Prince Mukarram Jah’s life was possibly the ultimate example of the brutal truth that great wealth is no guarantee of happiness. His grandfather, the seventh Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan, was splashed on the cover of Time magazine in 1937 that described him as the world’s richest man. (He was so wealthy that he was said to have used the 184-carat Jacob diamond as a paperweight). After Hyderabad became part of India in 1948, the family’s fortunes began a dramatic reversal.

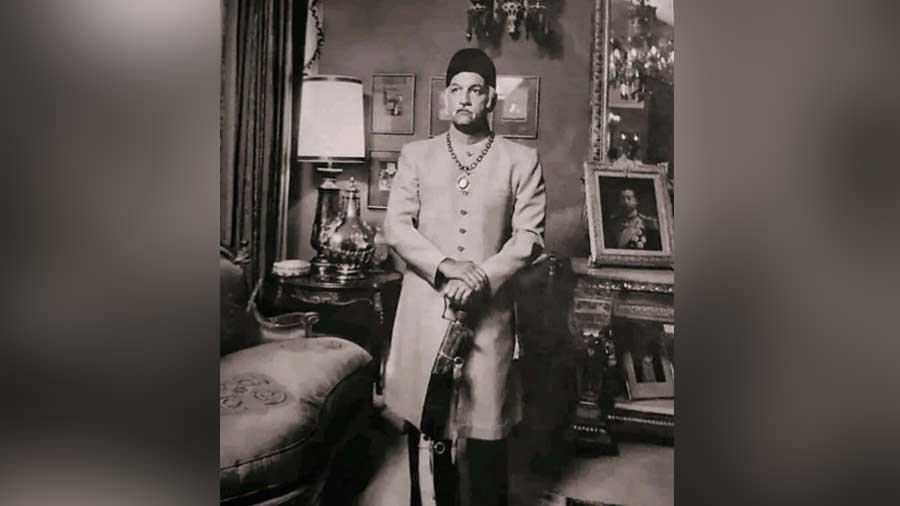

Still, when Mukarram, the eighth and last Nizam of Hyderabad, ascended to the throne in 1967, he inherited a fortune that included palaces and priceless Mughal art and antiques as well as gold, silver and jewels that made him India’s richest man.

But in 1971, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi abolished privy purses and abolished the Nizam’s title. The government also imposed crippling new wealth taxes.

By the time, Mukarram died in Istanbul on Saturday at the age of 89, what had once been the world’s greatest fortune had been largely lost – sold, looted or squandered.

Family members have been fighting in the courts to win access to what’s left.

Mukarram, who was named as his grandfather’s heir in preference to any of his children, proved unequal to the task of managing the unwieldy “empire” he had inherited of ramshackle palaces and an enormous entourage of avaricious retainers and financial claims by several thousand descendants of different Nizams.

Perhaps it was always to be an impossible task – Osman Ali Khan had dozens of concubines and a reputed 149 children, 34 of whom were legitimate. Inevitably, they all laid claims to the estate and clamoured for large allowances.

Mukarram, who was born in Nice and educated at Doon School in Dehradun and later at Harrow, Cambridge and Sandhurst in Britain, had no head for business. He was indifferent to his title. “Officially I was the Nizam, but since 1948 there was nothing to rule over,” he told Australian author John Zubrzycki who wrote a biography of Mukarram in 2006.

After a whirlwind romance in London in 1959, he married Princess Esra, who was from well-to-do Turkish liberal family aristocratic and had studied architecture. They had two children, Azmet and Shehkyar.

But Mukarram found himself battling a myriad of legal battles and avaricious retainers and famously abandoned the worse-than-Byzantine tangles to settle on a 200,000-acre sheep farm in Australia outside Perth where he was said to have been happiest driving bulldozers and tinkering with automobiles and even an amphibious battle tank he kept near his home. 'At Cambridge I got my master of arts, majoring in literature,' he told an Australian interviewer. 'Yet now I can't remember if literature has one or two Ts.'

Mukarram separated from Princess Esra in 1973 (she had no desire to relocate to the Australian bush) and brusquely informed his son who was studying in London that he and his sister Shehkyar could never return to Hyderabad. Said Azmet to The Telegraph in an interview: “We were told we could never come back to India and Hyderabad, so we switched to being Turkish and British.” His father finally reconciled with the children 20 years later.

Mukarram delighted in living in the dusty Australian outback. “I love this place, miles and miles of open country, and not a bloody Indian in sight,” Time magazine quoted him as saying. But he encountered more financial difficulties – and tragedy – in Australia while back in Hyderabad his properties were looted or sold for a song by unscrupulous administrators and friends whom he had tasked with managing his holdings.

In Australia, he married an Australian woman Helen Simmons. Helen died of AIDS caught from a lover. They had two sons Prince Alexander Azam Jah and Umar who died of a drug overdose.

Prince Azam is extremely close to Princess Esra and said about her: “After my brother passed away, she took me under her wing and stood by me like a rock. I love Princess Esra with all my heart. She has been a mother to me when she needn't have been.” Azam will be returning to Hyderabad with Esra, Azmet and Shehkyar for Mukarram's funeral.

Mukarram invested millions of dollars buying equipment for the sheep farm which never made a profit, then invested millions more in buying a dud gold mine, buying a Perth mansion and converting a minesweeper into a giant luxury yacht.

Finally, after 20 years in Australia, he moved to Turkey in 1996 to escape his creditors. He spent the last three decades living the life of a recluse in a small two-bedroom flat in the south of Turkey.

Mukarram had strong ties to Turkey as his mother was the Ottoman caliph’s daughter though he always said the years he spent in the wide-open spaces of Australia were his happiest. “To Jah’s ears there was nothing more poetic than the drone of a diesel engine,” said his biographer. Mukarram dressed like his Outback neighbours and delighted in being mistaken for a farm worker.

Mukarram's third wife Manolya Onur, a former Miss Turkey, and her daughter Niloufer also lived in Hyderabad for some years, Manolya died in 2017 but she had been estranged from her ex-husband and his other families. For many years she was embroiled in legal battles for property she says was promised to her daughter. Mukarram in the end married five times.

As his financial problems mounted, he turned in 1996 to his indomitable first wife Princess Esra to restore his crumbling palaces and fortunes. It was a smart decision. Esra says she was terrified by the huge responsibility that had been placed on her shoulders but she worked with the Taj Group to restore the Falaknuma Palace which is now one of the group’s most prized palace hotels. It had been locked up and in a state of crumbling disrepair for decades. Now even the table where Osman Ali Khan worked -- and on which he placed the Jacob’s Diamond which was used as a paperweight – are smartly back in place. The table that is. Not the diamond.

Esra said she kept a close eye on all the changes that had to be made during the nearly decade-long restoration process. “We worked on every detail. We had to do things like the lighting and the air-conditioning without ruining the place. I worked with them like a worker, shifting furniture and everything.” She also called in Intach founder Martand Singh and architect Rahul Mehrotra to assist with the renovation of the Chowmahalla Palace, the city’s principle palace. She also enlisted legal help to settle claims of many of the descendants of the Nizams.

Azmet, Mukarram’s first-born son, said in a 2014 interview with The Telegraph that his father was guiding all the restoration work from his base in Turkey. “My mother supervised everything. But my father is in the background, financing everything. This is a family endeavour. My mother has also really pushed the envelope.”

Exactly how rich – or poor -- was Mukarram Jah? That’s tough to estimate but keep in mind that in 1995 the government paid Rs 218 crore and acquired the Nizam’s jewellery collection – though an international auction house once reckoned it was worth well over Rs 1,000 crore.

Experts say it’s tough to place a value on the antique collection as many pieces are unique. For decades the collection was in the vaults of the Hong Kong Bank and it’s now in a Reserve Bank strongroom. Around 173 pieces from the jewellery collection were put on show in Delhi a few years ago.

It was said that Osman Ali Khan had trucks filled with gold ingots and pearls that were too numerous to count. But Mukarram Jah was reputed to be extremely profligate and deeply in debt for large chunks of his life. He’s said to have sold most of the land and property that he owned around the world to pay off debts. Then, dramatically, there was the POUNDS 1 million deposited in the NatWest Bank in 1948 by a Hyderabad envoy in London with instructions that it should belong to the Pakistan government. India contested this and finally won the case in 2019. The money was divided between the government and the Nizam.

Among the treasures recovered in recent years were two vintage cars – an early 1900s Rolls Royce Silver Ghost that had once been used as a state limousine by Osman Ali Khan and a 1906-model Napier L76. Both vehicles have won numerous awards since they were restored.

Could it all have been different? For that we should go back all the way to the 1940s when Osman Ali Khan tried to buy Mormugao port from the Portuguese. If his landlocked kingdom had a route to the sea, he calculated he had a greater chance of staying independent or joining Pakistan. In the event, Hyderabad was only able to hold out against the Indian Army for 100 hours.

Mukarram Jah inherited great riches but it was a crumbling legacy. Given his lack of business acumen, there seems little possibility he could have turned the situation around. “He was philosophical about how ‘kismet’ or fate had guided his life,” Zubrzycki said.

In recent years, Mukarram suffered from diabetes-related illnesses. His body is being flown back from Istanbul and the Telangana government is giving him a full state funeral after which he will be interred in the Asaf Jahi family tombs. His body will first lie in state in the Chowmahalla Palace.