India faces the frightening prospect of tumbling into a recession this fiscal.

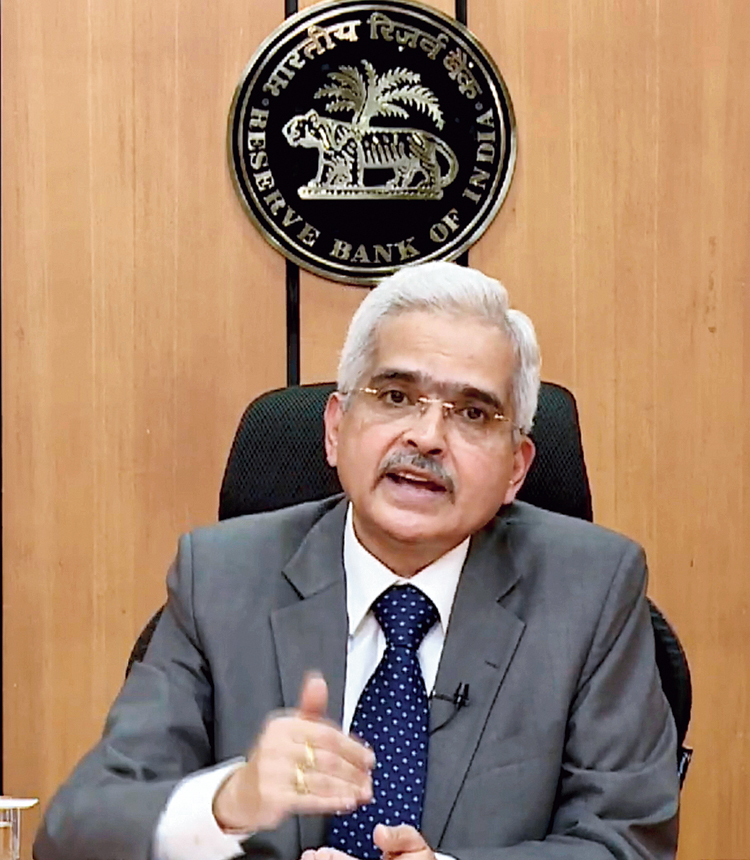

Reserve Bank of India governor Shaktikanta Das on Friday became the first person in officialdom to acknowledge that the coronavirus pandemic could send the economy hurtling into an abyss of despair in tandem with the rest of the global economy which, he said, “is inexorably headed into recession”.

“(India’s) GDP growth in 2020-21 is estimated to remain in negative territory, with some pick-up in growth impulses from the second half of 2020-21 onwards,” the RBI governor said after announcing that the central bank’s policymakers had decided to slash the policy interest rate – the repo – by 40 basis points to 4 per cent, its lowest-ever level.

The monetary policy authorities were forced to step up to the plate once again after finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s five-part, Rs 20.97 lakh crore stimulus package failed to rekindle hopes of an economic recovery following a prolonged pandemic-induced lockdown.

“Once again, central banks have to answer the call to the frontline in defence of the economy,” Das said while trying to reawaken optimism about the future by recalling Mahatma Gandhi’s rallying cry in September 1919: “We may stumble and fall, but shall rise again.”

“Central banks are typically seen as conservative institutions,” Das said. “Yet when the tides turn and all the chips are down, it is to them that the world turns for support.”

The rate cut was announced after an off-cycle meeting of the RBI’s policymakers – the second time they have done so this year. The move may have been prompted by the disappointment over the Modi government’s stimulus, which has triggered accusations from political rivals that the administration is out of touch with reality.

The policy wonks of the central bank were supposed to meet a fortnight later to complete a review of the monetary policy on June 5.

“It is when the horizon is the darkest and human reason is beaten down to the ground that faith shines brightest and comes to our rescue,” Das said at the start of his morning videoconference, which he opened with the calming words that the Mahatma had written in Young India in March 1929.

“Recession” is not a word in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s lexicon – and his government has strenuously asserted that the country will buck the anticipated contraction in the global economy.

Until now, it has only been economists and a handful of foreign brokerages who have predicted that the Indian economy will contract this fiscal because of the disruption in supply and the extremely weak demand.

The RBI governor, who was reading from a prepared statement that voiced a view slightly different from the resolution of the six-member monetary policy committee (MPC), did not use the dreaded R-word. He preferred to use a euphemism – “growth in negative territory” -- and then tried to further soften the blow of his frank words by working in a couple of caveats.

“The end-May 2020 release of the National Statistical Office (NSO) on national income should provide greater clarity, enabling more specific projections of GDP growth in terms of both magnitude and direction. Much will depend on how quickly the Covid curve flattens and begins to moderate,” he said.

“The biggest blow from Covid-19 has been to private consumption, which accounts for about 60 per cent of domestic demand.”

The NSO is supposed to come out with the provisional estimates of national income on May 29. In its second advance estimate, put out on February 28, the NSO had projected GDP growth in 2019-20 at 5 per cent, compared with 6.1 per cent in the previous year.

Global credit rating agencies and brokerages have forecast a recession in India this fiscal and Das’s statement ties in with those stark projections. Goldman Sachs, for instance, recently projected that the real GDP growth in India would contract by 5 per cent this year.

Nuanced statement

While the straight-talking RBI governor did not commit himself to a numerical estimate, the MPC waffled a bit on the growth outlook for the fiscal.

In a slightly more nuanced statement, the MPC said: “Economic activity other than agriculture is likely to remain depressed in the first quarter of 2020-21 in view of the extended lockdown. Even though the lockdown may be lifted by end-May with some restrictions, economic activity even in the second quarter may remain subdued due to social-distancing measures and the temporary shortage of labour.”

It added that a recovery in economic activity was expected to begin in the third quarter and gain momentum in the January-March period of next year as supply lines are gradually restored to normalcy and demand gradually revives.

“For the year as a whole, there is still heightened uncertainty about the duration of the pandemic and how long social-distancing measures are likely to remain in place and, consequently, downside risks to domestic growth remain significant,” the MPC statement said.

“On the other hand, upside impulses could be unleashed if the pandemic is contained, and social-distancing measures are phased out faster.”

It wasn’t immediately clear whether Das was voicing his personal fears of a possible recession while the MPC chose to remain a little more guarded in making such a forecast given the hazy road ahead.

In April, the International Monetary Fund had forecast in its World Economic Outlook that India and China would buck the trend and close this fiscal with positive growth rates of 1.9 per cent and 1.2 per cent, respectively, while the world tipped into a recession with overall global growth tumbling to minus 3 per cent.

The IMF has since expressed concern that the Covid-19 outbreak may trigger a more precipitous slide in global growth, and is expected to come out with an unscheduled reassessment of the April forecast sometime next month.

Earlier this week, IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva had said the fund was likely to revise its forecast for a 3 per cent contraction in the global GDP in 2020 but gave no more details.

Later, in an interview with Reuters, she said data from around the world was worse than expected and “that means it will take us longer to have a full recovery from this crisis”. She added that the IMF would release its new global growth projections in June.

In a sign of things to come, China has broken with a quarter century of tradition and desisted from issuing an economic growth target for 2020 in what is being read as an acknowledgement of the severity of the pandemic’s impact on its economy.

China had reported a 6.1 per cent GDP growth in 2019.