An ayurveda professor from a top medical school has urged regulatory authorities to drop incorrect and obsolete concepts from the ayurveda curriculum and subject its principles to scientific scrutiny.

Some ayurveda practitioners and modern doctors have applauded the call for change from an “insider”.

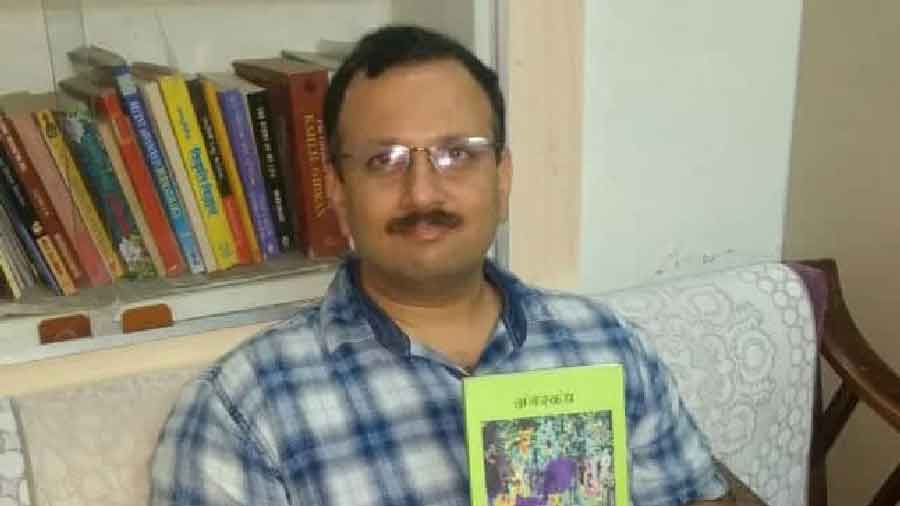

Kishor Patwardhan, professor of physiology in the ayurveda faculty at the Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, has said that ayurveda students deserve to be taught modern anatomy and physiology undiluted by inaccuracies from ancient ayurvedic texts.

“Understanding the biological basis of disease is essential for any physician, irrespective of the stream,” Patwardhan said in a reflective commentary, “Confessions of an ayurveda professor”, in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics (IJME).

In the commentary, Patwardhan said he had himself for years, while teaching, attempted “laborious reinterpretation” of inaccurate content to legitimise ancient ayurveda literature alongside advances in modern physiology.

We assume that our texts are ever-relevant and irrefutable. Most of our research starts with the premise that these theories are true and unquestionable

Kishor Patwardhan

He said that among “the most disturbing” of such erroneous concepts was the idea in ancient ayurveda textbooks that semen was produced in the bone marrow and circulated throughout the body.

Patwardhan said that since modern medicine had established the reproductive tract as the source of semen, he had tried to reinterpret the word for bone marrow in ayurvedic literature and argue that ancient text writers had used the word broadly for other tissues as well.

Ayurveda texts also say that the liver and the spleen impart the red colour to blood. Using knowledge from modern physiology that the liver and the spleen help with the formation of red blood cells in embryonic life, Patwardhan said, it could be argued erroneously that they were important organs in blood formation in adult life. In reality, blood cells are produced in the bone marrow after birth.

“We assume that our texts are ever-relevant and irrefutable. Most of our research starts with the premise that these theories are true and unquestionable,” Patwardhan wrote, proposing steps to identify the content in the existing ayurveda curriculum that can be “safely dropped”.

Some practitioners of ayurveda and modern medicine have described Patwardhan’s commentary as a much-needed appeal for changes to the current curriculum taught in ayurveda colleges. They say the regulatory authorities for traditional Indian medicine have so far resisted these changes.

Over 25,000 students graduate each year with BAMS (Bachelor of Ayurveda Medicine and Surgery) degrees from over 400 colleges across India. In several states, ayurveda graduates work alongside modern medicine practitioners, rendering health care in public and private facilities.

Ayurveda practitioners said that 60 per cent of the current ayurveda curriculum for physiology involved ayurveda concepts and the remaining 40 per cent drew on modern physiology. For anatomy, the split was 50-50.

“Mismatches in the syllabus could leave students bewildered. One lesson wrongly says that semen is produced in the bone marrow, another lesson says semen is produced in the reproductive tract,” said G.L. Krishna, an ayurveda practitioner in Bangalore who, too, has been calling for curriculum revisions.

Krishna said the resistance to change probably emerges from a belief in the “immortality” of ancient texts.

“It is encouraging that Dr Patwardhan has called for change,” Krishna told The Telegraph. Patwardhan has played a role in guiding curriculum development but has faced resistance from colleagues to initiating the changes he has sought. “If a dozen such senior faculty members do this, it’ll get the momentum it deserves,” Krishna said.

Sreenivasa Prasad Buduru, president of the board of ayurveda in the National Commission for Indian Systems of Medicine, the regulatory body overseeing traditional medicine, said moves to change the curriculum had already been initiated.

“It has started — we’ll do it in phases as new batches come in,” Buduru said.

Amar Jesani, a modern physician and IJME editor, said the journal had published Patwardhan’s commentary because “we saw great potential to initiate debate on the approach we should adopt towards ayurveda”.

“The Centre has accorded great importance to the traditional systems of medicine. Patwardhan has proposed a way to advance and further develop ayurveda, incorporating modern knowledge. Others may have alternative suggestions,” Jesani said.

Sunil Pandya, a neurosurgeon at Jaslok Hospital, Mumbai, said the commentary underlined that like students of modern medicine, ayurveda students deserved access to the latest scientific advances. Patwardhan’s approach should be adopted for all the ayurveda subjects, he said.

“While gold must be retained, dross must be discarded ruthlessly without allowing disabling sentiment to interfere,” Pandya wrote in the same journal last Sunday in a response to the commentary.