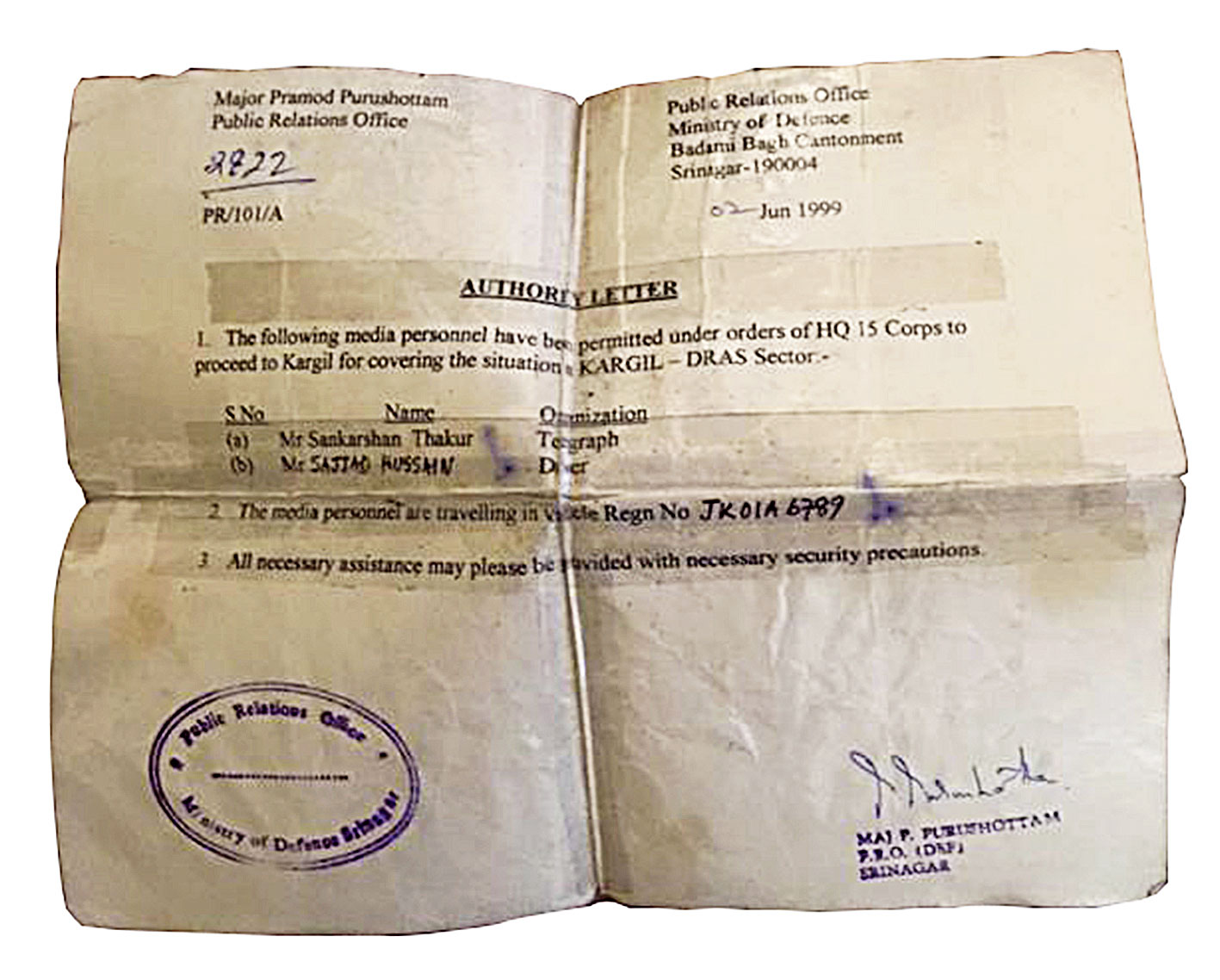

Twenty years ago, as the war over Kargil began to pirouette, was when I first went into Badami Bagh, the vast garrison headquarters of the 15th Corps on Srinagar’s southern flank. Journalists required military permits to approach the warfront — then, a tortuous 10-hour wind through Sonmarg, Zojila, Gumri, Matayen, Drass and Kaksar — and Major Pramod Purushottam signed one for me and Sajjad Hussain, who would drive me up in his rickety Ambassador. Five months later, Major Purushottam was blown apart in the first fidayeen assault on Badami Bagh.

Since then, the Badami Bagh cantonment has remained in the crosshairs of militants of one hue or another. They have mounted a fair few attempts, including a suicide bomber’s failed dare; Aafaq Shah exploded to tatters before he could sneak in. It cannot be any surprise Badami Bagh is frilled out in multiple and towering layers of concertina and steel and wears sandbags for breastplates. Crack troops and armoured vehicles guard its extensive fortification, now painted crimson and signposted with terse caution: MILITARY AREA. YOU ARE BEING WATCHED. ARMED RESPONSE TO TRESPASSING.

It is here, along this formidable bandobast of men, metal and machinery, that the route south, all the way through Anantnag, Qazigund, Jawahar Tunnel and the Banihal heights to Jammu, begins to unroll. Leithpora, where 40 CRPF jawans were cindered by an audacious car bomber on February 14, lies less than 20 kilometres down the road. That was the worst act of mayhem this carriageway has seen. But it wasn’t the first; and it mayn’t be the last. Such is the peril that attends it.

Parchment showing the author and driver Sajjad Hussain's military permit Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

The gateway announcing the new Srinagar-Jammu expressway Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

On a sunny winter’s day, you’re well entitled to bolts of rapture as you head out, past Badami Bagh and its severe arrangements against the prospect of menace. Quite suddenly, the Jhelum steers up close and begins to hug the road — a strip of muddy gold streaked by boats lumbering this way and that; before the road, any road, came about, the Jhelum was the chief carrier and transporter, the Valley’s great waterway. Past the city’s periphery, the mill of traffic left behind, the countryside begins to reveal itself, shedding dust and congestion and cacophony, layer upon layer — a countryside stripped and shivered by winter, but still able to seduce the pining eye. The divine delicacy of domes, the sun-kissed roofs of neighbourhoods clustered like they were embraced for warmth, a brooding grove

of chinars awaiting the gifts of spring, a skiff glinting on the river, a swarm of mallards squawking overhead en route to the many marshlands around, a laden bank of clouds powdering distant mountaintops with snow.

At Pampore, the first significant roadside habitation south of Srinagar, a warm waft from the ovens breaks the sylvan reverie. No more than a highway rash of retail commerce, Pampore churns out some of the most vaunted varieties of breads in the Valley. It is also the gateway to the sprawling mud promontory that yields some of the best saffron the earth has to give — tens of flat acres rolling down both sides of the road. It has now become a road leaping away ahead of itself, a six-lane two-way, like someone had rolled a ribbon down the landscape. The sky so open and enormous, it looks like the best prescription for claustrophobia. You come upon a column of outlets, arranged barracks-like and over-hewn with billboards. Saffron shops, each making feisty claims of quality excellence over the other. You’ve come upon Leithpora. You’ve come upon the scar that brought two nuclear powers to the brink of war.

It’s a tarred-over scar mid-road on the other side of the waist-high aluminium median, a cold circular scab marked out by squares painted around it. To the right, at not such a far distance, lies Pulwama, which gave to this scar its name.

For a fair part, the route runs contiguous to the Jhelum Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

Discarded security vehicles by the roadside Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

Right, left, afore, aft, whichever direction you head from here, you’ll head into boroughs so ridden with grouse and woe, they turn easily to vengeful violence. This is south Kashmir, the carbuncled cradle of militancy and terror that continues to defy the most dogged deep-ditch offensive to snuff out. To every side of this road lies a blistered geography that violently begets what it gets. Should you commit regular datelines of conflict and strife to a map, it is sure to look pitilessly pellet-ridden. Tral, Shopian, Kulgam, Shangus, Karimabad, Kakapora, Kellar, Imamsaheb, Khudwani, Sopath-Chowgam, Anantnag, Damhal-Hanjipora, Karimabad, Kokernag, Dayalgam, Samboora. Pulwama not the least. All of them and more, looped into a vicious chain of repression and reprisal, tragedy and the travesty of its repetition.

Badami Bagh, the fortified headquarters of the 15 Corps in Srinagar, from where it all begins Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

It is this ground that bred Burhan Wani, and this ground that swallowed him up in the summer of 2016. It is this ground that has, since, spawned a never-ending league of wannabe Burhans.

An exhaustive, and classified, report submitted by a top officer of the Kashmir Police early in 2016 had raised an alarm loud enough for all to hear. “…(Our) study reveals that the accessibility to social media (in the Kashmir Valley) was 25 per cent in 2010, which rose to 30 per cent in 2014 and sharply escalated to 70 per cent in 2015. The glamorization of the gun and violence gets acceptance in a small section of young, impressionable minds who consider themselves at the receiving end in the contemporary political scenario,” said the report driven by former IGP (CID) of the state police, Abdul Ghani Mir.

A warning sign on the walls of the Badami Bagh army camp Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

Perhaps the sharpest observation in Mir’s report was this: the steep climb in social media access had coincided with the swift burgeoning of Burhan Wani’s reputation, built largely out of accessing social media networks from his hideouts. By the time he was gunned down in South Kashmir’s Duroo bush, Burhan had become Kashmir’s most followed social media entity — his face was on every other youngster’s phone, he dominated WhatsApp chats, his video exhorts to “liberation” were ubiquitous on Internet platforms. Burhan, and the mythology around him, have turned into a raving ghost that refuses to be spooked.

Another critical issue Mir flagged was how South Kashmir, the home base of former Jammu and Kashmir chief minister Mehbooba Mufti and her People’s Democratic Party (PDP), had become the Valley’s chief nursery of militancy by far. Of the 156 fresh recruits to militancy the study focused on, 99 belonged to the South Kashmir pockets of Pulwama, Anantnag, Kulgam, Awantipora and Shopian. Burhan came from a village in Tral in Pulwama, known to be a hardcore enclave of militancy.

The EDI complex near Pampore which has seen repeated gun battles with militants Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

The report had, in fact, named Burhan as one of those in the police/intelligence sights, described his background and put a partly empathetic diagnosis on how and why a teenager like him comes to embrace arms: “The militant’s family are sympathisers of Jamaat-e-Islami. Militant comes from Hanafiat (Hanafi sect) but is a Jamaat sympathizer. Attended a local ‘darasgah’ (religious seminary) in Naibugh, which is being run by Jamaat sympathisers. The militant is also habitual of attending Jamaat ijtemas (gatherings). Militant was an OGW (overground worker) for one month and was closely linked to a militant named Shabir Ahmad Bhat of Hyhama. The militant was harassed/beaten by SOG (Special Operations Group), Tral, frequently. The subject considers himself a victim of State action. Militant lost his brother in an encounter with security forces. Peers of the militant were distractive in nature. Among the peers of the militant three are OGWs, one has been killed, one released and one involved in stone-pelting case. The immediate influence of such a combination is quite evident. Peer group seems to be the dominant reason for his joining militancy. There are three active militants, 38 killed and 34 released/ surrendered in the vicinity of the militant....”

Where the country road from Pulwama enters the national highway Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

Little wonder, it has also seen the most number of security-led encounters in which more than a 100 militants, marked out and previously unknown, have been killed in a fiercely mounted campaign to stamp them out over the last year. But the consequences have refused to abate. Huge numbers of village folk, women and children included, have turned out to disrupt security operations and, quite often, to afford militants an escape. Each major hit scored by security forces has culminated in rippling funeral processions — as rapturous as they are fevered and belligerent. Each fallen militant has inspired another, or several others, to follow suit.

The road here opens up onto a promontory where Kashmir’s famed saffron is cultivated Photograph by Sankarshan Thakur

Adil Dar, the mass murderer of Leithpora, was not the only one in his vicinity strapped with explosives and determined to perish with a toll of men. There was too, lurking in the wings, another fidayeen bomber, readied by his undercover masters and waiting to strike: Raquib Ahmed, a Shopian boy. What revealed him and his plot was a video that surfaced of his would-be suicide mission. But by then, Raquib had already been killed in a gunfight in Kulgam. But who’s to tell how many are in the nurturing in this tragic nursery of carnage?

Through such a minefield did the security bosses think it fit to roll down a caravan of 78 troop-laden trucks.