The Reserve Bank of India’s policymakers shocked economists, industry and the Street by deciding to hit the pause button on interest rate cuts after five downward revisions this year.

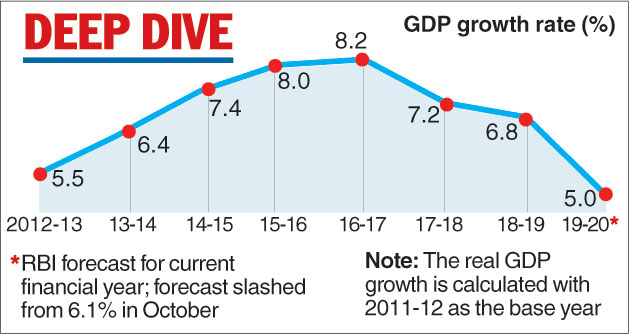

The six-member monetary policy committee (MPC) of the central bank also slashed its growth forecast for this financial year to 5 per cent from 6.1 per cent at the October meeting.

The decision to retain the policy rate — the repo — at 5.15 per cent was unanimous and indicated that the central bank was peeved about being second-guessed on its monetary policy moves and had worked up the nerve to resist popular pressure to cut rates once again.

It has sent out the strongest signal yet that the burden of reviving the economy through counter-cyclical measures now rests squarely on the Narendra Modi government’s shoulders.

“We decided that we could no longer mechanically cut interest rates,” RBI governor Shaktikanta Das told reporters in a post-policy interaction while conceding there was room for future rate cuts that would depend on emerging data streams and clarity on the government’s fiscal announcements in next year’s budget.

“The timing of the rate cut is very important to optimise its impact. You must cut when the impact is the maximum,” Das said.

Since February, the RBI has cut the repo rate by 135 basis points. But the commercial banks have brought down the weighted average lending rate on fresh rupee loans by only 44 basis points. “The full impact of our policy rate cuts is still playing out. We should allow more time for this to be reflected in bank lending rates,” the RBI governor said.

“Let us keep in mind the fact that inflation targeting is the prime objective of the central bank. The RBI is also required to keep in mind the objective of growth; that has been given due weightage and the MPC has given a very clear and unambiguous forward guidance that there is space for further rate cuts and the RBI will act if the evolving situation so warrants,” Das added.

The decision to focus on the task of taming inflation at a time when second quarter growth sank to a 26- quarter low of 4.5 per cent is surprising since the RBI has often spoken about the need to crank up growth -- and has in fact adopted an accommodative stance by pumping liquidity into the system.

The RBI decision puts the ball firmly in the court of the government, and finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman will have to devise a coherent strategy to haul the economy out of the morass.

In a way, the central bank is also admitting that the staccato rate cuts since February have not had the desired impact on growth.

The next monetary policy review meeting will be held from February 4 to 6 -- after the Union budget for 2020-21 -- which means that there is unlikely to be another rate cut until the government announces its next set of fiscal measures.

Governor Das said the policymakers were concerned about the upside risks to inflation. Retail inflation rose to 4.62 per cent in October, largely driven by the surge in vegetable prices which, the RBI reckons, may soften by early February.

However, the central bank said it had started to see price pressures building up in milk, pulses and sugar which could sustain the upward trajectory of food inflation.

The RBI said while core inflation (which strips out the effect of food and fuel items) was within the comfort zone of less than 4 per cent, the recent increase in telecom tariffs could pose some upside risks.

The central bank raised its inflation forecast for the second half (October 2019-March 2020) to a range of 4.7 to 5.1 per cent -- well above its comfort level of 4 per cent -- and said it did not see possibility of price rise in the economy moderating until the second quarter of the next fiscal when it might tumble to 3.8 per cent.

The RBI’s shock decision to hold rates forced several analysts to reconsider their own forecasts on the pace of rate cuts.

“There is a possibility that the RBI might stay on hold even at its next policy meeting in February,” said Abheek Barua, chief economist at HDFC Bank. “If fiscal policy is expansionary in the upcoming budget and provides some support for growth, the RBI could further be convinced to hold back rate cuts.”

Others were perplexed by the “underwhelming response” of the RBI.

“There has been a 3-4 per cent fall in nominal GDP over a little more than a year and a half,' says Suyash Choudhary of IDFC Mutual Fund, who believes that the Centre will need to grapple with the fact that India has run out of savings to be able to fund a robust counter-cyclical fiscal stimulus.

“It is evident (at least to us) that there is a greater role for monetary policy here,” he added.