Habib Wangnoo scanned the silvery lake from the deck of his vacant houseboat hotel, remembering when he helped Mick Jagger out of a narrow, flat-bottomed canoe during the rock star’s 1981 visit to Kashmir.

Jagger spent most of the next two weeks on the boat’s upper deck, Wangnoo recalled with a smile. The lead singer of the Rolling Stones strummed his black guitar and jammed with Kashmiri folk musicians as they watched the moonlight dance across the Himalayas.

Today, Nagin Lake is desolate and quiet as a tomb, devoid even of the rowing touts who normally trawl the water. There are no tourists, no money and little hope.

“In Kashmir, tourist industry money goes into every pocket from arrival to departure, everybody lives on it,” Wangnoo said. “And now, there is nothing.”

Kashmir, the craggily beautiful region in the shadow of the Himalayas, has fallen into a state of suspended animation. Schools are closed. Lockdowns have been imposed, lifted and then reimposed.

Once a hub for both western and Indian tourists, Kashmir has been reeling for more than a year. First, India brought in security forces to clamp down on the region. Then the coronavirus struck.

The streets are full of soldiers. Military bunkers, removed years ago, are back, and at many places cleave the road. On highways, soldiers stop passenger vehicles and drag commuters out to check their identity cards.

The scene — on display during a visit by The New York Times organised and tightly controlled by the Indian government — was reminiscent of the 1990s, when an armed insurgency erupted and the Indian government deployed hundreds of thousands of troops to crush it.

Conflict in Kashmir has festered for decades. And an armed uprising has long sought self-rule. Tens of thousands of rebels, civilians and security forces have died since 1990. India and Pakistan have gone to war twice over the territory, which is split between them but claimed by both in its entirety.

Now, as India flexes its power over the region, to even call Kashmir a disputed region is a crime — sedition, according to Indian officials.

Wangnoo’s family had kept afloat during the darkest days of conflict. Through it all, visiting dignitaries, young adventure-seekers and Bollywood stars came to sunbathe on the top deck, amid the gardens of floating lotus and majestic chinar trees on the lake’s edge.

This time, the seventh-generation business — wholly dependent on tourism, like so many others in Kashmir — is at risk of going under.

Other houseboat owners have it even worse. The houseboats date to the British colonial era, a clever workaround to restrictions on foreign land ownership. But the elaborately carved cedar vessels are in ill repair and many are sinking. Hard-pressed owners are unable to pay for fresh caulk.

Onshore, people shuffle in long woollen pherans, the traditional garments that cover them from their shoulders to their shins, sipping steaming cups of saffron and almond tea and passing small pots of burning coal to keep warm.

Many say that the political paralysis is the worst it has ever been in Kashmir’s 30 years of conflict, and that people have been choked into submission.

The Narendra Modi government stripped the region of its autonomy and statehood in August 2019, and promised the move — which cancelled Kashmiris’ inheritance rights to land and jobs — would unleash a flood of new investment and opportunity for the beleaguered region.

Half a million soldiers came, imposing the strictest clampdown Kashmiris have ever seen.

The money hasn’t arrived. People say they are more scared than they have ever been. Political leaders from the wealthiest, most respected families in Kashmir — former elected officials who had worked to reconcile Kashmiris’ call for independence with India’s desire for unity — were arrested and held for months.

“You can do this to pro-India leaders, you can do it to anyone,” Mohamed Mir said from behind the counter of his father’s empty pashmina shop in downtown Srinagar.

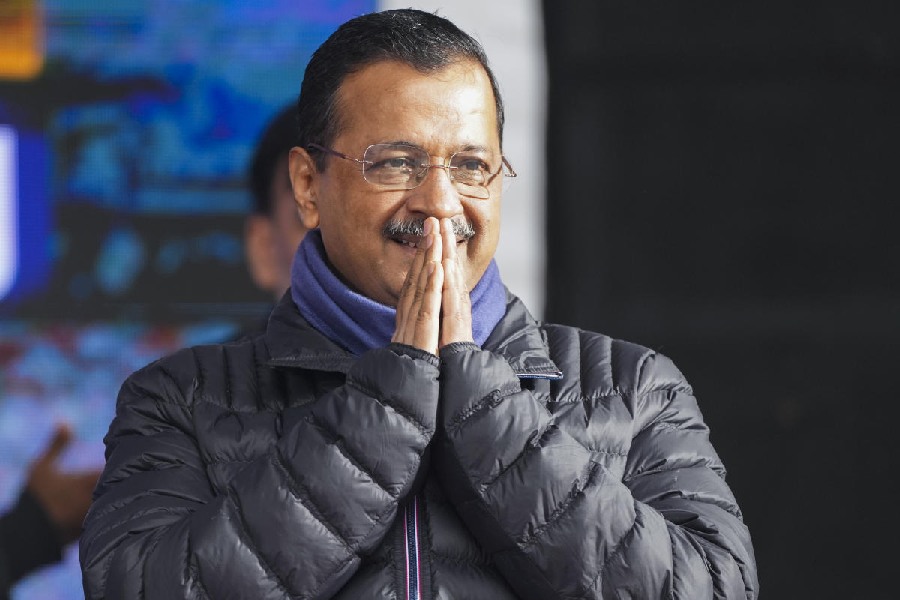

Mick Jagger Shutterstock

Kashmiris who try to vent their anger online against the Indian government are being slapped with terrorism charges. Many have been detained.

Paramilitary forces appear suddenly. They arrived at the Khanqah of Shah-Hamdan, a Sufi shrine drenched in coloured glass and papier-mâché dedicated to Mir Sayed Ali Hamadni, the Persian saint and traveller who brought Islam to the Valley.

In the evening, soldiers stood guard at the 6th-century Hindu temple on Gopadri Hill, Srinagar’s highest point, the Sankaracharya Temple, as muezzin calls to prayer from local mosques echoed across the still valley.

Kashmir’s economy is on the brink of collapse. In the past, even when gun battles between security forces and militants became pervasive, international tourists continued to throng Kashmir’s ski slopes, houseboats and artisan pashmina and papier-mâché shops.

Since Indian forces moved in, however, hardly any visitors have come.

The absence of tourists hasn’t made a difference to Ghulam Hussain Mir, whose papier-mâché jewellery boxes, bowls and vases are largely sold to overseas customers online.

But the Indian government’s communications blockade has hurt him. Internet, TV and phone service were shut off for months. When they were finally restored, the government permitted only the slowest mobile internet speeds to prevent video from reaching smartphones. Mir missed out on months of orders, and now demand for his wares in parts of the world still overcome with the coronavirus is muted.

A 700-year-old mosque a short walking distance from Mir’s home and workshop remained open through civil strife and fires. But after the Indian government took control of Kashmir, it was closed for months. Its muezzin was locked out and prevented from giving the daily calls to prayer.

“Fear is different and worse than at any time in the last 40 years,” Mir says, sitting cross-legged on a thickly carpeted floor in his workshop.

A large hive of people support tourism on Dal Lake, which the Lonely Planet guide calls “Srinagar’s jewel”. Some of Srinagar’s poorest residents live deep in the centre of the lake, in an area partially filled in and paved, and connected by a network of uneven wooden walkways.

Neighbourhoods are nicknamed after war-torn places like Kandahar and Gaza Strip. Normally, people find work driving water taxis, repairing boats, or selling tourists produce from their floating gardens. Now, except for the occasional odd job, there is no work.

“Life is under embargo because tourism is the most important industry in the city,” said Ghulam Mohammad, 56. Devoid of activity, “it’s like a jungle now,” Mohammad said, looking out over the quiet lake.

Except for a handful of Indian tourists, Wangnoo hasn’t had any guests for more than a year. Within six months, he estimates, he could lose the business and with it the dream of passing it down to the eighth generation, his sons Ibrahim and Akram, in their 20s.

“We have worked hard over these generations, we have built up the reputation. At the end of the day, it’s all gone,” Wangnoo said. “Nobody has been a friend to Kashmir except God.”

With no business to occupy him, one recent afternoon Wangnoo flipped idly through the hotel’s treasured guest book, landing on an exhortation to Sultan, his father, from Jagger: “May you always stay lite and brite.”

Wangnoo clutched the collar of his dark brown pheran as dusk settled over Nagin Lake. “There’s no brightness,” he said. “It’s looking like dark days ahead.”

New York Times News Service