The engines of jet planes flying into Delhi swallow on average 6.6 grams of dust on each arrival, the highest among 10 airports assessed worldwide, according to a study that has explored the potential dust factor in accelerated engine wear.

Scientists who set out to quantify the dust doses ingested by jet engines have found

the largest dose at Delhi airport, followed by Niamey airport in Niger and Dubai airport in the United Arab Emirates. More than half the dose comes during the “approach and hold” phase when planes are circling the city, waiting to land.

“The exact dust mass loadings ingested by jet engines had not been quantified previously,” Claire Ryder, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Reading, UK, who led the study, told The Telegraph.

“When dust is sucked into the engines, it melts to form glassy deposits on the blades or hard mineral crusts inside the engines. These crusts disrupt airflow, cause overheating and can result in accelerated engine wear.”

The dust is unlikely to be a safety issue in itself, instead causing engine components to degrade more rapidly, impacting efficiency and maintenance costs, Ryder and her colleagues said in their study, published in the journal Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences.

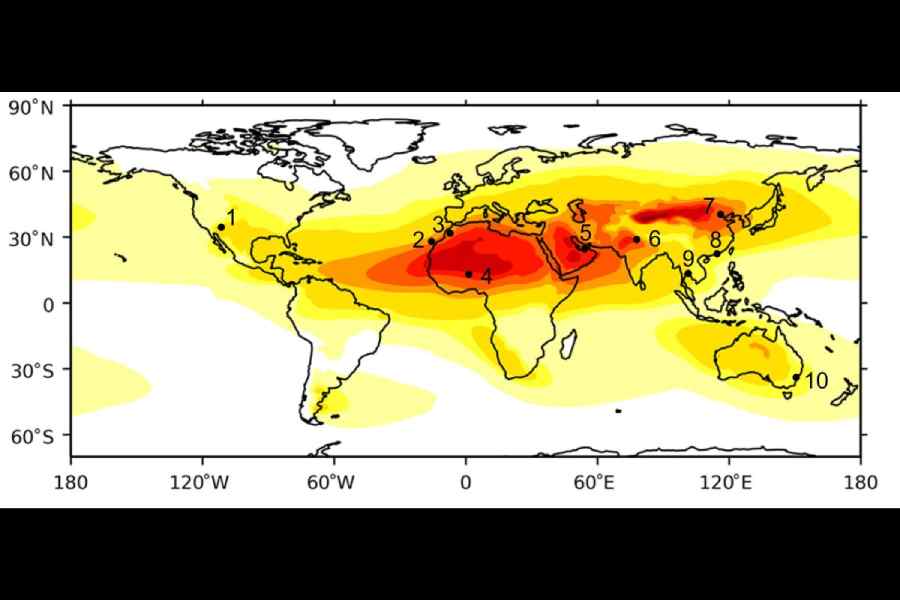

Dust concentrations across the world. Credit: Claire Ryder

“It can mean significant financial costs through maintenance and service (activities) which aircraft manufacturers and airlines are beginning to take into account,” Ryder said.

The findings suggest that airlines and aviation authorities might need to consider options such as increasing the altitudes of aircraft as they await clearance from air traffic controllers to land or adding more night-time flights in dust-prone airports such as Delhi.

The researchers analysed 17 years of atmospheric and satellite data to estimate the dust ingestion by jet engines at 10 airports — Bangkok, Beijing, Canary Islands, Dubai, Hong Kong, Marrakesh, New Delhi, Niamey, Phoenix and Sydney — close to deserts or dust-prone regions.

Their calculations show that flights into Delhi ingest the highest dust load during June-August: 6.6 grams on each descent and 4.4 grams per departure. In Niamey, the largest dose of 4.7 grams per descent occurred in March-May, while Dubai’s peak ingestion of 4.3 grams per descent occurred in June-August.

The quantity of dust ingested on each descent or departure is negligible — ranging from 6.6 grams per descent into Delhi to 0.7 grams per departure from the Canary Islands. But dust can build up over time. An engine that ingests 5 grams per descent and departure would accumulate 10kg dust after 1,000 landings and departures.

Multiple factors --- including proximity to desert sand, wind patterns, soil and atmospheric moisture, and local vegetation cover -- influence natural dust emissions. Dust storms are common across northwest India during the pre-monsoon months.

“These are seasonal phenomena — temperature and pressure changes bring in dust over the region from the Thar desert as well as from deserts over West Asia,” said Rajendra Jenamani, a scientist with the India Meteorological Department who has been head of weather services at Delhi airport.

“Sometimes, the dust can persist, remaining suspended in the atmosphere for days to weeks."

Ryder and her colleagues have proposed two measures to reduce the dust dose. One option would be to change flight schedules to avoid peak dust times. Near-surface dust levels at night can drop to nearly half their peak day-time levels.

The second would be to raise the altitudes at which planes circle while waiting to land from the typical 1km. For most airports, dust concentrations decrease above 1km altitude.

Raising the holding altitude from 1km to 3km during the peak dust concentration months of June-August would reduce the ingested dust dose by 75 per cent in Delhi and 63 per cent in Dubai, the researchers have said.