A five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court on Thursday struck down the NDA government’s electoral bond scheme of 2018, which allows anonymous donations to political parties, as “unconstitutional” and “manifestly arbitrary” and saying it can help wealthy donors influence policy-making.

In its unanimous verdict that comes just ahead of a general election, the bench also ripped the shroud of secrecy around the donations of thousands of crore rupees made under the scheme.

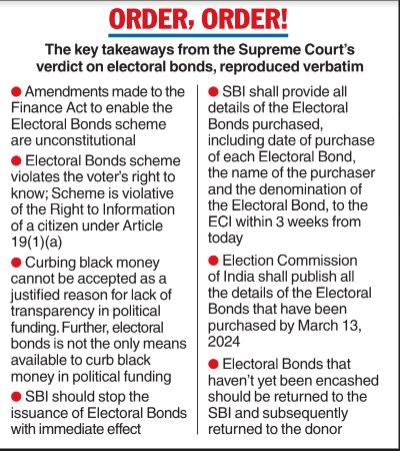

It directed the SBI to stop issuing electoral bonds and reveal to the Election Commission all the details — amount, date, donor and recipient — relating to every electoral bond purchased and cashed over the past six years.

The poll panel is to publish all these details on its website by March 13.

Writing the main judgment, Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud referred to how large, anonymous donations by the rich to the ruling party can lead to “quid pro quo” in the form of “influence over policy-making”, thus deepening “the close nexus between money and politics” and giving the donor virtually “a seat at the table”.

While the scheme allowed the donors to remain anonymous, political parties revealed annually to the Election Commission the total amount they had received via electoral bonds that financial year. According to media reports, the ruling BJP cornered the lion’s share of the donations under the scheme.

The judgment came on a batch of public-interest pleas moved by the NGO, Association for Democratic Reforms, and several others arguing the electoral bond scheme violated Article 19 (freedom of speech) and Article 21 (personal liberty), and facilitated corruption through trade-offs between corporate entities and political parties.

According to the petitioners, official data revealed that more than 90 per cent of the electoral bonds purchased were in denominations of Rs 1 crore, indicating the buyers were corporate bodies and not individuals.

However, the anonymity prevented investigating agencies such as the CBI and the Enforcement Directorate from identifying the corruption, they said.

Justice Chandrachud authored the main judgment on behalf of himself and Justices B.R. Gavai, J.B. Pardiwala and Manoj Misra, while Justice Sanjiv Khanna, the second senior-most judge in the Supreme Court, wrote a separate but concurring verdict.

“Economic inequality leads to differing levels of political engagement because of the deep association between money and politics. At a primary level, political contributions give a ‘seat at the table’ to the contributor,” Justice Chandrachud wrote.

“That is, it enhances access to legislators. This access also translates into influence over policy-making. An economically affluent person has a higher ability to make financial contributions to political parties, and there is a legitimate possibility that financial contribution to a political party would lead to quid pro quo arrangements because of the close nexus between money and politics.

“Quid pro quo arrangements could be in the form of introducing a policy change, or granting a licence to the contributor. The money that is contributed could not only influence electoral outcomes but also policies particularly because contributions are not merely limited to the campaign or pre-campaign period.

“Financial contributions could be made even after a political party or coalition of parties form(s) (the) government. The possibility of a quid pro quo arrangement in such situations is even higher. Information about political funding would enable a voter to assess if there is a correlation between policy-making and financial contributions.”

The bench rejected the Centre’s argument that by ensuring anonymity, the scheme not only disincentivised money-laundering and the stashing of black money but granted immunity to the donor from victimisation by parties to which he did not make donations.

“The contributor could physically hand over the electoral bond to an office-bearer of the political party or to the legislator belonging to the political party, or it could have been sent to the office of the political party with the name of the contributor, or the contributor could after depositing the electoral bond disclose the particulars of the contribution to a member of the political party for them to cross-verify,” Justice Chandrachud said.

He added: “Further, according to the data on contributions made through electoral bonds, ninety-four per cent of the contributions through electoral bonds have been made in the denomination of one crore.”