India’s shortage of Covid-19 vaccines that precludes immediate inoculation for all adults is rooted in the Narendra Modi government’s lack of funding for key vaccines under development and evaluation, experts have said.

The experts, who have tracked global vaccine efforts, said the Indian government’s lack of investments contrasted with the actions of many countries, including America and Britain, that provided advance funding to vaccine makers and signed purchase pacts with them.

The Centre had last November announced a Rs 900-crore project, coordinated by the Union science ministry’s department of biotechnology, for Covid-19 vaccines.

But none of this money went to either Covishield, the AstraZeneca vaccine produced by the Serum Institute of India at Pune, or Covaxin, the home-grown vaccine made by the Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech. Instead, a part of it was given to candidate vaccines that were at more nascent stages of development.

An epidemiologist who asked not to be named described this as a “botch-up”.

The Serum Institute invested $270 million (Rs 2,012 crore) of its money and $300 million (Rs 2,236 crore) from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to build production capacity for its vaccines, while Bharat Biotech relied almost entirely on its internal resources.

The Centre covered the costs of the Covishield clinical trials by the Serum Institute and supported Bharat Biotech’s efforts through laboratory research and animal studies at the National Institute of Virology in Pune, an arm of the Indian Council of Medical Research.

The department of biotechnology had on April 16 — three months after the launch of India’s vaccination campaign — announced it would provide Rs 65 crore to Bharat Biotech to increase production from the current 10 million to 100 million doses of Covaxin per month by September 2021. It also pledged funds to three public sector units to produce an additional 35 million doses per month by September.

Covid-19 vaccines are currently being offered in India only to people 45 years or older. Health officials have underlined the “finite” supply to argue against suggestions that the campaign be widened to cover younger adults, at least in the areas hit the hardest by the pandemic.

India had by early October 2020 drawn up a tentative timeline for a Covid-19 vaccination programme — 250 million people by July 2021 — a number that has since been revised to around 350 million people.

But while the policy makers recognised the need for Covid-19 vaccines and acknowledged the Serum Institute and Bharat Biotech as the earliest possible sources of vaccines for India, the

finance to scale up production did not materialise, experts say.

“This was a botch-up — the government knew the companies’ production capacities and should have foreseen the need to ramp up manufacturing ahead of inoculations. Others did exactly this,” the epidemiologist who requested anonymity said.

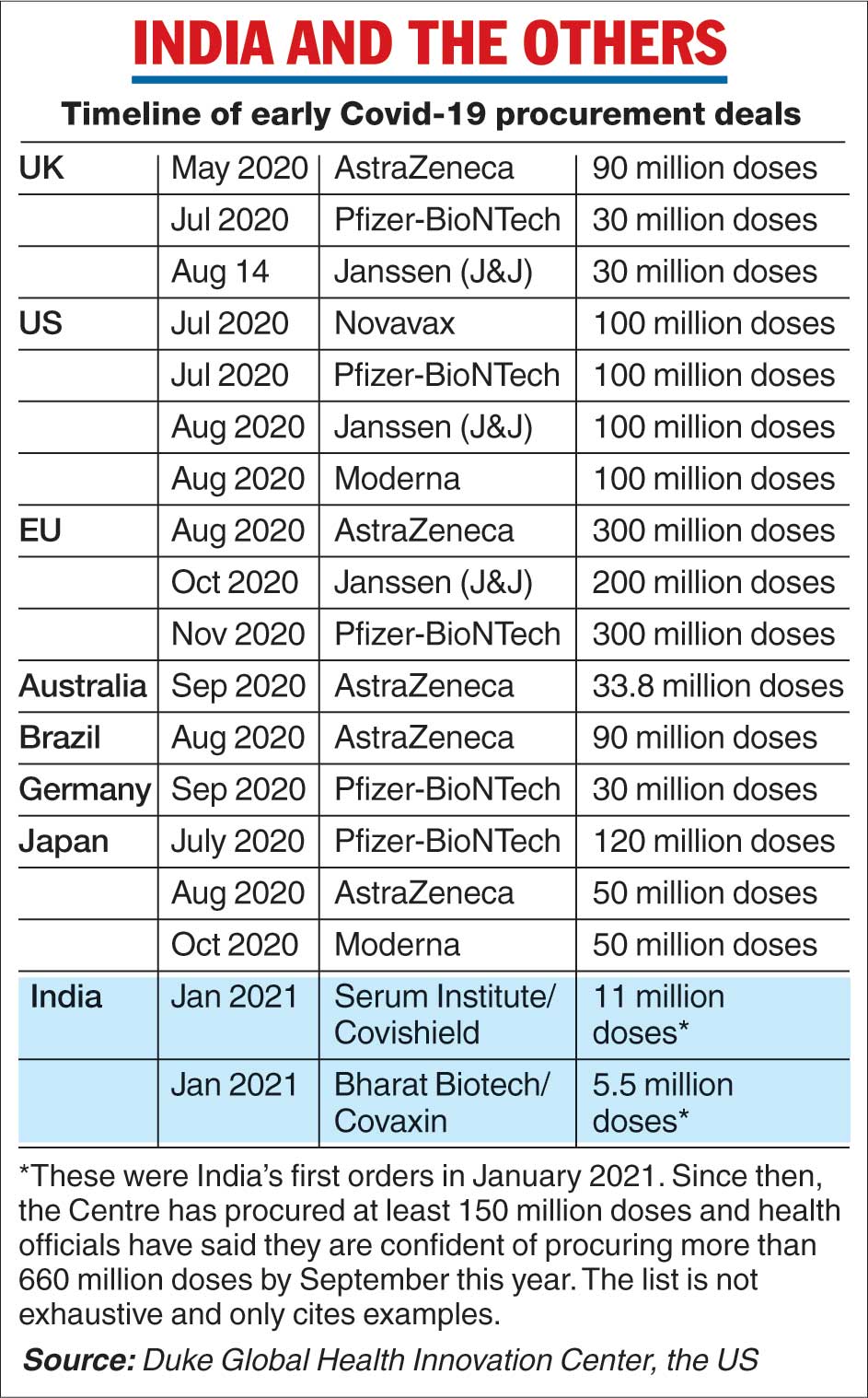

The US government invested about $6 billion (Rs 44,724 crore), distributed across several vaccine companies including Moderna, Pfizer and Janssen (Johnson and Johnson), in July and August last year on candidate vaccines that were still under evaluation.

The British government had in May last year pledged £65.5 million (Rs 488 crore) to University of Oxford researchers for work on the AstraZeneca vaccine. By October, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, and the European Union had pacts for one or more candidate vaccines. (See chart)

“Public investment in research and development and advance purchases, often at risk, has been critical for early access to vaccines,” Krishna Udayakumar, associate professor at the Duke Global Health Center in the US, told this newspaper.

Two members of India’s expert group on the Covid-19 vaccination policy and another senior government official are yet to respond to queries from this newspaper about why India did not provide early support for vaccine production.

An independent, 22-member India Task Force — a group of health experts and senior administrators — had said on April 14 that India’s current production capacity would not meet even half the monthly requirement of 150 million doses.

“It’s unfortunate. We sometimes view our private sector with great suspicion but also want them to solve our problems,” said Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the Centre for Disease Dynamics Economics and Policy, a research think tank based in the US and India.

Earlier this week, the Indian government had invited foreign vaccine makers, including Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson and Johnson, to bring their Covid-19 vaccines into the country. But experts say those companies are probably overbooked.

“There doesn’t seem to be any significant excess capacity in vaccine manufacturing anywhere in the world at the moment,” Udayakumar said. “So it’s unclear whether this action will result in significant additional doses in the next few weeks. It could make a difference over several months.”

Research funds

The department of biotechnology has committed Rs 500 crore of the Rs 900 crore Covid-19 vaccine project to supporting five candidate vaccines under advanced clinical development, three animal challenge facilities, and 19 clinical trial sites, a department official said.

The official said the department had also provided Rs 100 crore for 15 candidate vaccines under development by industry and public-sector labs.

“Three of these have moved from proof-of-concept to clinical development stage and are currently undergoing clinical trials,” said Shirshendu Mukherjee, mission director in the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council.

Among the vaccines the council has supported are a DNA vaccine from Zydus Cadila, an mRNA vaccine from Gennova, and a nasal vaccine from Bharat Biotech, he said.