Fruit seller D. Shabeey of Masapet in Kadapa district of Andhra Pradesh hopes his four children will do some “padha-likha” (reading and writing) work after receiving English education at the government school in the village.

Last month, Shabeey, who is an OBC, gave his consent in favour of English-medium education at the local primary school. “I am a fruit seller. But my children will not do this work. They will certainly do some padha-likha work in life by learning English,” Shabeey told The Telegraph over phone.

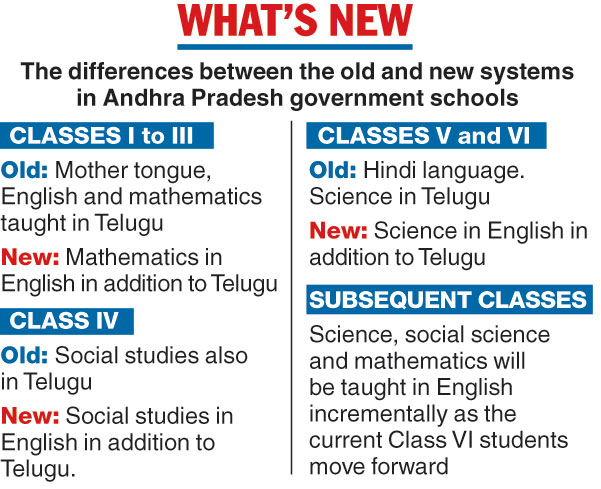

Andhra Pradesh has become the first state in the country to offer English as the medium of education in all its government schools, skirting legal challenges. All 45,000 government schools in the state earlier this month began offering English as the medium of learning, in addition to Telugu, from Class I to VI, a facility that will be extended to Class X over the next four years from the 2021 session.

Telugu used to be the only medium of learning in government schools till the last academic session. Students were offered the option of studying in English only in Classes XI and XII.

Experts have hailed the move as a step to bring about social change, ensure social and economic equality, and dismantle the monopoly of privileged castes and classes in education and jobs.

The government had initially decided that all schools run by it would be turned into English-medium institutions.

However, a case had been filed in Andhra Pradesh High Court challenging this as wrong and violative of the parents’ choice on the medium of instruction for their children.

The petitioners had also alleged that the decision had violated the three-language formula suggested in the National Policy on Education, 1968.

The court had found fault with both sides and struck down the decision. The YSR Congress government led by Jaganmohan Reddy then decided to offer English as an option in addition to Telugu, leaving the choice to the parents. The state government has also moved the Supreme Court against the high court verdict.

Prof. Kancha Ilaiah, a researcher on social justice, recalled how the erstwhile Left Front government in Bengal had deprived a generation of English learning in primary schools in the 1980s, thereby stunting the academic mobility of many.

In Andhra Pradesh, there are 62,000 schools, of which 45,000 are run by the state government, around 15,500 by private managements, while close to 2,000 are private aided, according to data available with the school education department.

Of the 72 lakh children enrolled in Classes I to X, nearly 38 lakh are in government schools.

P.V. Ramesh, senior adviser to the chief minister, said the main draw of the private schools was the medium of instruction being English. About 98.5 per cent of the private schools in Andhra Pradesh are English medium.

“Middle class and lower middle class families are increasingly sending their children to private schools. The government-run schools are essentially serving poor children, those mainly belonging to the Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribe (ST) and OBC communities and some sections of the economically weaker general castes. This is further accentuating the inequality that already exists in society because of caste and class,” Ramesh said.

According to census data, SCs make up 17.08 per cent of Andhra Pradesh’s population, while STs constitute 5.53 per cent. The OBCs constitute 49.5 per cent, as per data on the website of the state’s backward classes welfare department.

Around 19.6 per cent of students enrolled in government schools are SCs, 6.76 per cent are STs and 51.16 are OBCs.

Ramesh said children from English-medium schools were more successful than their Telugu-medium peers in competitive exams such as the Joint Entrance Examination and the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test (NEET).

“English-medium education (in government schools) is an attempt to check the widening social and economic inequalities in society,” Ramesh said.

Ramesh said the changes had to face a lot of opposition. “We have taken the consent of parents on English-medium schooling. Over 96 per cent parents have given their consent. But Telugu medium is being continued for a section of children who have opted for it,” Ramesh said.

Prof. Ilaiah said English-medium education was key to the social and economic progress of children of all section of society.

“Elitism is perpetuated because of the monopoly over English education. Those lacking English education largely do not find any positions in any field of intellectual pursuit. The Andhra Pradesh government’s measure is a step towards demolishing elitism and exclusivity in professions,” Ilaiah said.

He said higher education was also the fief of select castes.

“All states should follow this model. States like Bengal and Tripura, ruled for long by Left parties, did not promote English education. As a result, social inequality is very strong there even today,” Ilaiah said.

S. Rajeev Gandhi, the principal of an upper primary school at Madhireddypalli village in Chittoor district, said the parents of all the 60 students in Classes I to VI had chosen English as the medium of education.

“Parents are very eager to give their children an English education. It is a new experience for all the teachers too,” Gandhi said.

The education department has already made available books in English and has provided training to teachers for the new medium, Ramesh said.

Linguist Panchanan Mohanty, who has served as a faculty member of the Centre of Applied Linguistics and Translation Studies at Hyderabad Central University for over three decades, however, said the Andhra Pradesh government’s decision was not well thought out.

“Mathematics is a universal subject. Teaching mathematics in English is all right. But there is no logic to teach social studies in English. It is about society and culture. Ideally, the mother tongue is best suited for teaching of social studies,” Mohanty said.