Aslam Ansari has had no work for the past four days.

The migrant worker wants to go back home not for fear of catching Covid but to escape starvation.

The tailor and his family of six live in a one-room dwelling close to Kalwa police station in Thane, near Mumbai. On Thursday, the family from Dumri block in Giridih, Jharkhand, had rations to last just three to four days.

“Once the food runs out, we’ll return to Jharkhand. I have tried very hard; there’s no work now,” said Aslam, who worked at a factory, stitching clothes for small children and earning about Rs 15,000 a month.

The Centre claims it has implemented a “one nation, one ration card” scheme to enable migrant workers to secure subsidised food from their nearest fair-price shops under the public distribution system. But Aslam said he does not receive subsidised food in Thane.

“We are not scared of the corona(virus); our main worry is the unavailability of work. We cannot survive here without an income. There’s no help from any quarter,” Aslam said.

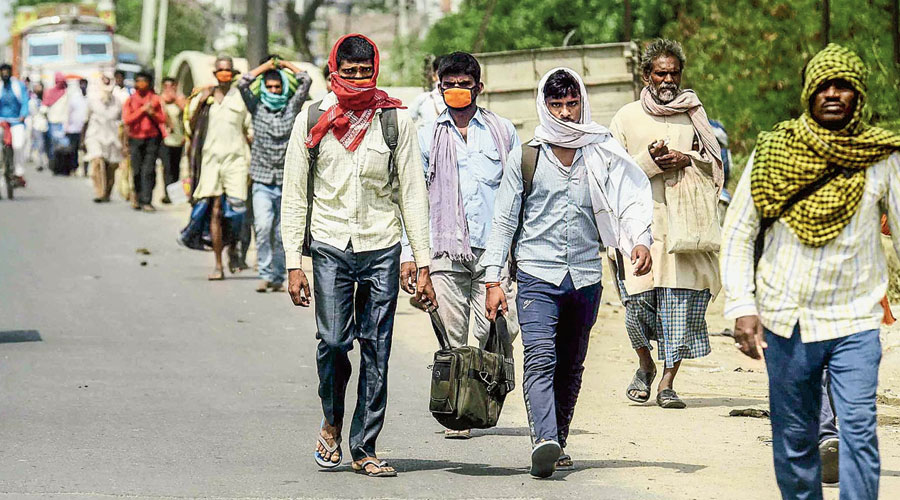

Labour economists have highlighted how the loss of work and the absence of government support are forcing migrants to leave their workplaces, especially in states where restrictions and curfews to contain the second wave of the pandemic have constrained economic activity.

Small establishments have stopped operations and construction has been hamstrung in these states over the past two to three weeks. Railway stations and inter-state bus terminals in the major cities are crowded with home-bound migrants.

According to data released by the private research group, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, the national unemployment rate increased from 6.65 per cent to 8.58 per cent between March 28 and April 11. Urban unemployment rose from 7.72 per cent to 9.81 per cent while the rural figure jumped from 6.18 per cent to 8 per cent.

Amitabh Kundu, a Distinguished Fellow at the Research and Information System, said migrants were returning home primarily because their earnings had stopped or were likely to stop in a few weeks. They didn’t want to be trapped like they or their peers were last year when the pandemic broke out.

“Migrant workers cannot survive even a month without work. They have to pay Rs 2,000 to Rs 3,000 as rent every month besides meeting other daily expenses,” Kundu said.

“Unless they earn at least Rs 10,000, they cannot live in a city like Mumbai. Their major concern is not the coronavirus but job losses.”

Kundu said the formal sector too would be hit by the pandemic’s resurgence because of a “lack of demand for their products in the market, poor labour supply and non-availability of cheap intermediate outputs from the informal sector”.

He said that when Covid had first arrived from abroad, it was confined largely to the rich, middle classes and the elderly. It spread sluggishly during the initial months since these groups’ social interactions with the working class were limited.

But now the pandemic had penetrated habitations with dense populations, such as slums with their congested dwellings where people share toilets and taps, Kundu said.

The 2011 census found 39.4 per cent households in rural areas and 32.1 per cent in urban areas living in one-room dwellings.

Kundu underlined the need to strengthen insurance schemes for the workers and the jobless.

Labour economist K.R. Shyam Sundar, professor of human resource management at XLRI, Xavier School of Management, Jamshedpur, said the four labour laws passed in Parliament over the past two years do not provide for an allowance or insurance for the unemployed.

“The government has not learnt the important lessons from its experiences in dealing with the first phase of Covid. There is no provision in the social security code for an unemployment allowance,” Sundar said.

“The government missed a golden opportunity to design a universal unemployment assistance scheme and unemployment insurance scheme.”

In his recently published book, Impact of Covid-19, Reforms and Poor Governance on Labour Rights, Sundar has highlighted India’s lack of macro-scale social security measures.

The Employees’ State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) does provide its members — formal-sector workers who earn below a cut-off — with social security benefits such as medical care and an unemployment allowance under the Atal Beemit Vyakti Kalyan Yojana and the Rajiv Gandhi Shramik Kalyan Yojana.

However, although the ESIC covers about 3.49 crore workers and their families, only 10,728 people claimed and secured the unemployment allowance between 2007 and 2017, Sundar said.

He said this would be a very small fraction of the unemployed ESIC members. He blamed it on “a lack of awareness about the existing ESIC unemployment allowance among its members” and “stringent conditions that make most workers ineligible” for the dole.

Sundar said that under the repealed Industrial Disputes Act, a worker retrenched from a large establishment (one that had over 100 workers) was entitled to a severance allowance worth 15 days’ wages for every year he or she had been employed by that establishment.

But the current Industrial Relations Code exempts establishments with up to 300 workers from this allowance, he said.

“Migrant workers lack the wherewithal to survive after job losses. Whatever savings they had they exhausted during last year’s lockdown. Now they have decided to leave,” Sundar said.

“The state governments are asking them to stay on without any credible assurance about job opportunities.”

Sundar has for several months been suggesting that the government provide money directly into the hands of the poor.

This, he argues, will not only help the working class survive but also sustain demand and consumption, which is necessary for the economy to revive.