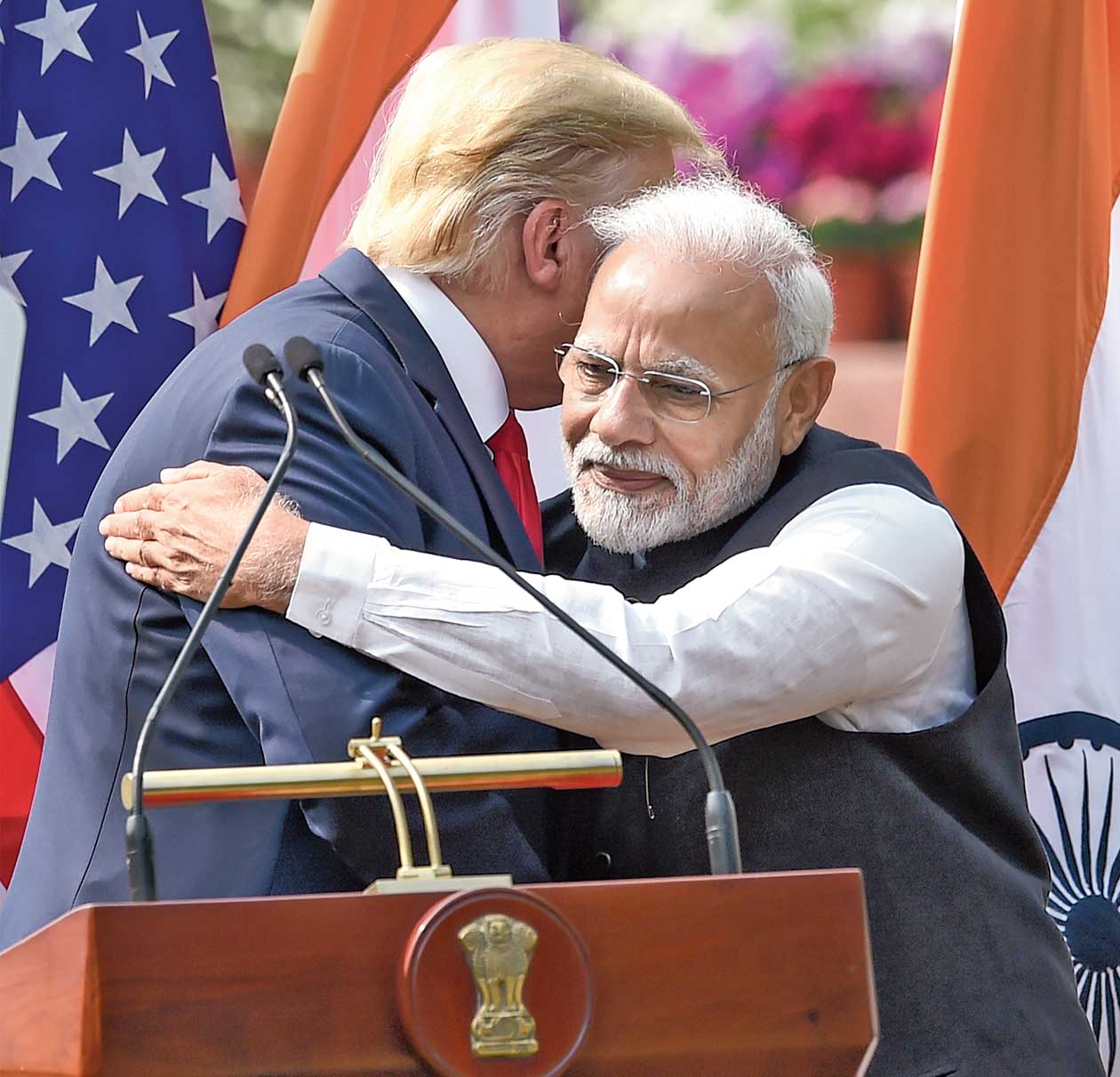

President Donald Trump clinched a $3-billion defence deal with the Narendra Modi government and extracted promises of billions of dollars of investments from Indian industrialists but the “big trade deal” that would have sealed the success of his first state visit to India proved to be elusive.

The two sides have agreed to pursue a comprehensive trade agreement but there is little likelihood of signing it before the US presidential election scheduled for November 3.

One of the major sticking points is over the high tariffs that India imposes on a class of goods that American industry is keen to export. These include dairy products, medical devices and Harley-Davidson motorcycles.

Negotiations between the two countries over India’s tariff reductions have been deadlocked since 2018, prompting Trump to retaliate by slapping duties on steel and aluminium in March 2018. In May last year, he ratcheted up pressure on Delhi by refusing to extend duty benefits under the generalised system of preferences on a range of products like artificial jewellery, engineering goods, building materials, pharmaceuticals, chemicals and leather goods.

Trump kept up the refrain on Tuesday.

“India is probably the highest tariff nation in the world…. We have to stop that…. I think we are beginning to understand each other,” he said.

“Harley-Davidson has to pay tremendous tariffs in India. When India sends motorcycles to the US, there are virtually no tariffs. For the most part, there are absolutely no tariffs. I just said that is unfair and we are working it out,” he added.

India currently levies a 50 per cent import duty on some Harley-Davidson motorcycle models.

Harley-Davidson, the Wisconsin-based motorcycle maker, has a plant in India that assembles bikes from components sourced from its US facilities.

Critics have said that Trump has been pushing for lower tariffs on Harley-Davidson bikes because he wants to make a grand, symbolic gesture ahead of the US presidential elections in a crucial swing state that he barely won the last time.

Wisconsin is also home to America’s dairy industry and President Trump has been trying hard to persuade India to buy dairy products including milk from the US to slake its ever-growing demand.

India is the world’s largest milk producer but isn’t keen to import milk from the US that could threaten the livelihood of its small dairy cooperatives, most of which have flourished in Modi’s home state Gujarat.

The American side was left aghast at India’s stand that it was ready to import milk from the US only if it came from cows that had been kept on a strict vegetarian diet — a ruse it believed the Modi government had thought up to scupper any agreement.

The US side’s offer to put the American cows — which are accustomed to animal feed — on a 90-day vegetarian diet before their milk was sent to India was also shot down.

The US has also been furious over the Modi government’s sudden decision to raise import duties in its recent budget on walnuts, medical devices, cheese and electronics goods — for all of which it is seeking market access in India.

“An FTA (free trade agreement) between India and US would have wide ranging ramifications for the domestic industries, and a clear cost benefit analysis would be needed to gauge its total impact,” said the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and the US India Business Council (USIBC) in a report titled $500 Billion Roadmap for bilateral trade and business.

India seems more keen to work first towards a limited trade deal with the US before going for a big-bang free trade agreement.

“We will hopefully close the first end of the limited engagement that we have already discussed and nearly finalised,” commerce minister Piyush Goyal said at an industry event. “But I am delighted that both the leaders have decided to formally engage to move towards a Free Trade Agreement between these two big economies.”

After India baulked on a full-scale trade deal, US trade representative Robert Lighthizer dropped out of the Trump delegation to India.

Goyal insisted that the two sides would be able to wrap up a larger trade deal pretty quickly because both were “transparent economies” with a high degree of trust in each other.

“So, I certainly do not see a situation where the free trade negotiations will drag on for years,” he added.

Not everyone shares that view.

“The government needs to stop making contradictory policy statements. On the one hand, we are taking steps to protect the domestic industry through the Make in India programme. On the other, the government is saying that it is open to a free trade agreement with the US that would cover sensitive areas like agriculture, medical equipment, the dairy sector and intellectual property rights,” said Biswajit Dhar of Jawaharlal Nehru University.

“We cannot have it both ways,” he added.

In 2018-19, India’s exports to the US stood at $52.4 billion, while imports amounted to $35.5 billion.

India enjoyed a trade surplus of $16.9 billion last year — down from $21.3 billion in 2017-18 — as a result of the US trade action.

At the same time, India also received foreign direct investment (FDI) worth $3.13 billion from the US in 2018-19, higher than $2 billion in 2017-18.