The family gathers around the laptop in New Delhi once a week. Sometimes, relatives dial in from north India, or even the United States. They wait for Umar Khalid, 37, an Indian political activist, to appear on the screen from jail.

“How are you, Ammi?” Khalid boomed one recent day, addressing his mother, Sabiha Khanam.

“Everyone get in the frame, please,” he urged when he was unable to see a face but could hear a familiar voice.

In early 2020, Khalid became one of the most prominent figures of India’s biggest and most energized protests in a generation, a three-month outpouring of opposition to government proposals widely seen as anti-Muslim.

He was arrested later that year, and he has now languished in jail for four years without a trial, making him a symbol of the wide-ranging suppression of dissent under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. It continues unabated even with Modi’s reduced mandate after elections in the spring.

To silence opponents like Khalid, Modi’s government has increasingly turned to a draconian state security law that in the past was used only to quell violent insurgencies. Activists and other dissenters targeted under the law can be held in pretrial detention almost indefinitely. Some have died while awaiting bail. Even if they do move toward trial, defendants are often bogged down in years of legal battles.

Syed Qasim Rasool Ilyas, left, and Sabiha Khanam, Umar Khalid’s parents, talk on a video call with their imprisoned son from their home in New Delhi, Oct. 15, 2024. (Saumya Khandelwal/The New York Times)

Modi’s government has worked to bend the judicial system to its will and wield it as a weapon against a range of adversaries. When the dissenting voice is Muslim, as in Khalid’s case, the hammer brandished by the Hindu-nationalist government comes down even harder, activists and family members say.

Khalid was detained under the state security law after he made anti-government speeches and participated in WhatsApp groups that were organizing protests. He was accused of instigating riots in Delhi that left more than 50 people dead. Most of the victims were Muslims who died at the hands of Hindu mobs.

Ever since, he and his family have been caught in a cruel routine.

Khalid’s application for bail was rejected three times in lower courts, said his father, Syed Qasim Rasool Ilyas. His bail hearing in the country’s highest court has been postponed at least a dozen times. On at least two occasions, Khalid has been taken to court, only for the judge to recuse himself and send the defendant back to his cell.

“As they say, the process is the punishment,” Ilyas said. “Sometimes the judge recuses himself, sometimes the lawyers are not available.”

In India today, “one has to pay a price for speaking the truth,” Ilyas said. “And it is very easy to frame someone with a Muslim name these days.”

Khalid challenged Modi just as the prime minister was riding high after a sweeping election victory in 2019, which cemented his position as India’s most powerful leader in decades.

Banojyotsna Lahiri, Umar Khalid’s partner, at her home in New Delhi, Oct. 15, 2024. (Saumya Khandelwal/The New York Times)

After the election, Modi moved swiftly on a slate of divisive policies advancing the longtime wishes of his Hindu-nationalist support base.

He revoked the special autonomous status of the Muslim-majority Kashmir region. He laid the foundation stone for a grand Hindu temple to be built at a site long disputed between Hindus and Muslims. His government announced plans for a national citizen registry that was widely seen as potentially denying citizenship to Muslims.

Protests erupted after the government passed a law granting a path to Indian citizenship to persecuted Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from nearby countries who had been living in India. Muslims were pointedly excluded.

The government said the law was not about Indian Muslims, but instead about giving oppressed minorities in India’s neighborhood a new start.

But many Muslims in India saw the measure as part of a design. Once the citizen registry went into effect, they feared, they would be deprived of citizenship if they could not present proof of lineage in India.

The protests over the citizenship law spread quickly. In the Delhi neighborhood of Shaheen Bagh, thousands of women held a sit-in for months. Braving one of the coldest Delhi winters, with children in tow, they gathered under a huge yellow and pink tarpaulin day and night.

Long before the protests, Khalid — who has a doctorate in history from Jawaharlal Nehru University, long an incubator of peaceful dissent — had been speaking out against anti-Muslim hatred.

He was particularly troubled by the increased ghettoization in India’s capital, where Muslims had long received fewer benefits from the state but felt the arm of the law more forcefully.

“We don’t get pizzas delivered here, we don’t get internet connection, we don’t even get home loans,” he says in a 2009 documentary about ghettoization, when he was still a young student.

He became more vocal after Modi’s rise to national power, which injected deeper violence into the existing anti-Muslim prejudice. When hate crimes and lynchings became routine, with Modi and his lieutenants maintaining a silence, Khalid attended rallies where he railed against Modi’s divisive politics and called his close aides “fascists.”

During the protests against the citizenship law, Khalid said in a speech to the women gathered in Delhi that “we will fight this fight with a smile and in a nonviolent way on the streets of our country.”

“This is a gathering of people who love Gandhi,” he said.

The protests to that point had remained peaceful. But widespread violence broke out in Delhi in early 2020 after right-wing groups and leaders of Modi’s party made provocative statements about the demonstrators. At one rally, a few weeks before the violence erupted, a government minister led a call-and-response chant saying that protesters should be shot as traitors.

Even as Muslims made up a majority of those killed in the riots, the state’s wrath was one-sided against Muslims. The police rounded up young Muslims, embroiling them in cases that would unravel one after another for lack of evidence or because the police were found to have taken part in violence against Muslims. At the same time, leaders of the governing party who had called for violence remained untouched.

After four years in jail, Khalid is described as having mellowed. He plays cricket and helps other inmates with their bail applications, his friend Apeksha Priyadarshini said. Sometimes he gets to feed cats that stop by his cell. His partner, Banojyotsna Lahiri, shares with Khalid cards and letters of support that come in the mail and keeps up a regular supply of books.

His parents and siblings, who live in an elegant apartment in south Delhi, must endure a torturous wait.

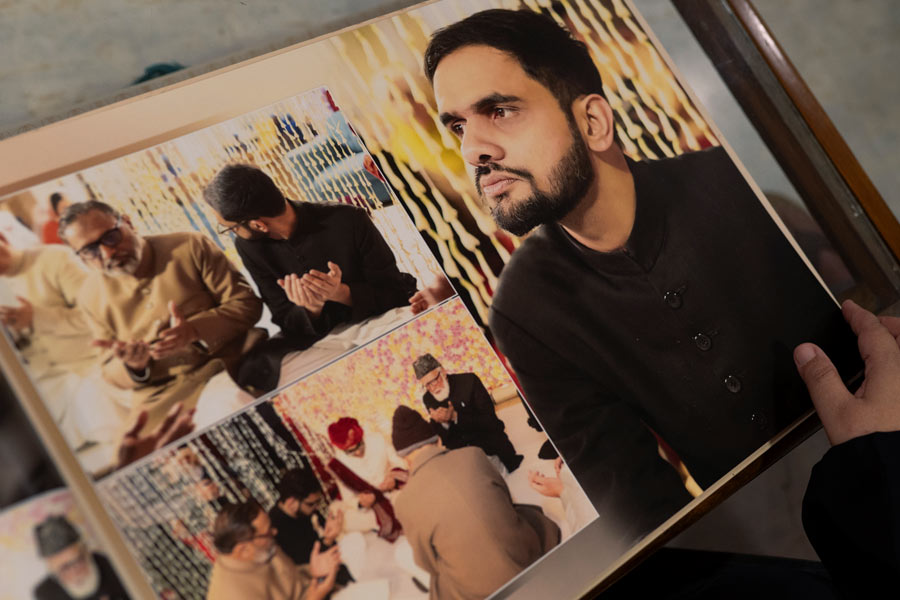

Last winter, Khalid was allowed to leave jail for a week for his sister’s wedding. In a photo album, he looked dapper in a dark blue kurta and a Nehru jacket.

“He did not sleep a wink for days,” said Khanam, his mother, a soft-spoken woman who wears a hijab. “He was scared of losing out on family time to sleep.”

While the bail hearings by now seem to be empty exercises, the family finds solace in seeing him up close in court. At a hearing this summer, his mother briefly held Khalid’s hand. When it ended, the judge said that mother and son could sit for a brief chat — six minutes.

“I hugged him hard and prayed for his release,” Khanam said.

The New York Times News Service