When everything is under lock and key, when most people would rather stay indoors than risk contagion, there is a sudden stirring in the empty jute mills of West Bengal.

Two states, Telangana and Punjab, have appealed to Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee to get the jute mills running. It is that time of the year when rabi crops are being harvested in Telangana and wheat in Punjab. According to the guidelines of the Food Corporation of India, it is mandatory that foodgrains be packed in jute or gunny bags and not plastic. But there is a shortage of gunny bags countrywide.

There are 80 functioning jute mills in India. These produce 3 lakh bales of jute a month. One bale yields 500 gunny bags. The Union ministry of textiles is currently facing a shortfall of 6.1 lakh bales.

Bengal, which has 60 mills, contributes the maximum volume of jute bags to the domestic market. “It caters to 95 per cent of the country’s demand,” says Raghav Gupta, chairman of the Indian Jute Mills Association (IJMA). That apart, jute bags are exported to Europe and the US.

At the time of Partition, there were 108 jute mills in Bengal. This is also the highest ever recorded count of jute mills in the state. Some of the largest and most well-known were the Anglo India Jute and Textiles Pvt. Ltd in Jagatdal in North 24-Parganas and Ludlow Jute and Specialities Ltd in Howrah.

“The jute industry was the spine of the colonial economy in Bengal,” says Alapan Bandyopadhyay, a bureaucrat who has done considerable research on Bengal’s ghats, where these jute mills were strategically set up. He continues, “The manufacturing sector in Great Britain developed fast and there was a huge demand for cheap and crude packaging material. Those days, Dundee in Scotland was the centre of jute production. Later, the British used Bengal to reap more profits.”

Those were such lucrative times that businessmen from Scotland set up jute mills in British India as sister companies of the mills in Scotland. In the 1850s, 100 mills came up on either side of the Hooghly river.

Samita Sen, Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History at Cambridge University, UK, says, “There are several reasons for the rise of the jute industry in the mid-19th century. In the 1870s, there was a shift from linen. The Crimean War disrupted the supply of flax, which is typically needed for the production of linen.” By the turn of the 19th century, jute bags had become an international commodity for packaging goods. But it was during World War I that the demand for jute bags shot up as they were required for transportation of goods, and for sandbagging battle trenches.

The labour composition in the jute mills changed radically in the 1890s, says Arjan de Haan, who is currently the director of Inclusive Economies at Canada’s International Development Research Centre. “Labourers started migrating from eastern Uttar Pradesh and parts of Bihar and began to settle down in Calcutta. Now, during the pandemic, people are suddenly waking up to the problems of migrant labourers. It started at least 150 years ago,” says de Haan to The Telegraph, from Ottawa, over a Skype call.

The mills spun generous profits from the mid-19th century up to the early 20th century. According to de Haan, things started declining after the Great Depression of 1929. The other change, he says, was that the Scots started leaving the country and the ownership of the mills passed into the hands of Indians.

The Partition played a cruel joke on the jute industry. Says Bandyopadhyay, “East Bengal was the chief supplier of the golden fibre. The mills were in what is now West Bengal but the crops were on the other side.” Whatever little jute grew in Gangetic West Bengal was commercially second-grade.

With Independence, the Indian government could make laws for the jute industry. The National Jute Board was formed. The industry started to operate in a more organised manner. Trade unions were formed to look out for the rights of the mill hands. By the 1970s, the industry became very sick.

When de Haan arrived in Calcutta in the 1990s to research on labour relations in the jute industry, he found that the mills had not been modernised at all. Lockouts by trade unions were bleeding them and the state government did little about it. And then, there was plastic that arrived and overwhelmed the packaging market.

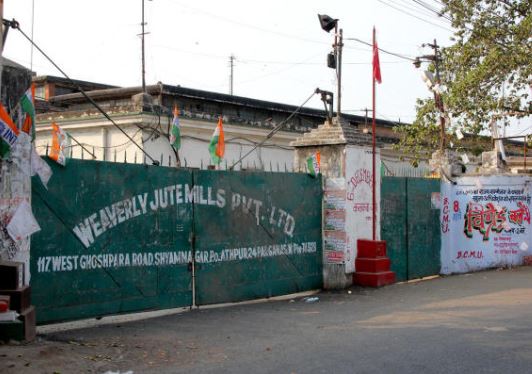

The Empire Jute Mills in Titagarh closed down in 2017. The Gondalpara Jute Mill in Chandannagore has been “temporarily closed” for a year, so also Kanoria Jute Mills and Howrah Jute Mills. Even now, the functioning 60 mills with their 2,00,000 employees, suffer frequent lockouts.

Not everyone agrees with him on this, but Gupta of IJMA believes the jute industry of Bengal has been on revival track the last three to four years. Ironies apart, will the pandemic be the much-needed shot in the arm for it? Says Anadi Sahu, the state secretary of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (Citu), “We will not let them start any of the mills unless and until we get an assurance that all the labourers will be paid for this period of lockdown, and not just those who work in the mills.”

This one’s not on corona.