30 per cent to 40 per cent.

A doctor treats a patient in an ICU of a hospital. Telegraph picture

How does it all work? First there’s a hi-definition video-camera and an audio link that allows the doctors and nurses on both sides to talk to each other. Even more crucially, patient data – everything from EGC results and oxygen levels to more detailed information — is then transmitted back to the command centre in real time on the Internet.

At the command centre, a team of doctors and critical care nurses are keeping a constant watch on patient readings. Dewan says that in an ICU, the nurses who are always present and interacting with the patients, are just as crucial as the doctors. “The nurse is the first responder and they handhold the nurses at the smaller hospitals,” says Dewan.

He adds: “The ICU outcome is very dependent on good nurses. We believe the nurses run ICUs. They are there all the time.” Springer has a team of 30 critical care nurses.

Springer’s tele-ICU unit has been in action for the last decade, growing gradually. But its growth has speeded up hugely after Covid-19 made online medical consultations a regular way of life and governments had to expand the number of ICU beds even in the most remote areas. About 350 of its beds are now dedicated to Covid-19 patients and 250 to non-Covid ones. Dewan stresses that Springer's Covid-19 work with government hospitals is being done free of cost and the expenses are being covered by grants from foundations and NGOs.

The pandemic has forced governments to move at a much faster speed than they normally would have to institute télé-medicine. It has created several 50-bed units and in some very distant Madhya Pradesh tribal areas it has even opened small five-to-six bed units. These are staffed by young MBBS and, in one or two cases, even Ayush doctors.

Raman says it took him and co-founder Dhruv Joshi a full two years of travelling to ICUs around the country to figure out exactly what support such wards needed. He and Joshi had returned from the US with the idea of starting a tele-ICU unit, but quickly found that the imported systems from giants like GE and Philips simply wouldn’t work in this country because they were designed for foreign hospitals which worked under entirely different conditions. Says Raman: “It was about frugal innovation. We had to design from scratch. We needed a system designed by Indian doctors for Indian doctors.” Raman and his partner Joshi put in all the initial capital themselves after returning from the US where they had met and worked for several years. In the last six months, they’ve received additional funding.

Cloudphysician started out by working with four private hospitals in Motihari, Muzaffarpur, Chapra and Siwan. Raman says he went to Bihar about 12 times to get the systems working just right. To make it all run smoothly “we need a robust Internet and reliable power connections,” he says.

But lately, the company has gone into fast forward mode. It went live in Gulbarga in just 11 days and it took only 15 days to rev into action in Nashik. As Nashik was launched post-Covid, the in-house team couldn’t travel across state borders so it dealt with a local tech partner. As well as its Covid beds Cloudphysician now has 170 non-Covid beds.

Training the physician on the ground is also crucial for tele-ICUs to be effective. Both Springer and Cloudphysician have training arms. And both companies insist that their mission is not about size or quick growth. Says Raman: “Healthcare is not a quick-growth industry. It’s more about taking care of patients. Growth is not what has been driving us. We want to help as many patients as we can.”