Hospitalised Covid-19 patients were more likely to need oxygen and ventilation and had a significantly greater risk of dying during India’s second wave than the first, a nationwide analysis from 44 hospitals has found.

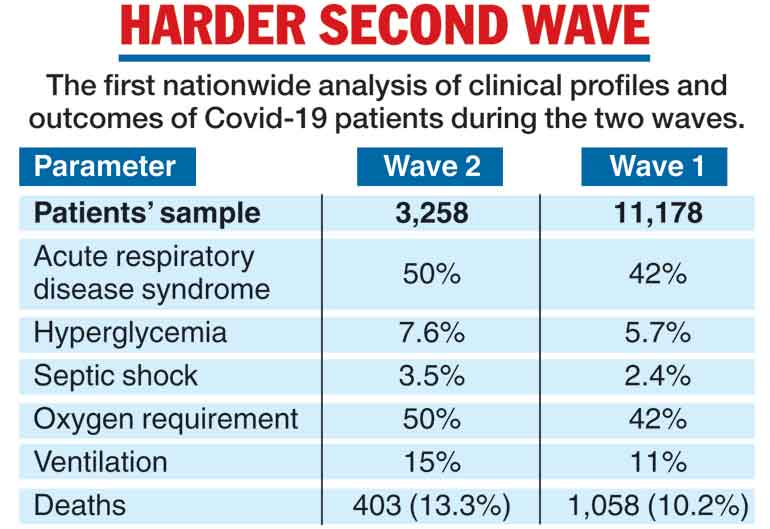

The analysis, released on Saturday by a consortium of doctors and medical researchers, has found that mortality among sampled patients during the second wave was 13.3 per cent, or 30 per cent higher than the 10.2 per cent mortality observed during the first wave.

The findings are similar to those released earlier this week by doctors from nine Max hospitals in five northern states that had found a 40 per cent increase in mortality during the second wave.

In the new study, doctors analysed clinical profiles and outcomes of over 14,000 patients from government and private hospitals across the country and observed distinct statistically significant patterns suggesting the second wave was harder on patients.

The fractions of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, hyperglycemia (uncontrolled blood sugar) and septic shock (the outcome of uncontrolled infection) were higher among patients during the second wave than during the first.

While genome studies have revealed that a highly infectious Delta variant had partly contributed to the sharp surge in cases during the second wave, researchers say there is no evidence yet to suggest that this strain contributed in any way to increased disease severity.

Instead, the study has bolstered evidence for suspicions that laxity in precautions that preceded the second wave and the resultant sharp runaway surge in which daily new infections rose 40-fold within weeks overwhelmed healthcare systems, compromising patient care.

The explosive nature of the second wave led to a large number of people being affected within a short span of time. This put the health infrastructure under pressure, making hospitalisation possible for only the most severe patients.

“This could explain the higher mortality among the hospitalised patients (during the second wave,)” the consortium led by a team of researchers at AIIMS, New Delhi, and the Indian Council of Medical Research said.

A senior infectious disease researcher who was not associated with the study said: “All deaths due to shortage of oxygen, shortage of beds and unavailable medical care could have been avoided.”