The Indian economy shrank by 23.9 per cent in the first quarter ended June 30, signalling that the road to recovery would be more arduous than most economists have projected.

It marks the steepest decline since the National Statistical Office (NSO) started quarterly measurement of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1996.

The slide in real GDP — which is measured on the basis of prices in 2011-12 — had been expected after the Narendra Modi government clamped the world’s severest lockdown in March to stop the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, triggering a slump in consumer spending, private investment and exports.

But the fall has been steeper than forecast. The contraction in India’s economic growth during April-June has been amongst the severest so far globally. Only Peru (-30.2 per cent) and Macau (-67.8 per cent) have reported lower GDP growth numbers for the period, Care Ratings said in a research report.

Real GDP is widely expected to contract this year with estimates ranging from the IMF’s 4.9 per cent slide to the OECD’s worst-case estimate of a 7.3 per cent fall in the eventuality of a second outbreak of the pandemic in October-November. Other economists have come out with more depressing forecasts. Most credit rating agencies have already spooked the market with forecasts of a real GDP contraction ranging from 15 to 25 per cent.

The last time that India faced a full-year contraction in its real GDP was in 1980.

But the more worrying fact is that nominal GDP has also contracted by 22.6 per cent and presages the possibility that the overall size of the Indian economy could shrink this fiscal — a frightening prospect that the country has never had to deal with.

The main difference between nominal GDP and real GDP is the adjustment for inflation. Since nominal GDP is calculated using current prices, it does not require any adjustments for inflation.

Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had articulated these fears a few weeks ago when he said that a growing consensus had started to emerge among economists that nominal GDP could also contract this year.

“If it happens, it will be the first time in independent India. I hope the consensus is wrong,” Singh had said.

Last year, real GDP had grown by 5.2 per cent in the first quarter and the nominal GDP by 8.1 per cent.

A contraction in the nominal GDP will have big implications for tax collections this year, deepen job losses, spark wage cuts, depress demand, trammel production processes and lead to a ballooning fiscal deficit that will then need to be papered over by greater borrowings.

In May, the Centre had jacked up its gross borrowing programme by 53 per cent to Rs 12 lakh crore from a budgeted Rs 7.8 lakh crore.

Data show that of the 54 countries that have reported their GDP figures for the April-June quarter, only China and Vietnam have recorded a positive growth over the same period last year.

China’s economy grew by 3.2 per cent in April-June after recording a decline of 6.8 per cent in January-March 2020.

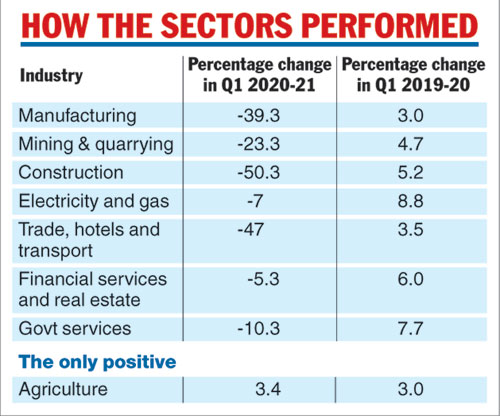

Sectors battered

Manufacturing — which accounts for 13.8 per cent of the gross value added (GVA) at basic prices in the first quarter and serves as a nerve centre for job creation — contracted by a sharp 39.3 per cent. The construction sector shrank by 50.3 per cent while mining output fell by 23.3 per cent.

Agriculture was the sole bright spot and grew 3.4 per cent.

The NSO note said: “The quarterly GVA at Constant (2011-12) prices for the first quarter of 2020-21 is estimated at Rs 25.53 lakh crore, as against Rs 33.08 lakh crore in Q1 of 2019-20, showing a contraction of 22.8 per cent.”

The GVA is a key metric to measure economic activity that strips out the impact of taxes and subsidies on the value of output.

Congress leader and former finance minister P. Chidambaram said: “The only sector that has grown is agriculture, forestry and fishing at 3.4 per cent. The finance minister (Nirmala Sitharaman), who blamed an ‘Act of God’ for the economic decline, should be grateful to the farmers and the gods who blessed the farmers.”

Sitharaman has been castigated after she termed the Covid-19 pandemic an act of God — and refused to compensate states for any loss of revenues on account of falling goods and services tax (GST) collections and a virtually empty compensation cess corpus.

Krishnamurthy Subramanian, chief economist at the finance ministry, said the Indian economy was set for a “V-shaped” recovery and should perform better in the coming quarters as indicated by a pickup in rail freight, power consumption and tax collections.

Very few economists support that view and even the Reserve Bank of India has indicated that the economy will contract this year while refusing to put out a numerical estimate.

Consumer spending — the main driver of the economy — dropped by 24.5 per cent at current prices while capital investments were down by 47.9 per cent.

Exports were down by 17.1 per cent in the first quarter at Rs 7,68,037 crore while imports shrank by 38.5 per cent to Rs 6,89,734 crore at current prices.

M. Govinda Rao, a member of the 14th finance commission and currently chief economic adviser at Brickwork Ratings, said: “The economy has certainly entered a recession phase as the second quarter GDP number is also most likely going to be negative. However, the pace of contraction may be slower in Q2 than in Q1 due to the lower base, which will wane to some extent, and the gradual lifting of the lockdown in areas and sectors, which is likely to improve economic activity.”

D.K. Srivastava, chief policy adviser at EY India, said: “The first-quarter numbers highlight an extremely challenging outlook for the Indian economy with only one sector — agriculture — showing positive growth. Signals are strong that FY21 is likely to end in a net contraction. With nominal GDP also showing a negative growth of about (-)23 per cent in 1QFY21, tax revenues are also likely to contract sharply in the year as a whole. The Indian economy has clearly landed in a severe vicious cycle with the need to stimulate demand becoming paramount while the capacity to support demand by the government is at its weakest. Without stimulating private consumption and investment demand, it may be difficult to arrest this downward momentum.”

The NSO said its data collection mechanism had been badly hampered by the lockdown restrictions and the severity of the resultant impact on economic activity.

“In these circumstances, the usual data sources were substituted by alternatives like GST, interactions with professional bodies, etc. and which were clearly limited,” it said.