The Modi government came out with new national income statistics that jacked up the GDP growth rate in 2017-18 to 7.2 per cent from an earlier estimate of 6.7 per cent on a day its image lay in tatters after leaked jobs data showed that the unemployment rate had surged to a 45-year high of 6.1 per cent.

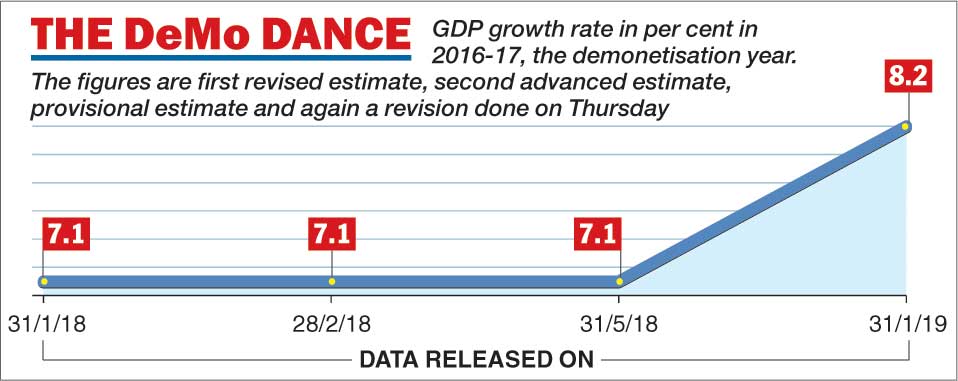

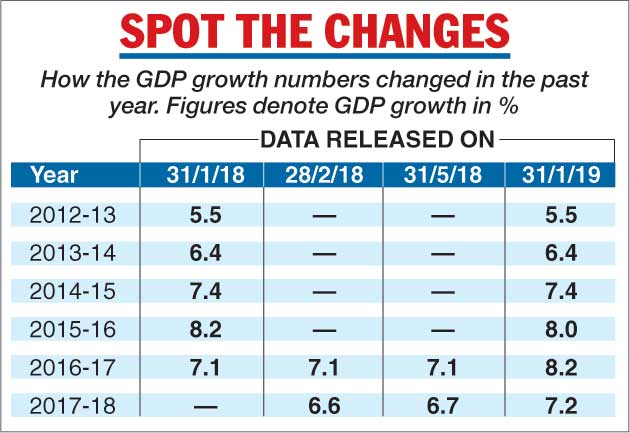

The biggest surprise in the first revised estimates of the Central Statistics Office (CSO) was the dramatic upward revision in the GDP growth rate for 2016-17 — the year in which the demonetisation occurred — from 7.1 per cent to 8.2 per cent.

The earlier estimate of 6.7 per cent GDP growth for 2017-18 had been released just a month ago. While data revisions are usually done on the basis of new findings and collations, the revision of the estimate within a month is seen as surprising.

M. Govinda Rao, a former member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council, said: “Such a quick upward revision by half-a-percentage point is surprising. There is a need to study the basis for this data revision.”

The revisions meant that the five-year Modi regime wasn’t going to have a single year when GDP growth has been lower than 7 per cent.

What really stretched credulity was the CSO’s assertion that economic growth during the Modi years had been the highest in the year of the demonetisation, confounding forecasts by many economists that the reckless move would knock at least two percentage points off the trend growth rate.

Telegraph picture

“Real GDP or GDP at constant (2011-12) prices for 2017-18 and 2016-17 stand at Rs 131.80 lakh crore and Rs 122.98 lakh crore, respectively, showing growth of 7.2 per cent during 2017-18 and 8.2 per cent during 2016-17,” the CSO said.

The CSO also trimmed the growth rate for 2015-16 to 8 per cent from the year-ago estimate of 8.2 per cent.

In terms of absolute numbers, the real GDP figure for 2015-16 was cut by Rs 16,652 crore to Rs 113,69,493 crore while the number for 2016-17 was raised by Rs 1,02,321 crore to Rs 122,98,327 crore.

The CSO said the revisions in the GDP numbers for the prior years was largely on account of updated estimates from a variety of datasets, the replacement of “Revised Estimates” of different items of expenditure and receipts in the central and state government budgets by “Actuals” and the use of latest data received for cooperative banks, non-banking financial institutions and financial auxiliaries.

Economists remained sceptical about the latest growth estimates which were put out just a day before the Modi government presents its interim budget ahead of the general election later this year.

The upward revision for 2016-17 by 1.1 percentage points and by 0.5 percentage point for 2017-18 are being seen as inordinately high and not backed by actual industrial and service sector growth rates for that period.

The CSO said: “The First Revised Estimates for 2017-18 have been compiled using industry-wise/institution-wise detailed information instead of using the benchmark-indicator method employed at the time of release of Provisional Estimates on May 31, 2018.”

Telegraph picture

Economists said one of the reasons for the sudden upward revision could be to show the fiscal deficit, which is calculated as a percentage of the GDP, in a better light.

The fiscal deficit expressed as a percentage of the GDP for 2018-19 had been projected as 3.3 per cent by former finance minister Arun Jaitley in last year’s budget, whereas the fiscal deficit for 2017-18 was estimated at 3.5 per cent.

During 2017-18, the growth rates of primary (agriculture, forestry, fishing and mining and quarrying), secondary (manufacturing, electricity, gas, water supply and other utility services, and construction) and tertiary (services) sectors have been estimated at 5 per cent, 6 per cent and 8.1 per cent as against 6.8 per cent, 7.5 per cent and 8.4 per cent, respectively, in the previous year.

Economists also find it difficult to swallow the sectoral growth revisions. The gross value added (GVA) by the primary or agricultural sector is shown as growing by 5 per cent instead of 3.3 per cent in 2017-2018, while the secondary or mostly industrial sector is shown growing at 6 per cent instead of 5.8 per cent, and the tertiary or services sector at 8.1 per cent instead of 7.9 per cent.

“The huge increase in the agriculture sector at a time when everybody is talking about a farm crisis is surprising,” said Biswajit Dhar of Jawaharlal Nehru University. The agrarian crisis has seen several state governments waiving loans through 2017-18 and more recently last December.

The government is also believed to be readying a farm package in the interim budget to alleviate agricultural distress.

The data revision in the farming sector comes during a phase when lower prices had accentuated the agrarian crisis, Dhar said.

Questions are being raised not only in academic circles but also among investors and merchant bankers about the reliability of Indian data.

“Earlier we used to boast of a very high quality of our economic data. In fact, foreign investors and bankers used to tell us that we tend to underestimate our data rather than overestimate it. Now, of course, our figures are being compared to Chinese or Russian data handouts,” said Amit Bannerjee, an independent merchant banker, specialising in East Asian Funds.

Chinese and Russian economic data are always taken with a pinch of salt by global investors and academics.

“The resignations by independent members of the National Statistical Commission and controversy over GDP data do not show India’s data releases in a good light,” Rao said.