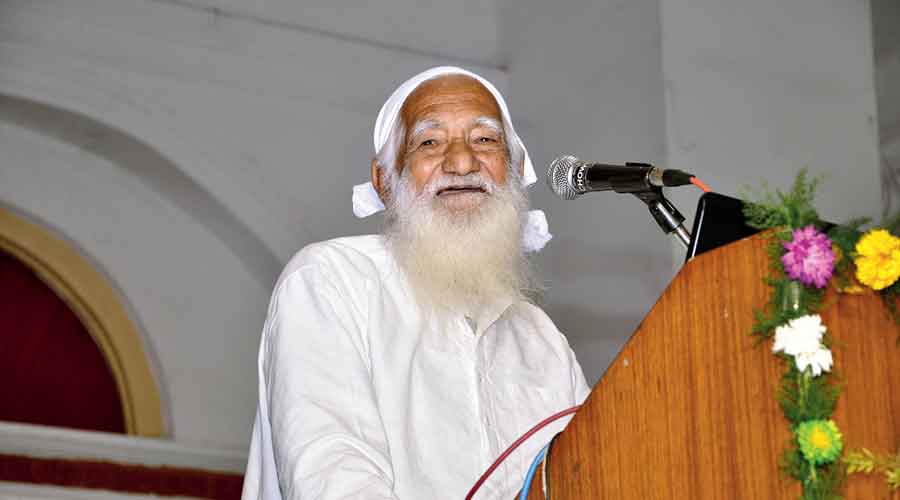

Environmentalist Sundarlal Bahuguna, one of the architects of the Chipko Movement for forest conservation, died on Friday at AIIMS Rishikesh after having caught the coronavirus infection. He was 93.

Bahuguna was best known for his role in the Chipko Movement, a major environmental and social movement that began in 1973 and encouraged local communities to prevent tree felling in the Himalayas, often by embracing the trees. The movement later received the 1987 Right Livelihood Award, often called the “Alternative Nobel Prize”.

Jayanta Bandopadhyay, a retired IIM Calcutta professor and Himalaya expert who had been associated with Bahuguna for more than four decades, recalled his “vision” and hands-on approach.

“Bahugunaji will always be remembered for his strong ecological thinking and its application in the case of the Himalayas, his vision to see the larger picture and zeal to tackle issues first hand and in close association with the community. His wife Vimalaji too played an important role in his initiatives,” Bandopadhyay said.

As part of an early 1980s campaign against the large-scale deforestation of the Himalayas, Bahuguna had undertaken a 5,000km march from Kashmir to Kohima. The initiative led to legislation to protect some areas of the Himalayan forests.

Bahuguna had refused the Padma Shri once in protest against the government’s Himalayan policy.

About a decade ago, when Bahugunaji came to Calcutta for an environmental programme just after receiving the Padma Vibhushan, he had told The Telegraph: “I had earlier refused the Padma Shri. This time I accepted the (Padma Vibhushan) award with the hope that it would give some weightage to my proposal for a detailed Himalayan policy.”

He had added: “Without such a policy, the Himalayas will perish in no time, especially with this persistent change in climate and global warming. I feel the entire Himalayas should be converted into a natural dam with a very aggressive afforestation that will allow the water course to run on its original paths.”

Bahuguna had staunchly opposed the Tehri Dam project in Uttarakhand and defended the right of rivers, including the Ganga, to flow unhindered. He twice staged hunger-strikes to oppose the dam.

“The rivers are affected. I have lived beside the Ganga for six decades and feel that its volume has reduced by half during that period,” he had said.

Referring to climate change, he had warned: “I don’t know the timeline but the glaciers are receding in the mountains faster than earlier.”

Uttarakhand has faced repeated natural disasters, attributed to climate change, in recent years.

Bahuguna had been an active politician in early life and held the post of Uttar Pradesh Congress president, but later left politics to become a social activist whose work bore Gandhi’s influence.

“My wife Vimala, who was a follower of Sarla Behn, Gandhiji’s disciple and a pioneer of women’s empowerment in India, had put to me the condition before marriage that I would have to leave politics and work for social development in the remote villages,” Bahuguna had said.

“I was also influenced by Mira Behn. I left politics and joined the social movement — it was the turning point in my life.”

Bahuguna’s lineage is Bengali — the family were Bandopadhyays. Generations ago, one of his ancestors had moved to Uttar Pradesh from Bengal in search of work and cured a king with his ayurvedic medicines. The grateful king gifted him an area called Bahuguna, and the family over time took on the name of its new estate.

Bahuguna is survived by his wife Vimala Bahuguna, two sons and a daughter.