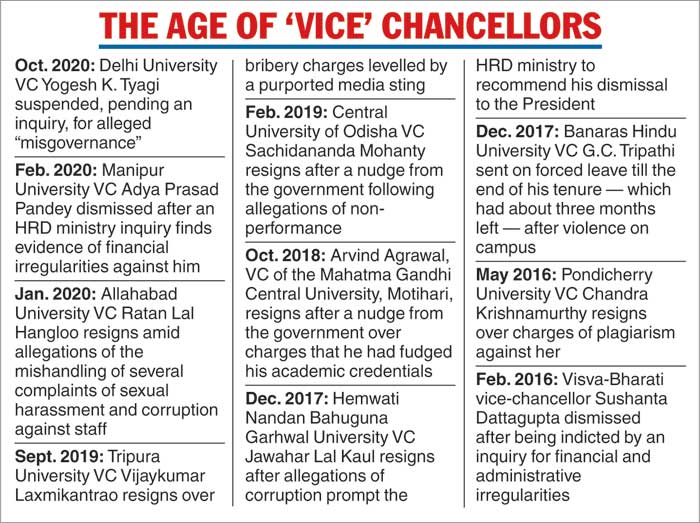

Delhi University vice-chancellor Yogesh K. Tyagi’s suspension for “misgovernance” this week makes him the 10th VC of a central university in less than five years to be suspended, dismissed, forced to resign or sent on punishment leave till the end of their tenure.

The trend, fuelled by charges of corruption or inefficiency against the VCs, has prompted several academics to question the quality of academic leaders being appointed in recent years and flag the flaws in the government’s manner of selecting them.

The critics clarified that they were not fingering individual VCs but were concerned that the large number of VCs having to leave over allegations of impropriety or incompetence reflected poorly on the selection process. (See chart)

In comparison, only one central university VC had resigned amid charges of impropriety during the 10 years of UPA rule.

In January 2011, Rajiv Gandhi University vice-chancellor K.C. Belliappa had quit after a fact-finding committee indicted him on the charge of sending a lewd email to a senior teacher.

However, two of the 10 VCs who have left under a cloud since 2016 — Visva-Bharati vice-chancellor Sushanta Dattagupta and Pondicherry University VC Chandra Krishnamurthy — had been appointed by the UPA government.

“There’s no problem with the (set) procedure (for selection of VCs), but the procedure is violated at every level,” sociologist Andre Beteille told The Telegraph. “Those who are very good teachers or researchers do not want to become VCs. The selection of VCs is marked by political influence at every level,” he added.

Padmanabhan Balaram, former director of IISc Bangalore, agreed with Beteille that the problem was less with the selection rules than with their (lack of) implementation.

He said the government’s political bias came into play at every step of the appointment process, from picking the selection panel to short-listing the candidates.

“Selecting the selectors is very important. Not much attention is paid to this. It’s because governments want to control institutions or satisfy certain people. Any policy is meaningless if you have no commitment to implement it,” Balaram said.

Such wielding of political influence in the selection of academic heads was always there but “it has deteriorated in recent years”, Balaram said.

He said similar use of political clout by state governments marked the selection of VCs of state universities too.

Aswini K. Mohapatra, dean of the School of International Studies at JNU, however, said the set procedure for selecting VCs and other academic heads was itself flawed.

He said the government should introduce clear-cut parameters to help the selection panels assess the candidates’ leadership skills.

Mohapatra said that beyond setting an eligibility criterion of 10 years’ experience as a professor for the candidates, the current rules give a free hand to the selection panels, whose interviewers tend to focus on the applicants’ academic credentials while ignoring their record as administrators.

“Merely 10 years of professorship and some administrative experience should not be taken as proof of a person’s leadership abilities. The committee should look at what the person has done in his previous postings,” he said.

One example of an academic with a questionable record being appointed vice-chancellor and then being rewarded with an extension despite a controversial tenure is provided by Appa Rao Podile, appointed as VC of Hyderabad Central University in 2015.

It was during his tenure that Rohith Vemula, suspended from the hostel with four other Dalit scholars following complaints of assault lodged by the ABVP, hanged himself in January 2016.

When the suicide brought a bad name to the Union HRD ministry, which had written five letters to the university seeking action against Vemula and his group, Podile was sent on forced leave. He rejoined office in March 2016 on “popular demand” and was exonerated by a judicial commission.

However, in April 2016, Podile admitted to plagiarism in three papers he had co-authored between 2007 and 2014. In September 2020, after he had completed his five-year tenure, he was given a year’s extension by the President on the advice of the government.

There have been allegations that some vice-chancellors accepted bribes for university appointments and contracts.

US example

Balaram said the best way of insulating the selection process from political bias would be to end the government’s role in it altogether.

He cited how, at top foreign institutions like Harvard University or the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the boards of trustees or overseers — made up of eminent people who receive no pay — set up the selection panel without government interference.

Nor do America’s state or federal governments take any part in the appointment of the board members, who are selected by the existing board members.

In India, the government not only appoints the members of the public universities’ boards of governors, executive councils or syndicates but also helps pick the selection panel and vets its recommendations.

“In the US, the boards of trustees operate independently but the governing bodies in India are not free from influence. So you see the institutions crumbling in several respects,” Balaram said.

For instance, the education (formerly HRD) minister heads the interview panels that select the IIT directors — a practice begun by Kapil Sibal in 2011.

Balaram had last year headed a committee that the UGC had appointed to suggest ways of improving the quality of research in the universities. Among the panel’s recommendations was to drop the HRD minister as head of the interview panel. The recommendation is yet to be accepted, a government official said.

But does the trend of dismissals and forced resignations imply that the government, even if its selection practices are faulty, remains ever alert to the possibility of rectification?

Several academics laughed off the suggestion, saying that questionable selections are dime a dozen but the government acts only in a few cases — mostly out of political motives.

“For example, the government acted against the Delhi University VC at the fag end of his tenure despite the problem of delayed appointments persisting for a long time,” Balram said.

“Had the VC not had a spat with some members of the university administration, he would have completed his tenure successfully.”

A retired JNU professor who asked not to be quoted said that only when a VC refuses to toe its diktats beyond a point does the government build up a case to get rid of him.

“The government appoints only those who are committed to, or claim to be committed to, its ideology. In recent years, the practice has been to hand over the names of favoured candidates to the search panels,” the veteran academic said.

“Even after selection and appointment, some of them fail to follow the road map chalked out for them --- to appoint only RSS sympathisers as teachers and target teachers’ and students’ bodies that differ from their ideology. Such VCs face action.”