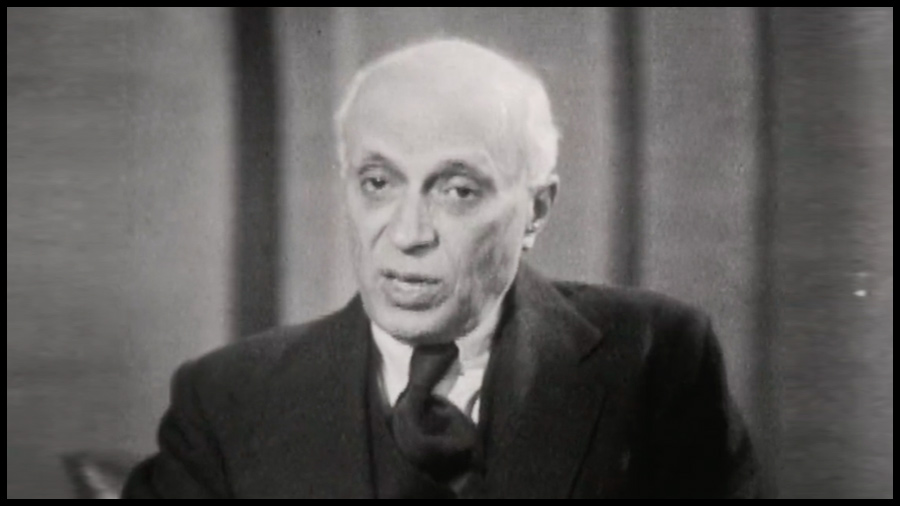

It’s a half-hour news show that is visibly from another era. Television was still a relatively new medium when Pandit Nehru arrived in London in June 1953 for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Press Conference, the programme on which Nehru appeared, was described as a programme in which, “Men who make the news answer questions from men (no women, of course) who write the news.”

Emphasising the almost amateur nature of the proceedings, the show’s presenter William Clark tells Nehru: “I am very grateful to you for coming here. I am particularly grateful because I believe this is your very first appearance on television.”

“Yes,” replies Nehru, with a small smile: “This is the first time I am facing this ordeal. In fact, I know very little about television, except what I’ve heard about it.” The seven-minute clip of the half-hour show has just been released by the BBC Archives.

Asking the questions were the top stars of British media – but who also appear like television novices. Kingsley Martin, editor, the New Statesman and Nation, was one such interviewer. From The Sunday Times there was the newspaper’s editor H. V. Hodson and also Donald McLachlan who was The Economist foreign editor.

Nehru would surely have received an F grade from any modern public relations consultant for his performance. First and foremost, he would have been quickly ordered to take his hand away from his face during his debut television interview. He might have been asked to look his interlocutors straight in the face and address them with absolute certitude. Waffle and uncertainty aren’t allowed in modern television or public relations.

Most of the exchanges are almost inconceivable today. About the Commonwealth, Nehru mentions differences between the gathered statesmen but he sees them as a path to better mutual comprehension. “These different viewpoints come up …. maybe, if you like, slightly clash but in a friendly way.” These friendly clashes, he insists, “lead to a better understanding.” Hard to imagine any modern politician talking that way about the G7 or G20 summits.

Nehru would, of course, get full marks for being impressively well-turned out in what was surely a Saville Row suit and tie impeccably knotted. Could his casual confidence have been mistaken by a PR consultant for possible arrogance? That laidback, offhand manner might have got the thumbs down. Throughout the interview, he kept his hand either on the side of his face, or below his chin looking thoughtful.

The question that Nehru fielded brilliantly was on why there was “so little resentment in India towards the British in view of our past history. It seems to us that India is a most wonderful magnanimous country. Can you explain this remarkable phenomenon of forgiveness?” asked the New Statesman’s Martin.

Was Martin's question designed to bring a gushing reply about how wonderful British rule had been? Probably not. Martin had been a conscientious objector during World War I and was a staunch socialist. He was unlikely to be looking to praise the British Raj.

Nevertheless, the question raised a momentary smile from Nehru, who starts by saying, “Well partly because we don’t hate for long or intensively.” But then he crucially adds that the lack of rancour was, “partly because of the past background that Mr Gandhi gave us during all these past decades.”

Martin doesn’t give up and, as a follow-up, points out: “You were in prison yourself for 16 years and you don’t seem to have any resentment about it at all. Astonishing thing really.”

Nehru’s genial answer is startling for a modern reader. He says: “I think it is a good thing for a person to go to prison for a short while.”

Hodson takes up the baton, asking what were Nehru’s greatest successes and failures after being prime minister for seven years. There’s a slight frown on his face as he says: “What troubles us chiefly is the economic side. I believe we have made progress. I would like the progress to be much faster.”

On the political front, he points out several achievements like absorbing the princely states into independent India and the first general elections that had just been held in 1951. “We’ve had these general elections which were remarkable on a tremendous scale and we’ve built up a good democratic structure,” says Nehru.

Some of the questions betray an almost complete lack of understanding of anything that is not the British point of view. Hodson asks whether the Anglo-American or British American agreement, “have a special value for the defence of our common ideals of democracy.”

Nehru points out gently that the world looks very different when looked at Delhi or Karachi as it looks from London or Washington. To explain, he says: “Take the question of China. China is a distant country to most people in Europe and America. China is a country having a 2,000-mile frontier to India. Well, it is a different picture to us immediately.”

When the show ends, Nehru generously says: “I haven’t found this half hour quite so bad as I expected it to be. In fact it has passed rather rapidly. I was surprised that it was over. Perhaps because your questions were interesting and I got involved in them. Anyway, it has been a pleasant time and I thank you for it.”

1/4

1/4