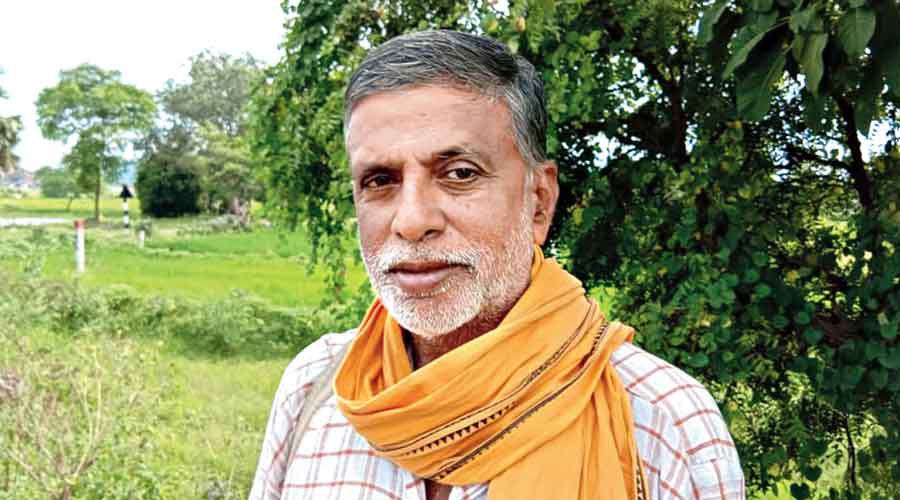

Nimai Ray, an MA in sociology and a farmer, feels the two farm bills that were pushed through in Parliament on Sunday have cost him his independence.

“It’s like your independence has been taken away and you are working as a labourer in some company,” Ray, 56, told The Telegraph on Monday.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has described the passage of the bills as “a watershed moment in the history of Indian agriculture” and the Opposition has labelled them a “death warrant” on the farmer.

But the fears of farmers like Ray, imaginary or otherwise, articulate loud and clear the pitfalls of securing legislative approval without adhering to the basic principles of a parliamentary democracy: proper debate, scrutiny and consultation.

The fears expressed by Ray, who cultivates multiple crops on 12 acres in Jajpur district of Odisha, underscore the importance of transparency, communication and precise drafting while dealing with topics as sensitive as land and food.

“When I got my MA in sociology in 1988, I could have opted for a government or private-sector job, but I decided to live as a farmer. I have worked hard to create my identity as a farmer,” Ray said.

“With the farm bill coming into force, national and international players will come into the picture and we will not be able to hold on to our independent identity. Though there may seem to be some immediate gains for farmers as the market will open up, the bills have long-term repercussions that everyone may not realise at the moment.”

The big fear: The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020, one of the bills cleared on Sunday, allows growers to directly sell their produce to institutional buyers such as big traders and retailers.

Once the bill is signed into law, the farmers can take their produce beyond the premises of what are known as “APMC markets or mandis”.

Under the Agriculture Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Act, a law more than 55 years old, it is compulsory for farmers to take their products to regulated wholesale markets where commission agents help the growers sell their harvest to either the state-run food procurement agency or private traders.

The stated aim of the APMCs is to protect farmers from being exploited by big institutional buyers, but over the years they have become a powerful tool for political parties to control the farm trade.

Many farmer organisations oppose the change that allows big players to buy directly from them, saying it will leave the smaller growers with little bargaining power. Nearly 85 per cent of India’s poor farmers own less than 5 acres, and they find it difficult to directly negotiate with large buyers.

What has deepened the fear is the government’s refusal to categorically state in the bill that the provision of a minimum support price (MSP) would be guaranteed. The Centre has been saying the MSP will be there but “saying” is not the same as incorporating it in the bill in black and white.

A counter-argument has been that once an MSP is set, no private player will pay more than that, and the MSP will become the unofficial “maximum” price or a ceiling that will leave farmers at a disadvantage.

Trust deficit: The bill has been rammed through before a consensus emerged. Besides, what has been unfolding in the past few years has been far from reassuring.

Ray, the farmer, said: “What happened to the hundreds of small grocery shops in urban areas? After big players entered the market, customers started getting things online. They are giving more offers. The small grocery shops started closing down.”

Hypermarkets and e-commerce are still a work in progress in India. While unrealistic discounts offered by the big players have hurt small shops, some traders have gained from the easier availability of wholesale stocks and consumers have enjoyed wider choice. In the lockdown, small groceries thrived while many big stores had to be closed.

Ray added: “One can see the monopolisation in the telecom sector. A similar situation will crop up in the farming sector too. The big companies will enter and take away the farm produce at higher prices. No one will turn up at government mandis to sell their produce. The mandis will be closed down. The farmers will be forced to dance to the tune of the big companies that will dictate the price.”

Contract farming: The second bill, the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020, allows contract farming. Farmers and buyers can enter into agreements before cultivation at a guaranteed price. A dispute settlement mechanism has been prescribed.

On paper, such an arrangement should help the farmer as it removes uncertainties about the demand for the crop, the size and the price.

Trust deficit: But age-old fears, aggravated by a perception that a BJP-friendly oligarchy is being promoted, are a reality.

Ray, the farmer, said: “It will open the door for the conversion of farmers into labourers. We used to cultivate the land of our forefathers. Now, drawn by the lure of money, some farmers may hand over their land to affluent farmers. Later, the big players will take the land and decide what is to be cultivated. Farmers who once owned the land will now work on that land as some or other company’s worker. He will become a labourer in his own land. We don’t want that.”

However, one-third of fruits and vegetables produced in India perish before reaching the food plate. Key among the reasons are the lack of a cold chain infrastructure and an inadequate capacity to process food. The entry of the organised sector with attendant investments may help address some of these issues, leading to more income for the farmers.

States' fear: The grain bowl states of Punjab and Haryana fear that if big institutions start buying directly from the farmers, the state governments will lose out on the tax that these buyers have to pay at wholesale markets.

Political sources say that had the concerns about the MSP and the states’ revenues been addressed, the opposition would not have been so fierce.

The ‘Middlemen’: For decades, some affluent Indians have been justifying their reluctance to pay better prices for farm produce by saying the “middlemen” take the lion’s share, leaving a pittance for the farmer. Political parties too have promoted this theory, blaming every problem on the faceless “middlemen”.

The current controversy has shed light on how commission agents (the “middlemen”) have been discharging useful functions as intermediaries do in most segments where distance separates the producing source and the consumption point.

The government argues that the middlemen at wholesale markets form an extra link in the supply chain, and that their commission pushes up the prices for consumers.

The commission agents help the farmers grade, weigh, pack and sell their harvest to buyers. They also ensure timely payments to the farmers. The agents are also often a source of credit for farmers after droughts or crop failures, or before a daughter’s wedding.

Trust deficit: Some fear that the agents, who form the backbone of the wholesale markets, will be replaced by a set of enforcers on the payroll of the big buyers.

Farmer leaders have said that wholesale markets, which play a crucial role in ensuring timely payments to small farmers, would gradually disappear if large players buy directly from the growers. Without the offer of an alternative arrangement, such as private markets or direct-purchase centres, the new rule does not make any sense, growers have said.

Additional reporting by Reuters