Zoramthanga is five foot nearly nothing but do not be misled by his diminutive frame, or even his beguiling smile. At 76, the three-time chief minister of Mizoram still packs a punch. Consider, for a start, that he fought alongside the Pakistani army during the 1971 war and was then able to change course to hold extended reign in high public office. On more than one occasion, Zoramthanga tells me with relish, “We orchestrated our daring escapes from Indian custody, including one from the headquarters of the Intelligence Bureau, in typical James Bond style.” It took 20 years of a devastating insurgency to restore peace in the tiny northeastern state of 12 lakh people tucked between Myanmar and Bangladesh; on June 30, 1986, the Mizoram Peace Accord, arguably modern India’s most durable such agreement, was finally signed. Mizoram has never looked back.

Zoramthanga recalled to me flashes of the turbulent days leading to the final laying down of arms by the firebrand guerrillas of the Mizo National Front (MNF) led by the legendary Pu Laldenga.

Having graduated from a college in Manipur in 1966, Zoramthanga joined the MNF’s armed underground ranks to wage a freedom war against India. He served as secretary for the Run Bung area for three years, living and fighting from the bush. In 1969, he became secretary to Laldenga and accompanied him to East Pakistan. “After the fall of Dhaka in the Bangladesh war, we escaped miraculously to Rangoon [now Yangon] pretending to be refugees headed for Myanmar. In March 1972, we fled from Rangoon to Karachi on a Pakistani charter flight. Laldenga, his family, three others and I then moved to Islamabad for four years,” he recollects. “Around that time, we made contact with the Indian government secretly (behind Pakistan’s back) through Kabul. We landed in Delhi in January 1976 for talks. These ‘talks’ lasted for 10 years and culminated in the accord.”

All this while, Mizoram, then a Union Territory, remained wracked by violent insurgency. Zoramthanga went underground and operated from the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. “In 1979, Morarji Desai, then Prime Minister, told us to hand over arms. We said first negotiate, then we will surrender arms.” The Centre responded by detaining the MNF leaders at the IB headquarters in New Delhi. “But we devised an audacious escape route and managed to board a flight to Calcutta. We then flew to Silchar in Assam (there being no airport in Mizoram at the time) and boarded a jeep to reach the Mizo jungles. I remember we walked for 27 days thereafter. Subsequently, I became the vice-president of MNF as Laldenga was in Delhi. Laldenga was incarcerated in Tihar jail, but was finally released and allowed to go to London.”

While Zoramthanga oversaw operations from the jungle headquarters in Mizoram, “between 1980 and 1986, we negotiated with the government in Delhi through those whom I delegated. I did not go to Delhi again. I supervised the underground movement.”

The chief minister has put down his memoirs — “You will find all the adventures of my insurgent days there” — and hopes to publish them once the pandemic abates. He hopes, too, that some Hollywood producer — “not Bollywood” he is quite sure — will find in them the masala to churn out a blockbuster.

In 1986, the Mizoram accord was signed. In his book on this historic event titled Lest We Forget, L.R. Sailo, press secretary to the chief minister of Mizoram for years and now regional director of the Indian Institute of Mass Communication in Aizawl, aptly says this was “the only insurgency in the world that ended with the stroke of a pen”.

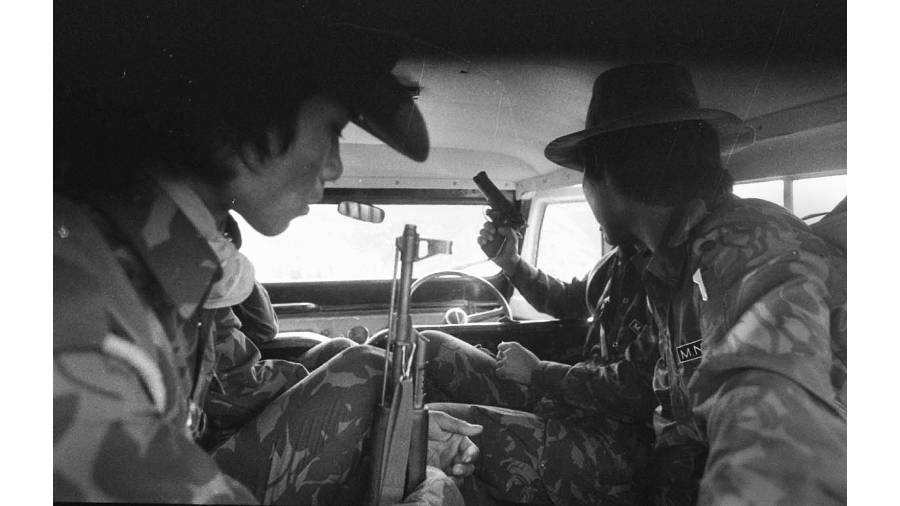

Pu Laldenga (seated, centre) with wife Biakdiki (right), Zoramthanga (left) and other MNF guerrillas File Picture

The view is shared by Zoramthanga’s predecessor and five-time chief minister, Lal Thanhawla, the Congress veteran who had to step down to allow Laldenga to take his place in 1986 to ensure smooth transfer to truce. “The historic accord is the most successful one to have been signed in this country,” the 83-year-old said from his home in Aizawl.

Mizoram earned its statehood after the accord, in 1987, with special protection in the form of the Inner-line Permit, land and customary laws.

In that interim government, Zoramthanga was a cabinet minister. He became the MNF president when Laldenga died in 1990 and has helmed the party ever since.

Asked if all the clauses of the accord had been implemented, he says: “We are yet to get a separate high court. Rehabilitation of the returnees is still unsatisfactory. But our resounding success was that not a single person went underground again. That is why Mizoram is today an island of peace and the accord is a success.”

He rues that the accord anniversary this week cannot be celebrated as it ought to be, because of the pandemic. “We will mark the occasion, but we are disciplined,” he adds.

On his part, Lal Thanhawla graciously acknowledges his takeaways from the years of governance of a state that was not only disturbed but lacking in economic development. “The civilian population was caught in the crossfire between the insurgents and the army.

The forced eviction of villagers and herding them like cattle into cluster settlements resulted in famine and acute poverty. Their homes were burnt down so that the insurgents could not use them for refuge. Finally, the accord ushered in complete peace and saved countless lives.”

Asked whether his sacrificing the chief ministerial chair had reaped dividends, Lal Thanhawla says, “Political problems cannot be solved through the barrel of a gun or by military might. They need to be solved through negotiations. We have to create a conducive atmosphere, ensure the people’s co-operation as well as a willing bureaucracy. Whoever comes forward for negotiations should be welcomed with open arms. Finally, there has to be give-and-take… the return of peace was most important for the disturbed state. It is very difficult to restore peace, even more difficult to maintain it. Throughout my five terms as chief minister, I have strived for development. Our per capita income was the highest in India 2017 onwards. The GDP grew significantly.” Mizoram’s remarkable literacy graph and its green initiative have also earned applause.

In a nation whose parts remain riven with thwarted aspiration and civil-military strife, Mizoram remains a unique and durable narrative of peace, hinged on an ability to sacrifice power for a larger cause and skillful conflict management. Only such values could enable not one but two armed guerrillas to transition from the jungles to heads of democratically elected governments.