It’s straight out of President Donald Trump’s trade war playbook. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s furious with the Malaysians and he’s hitting back by stopping the import of palm oil, the key commodity that India buys from the South East Asian nation. But using trade as a weapon always has its price, especially when the government’s fighting rising food prices and trying to tame inflation riding at a six-year high.

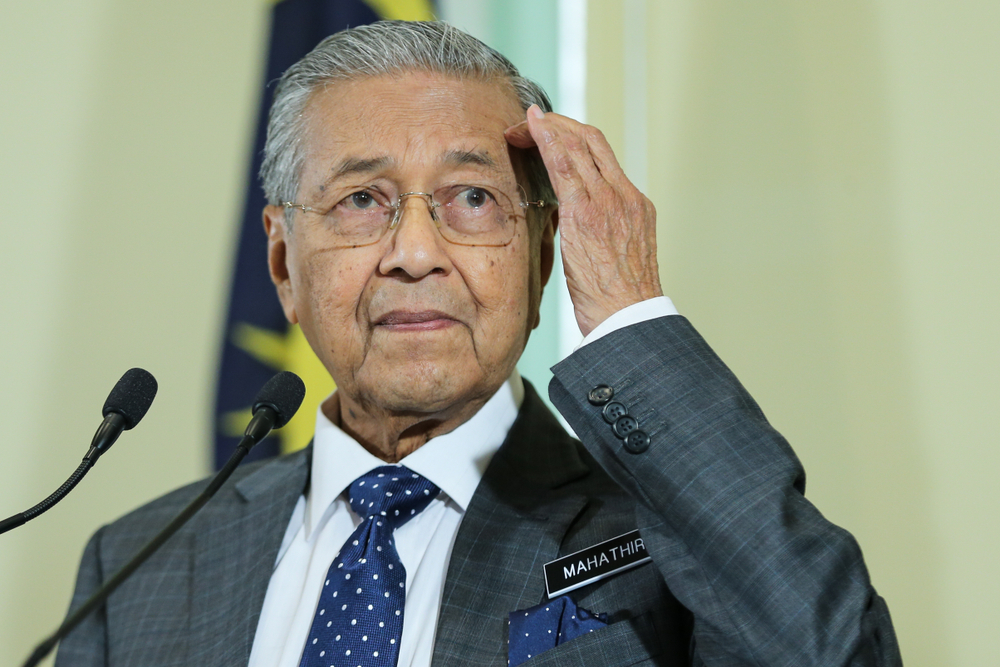

The government has always seen 94-year-old Malaysian Prime Minister, who’s partly of Indian descent, as an inveterate India-baiter. And it was livid after he attacked India’s actions in Kashmir and the Citizenship Amendment Act.

India’s clampdown on Malaysian refined palm oil imports is obviously a major blow to that country’s economy. India imported 28 per cent of Malaysia’s palm oil exports last year. But there’s the possibility of blowback from India’s action. Palm oil is used mainly for household cooking as well as being utilised in a broad range of other products from soap to biscuits.

And this is why Indian consumers may also feel the pain as Indonesian suppliers have started charging a $15-$20 premium over benchmark prices, according to traders. India will be paying these higher Indonesian palm oil prices at the same time as it is struggling to curb inflation of 7.4 per cent, the strongest level since 2014, led by surging food prices.

Malaysia’s refined palm shipments to India totalled 2.66 million tonnes last year, according to Malaysian Palm Oil Board figures. Even at the lower end of the quoted Indonesian palm-oil premium, India would pay around $40 million extra for a 12-month supply of refined palm oil, supposing it imported the same amount from Indonesia it did last year from Malaysia.

India’s strong reaction to Mahathir’s repeated criticism of the scrapping of Article 370 and the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) has also driven a stake into the government’s drive to make Malaysia a “priority country” under its “Act East Policy,” which the government has billed as an upgrade from its previous “Look East Policy”.

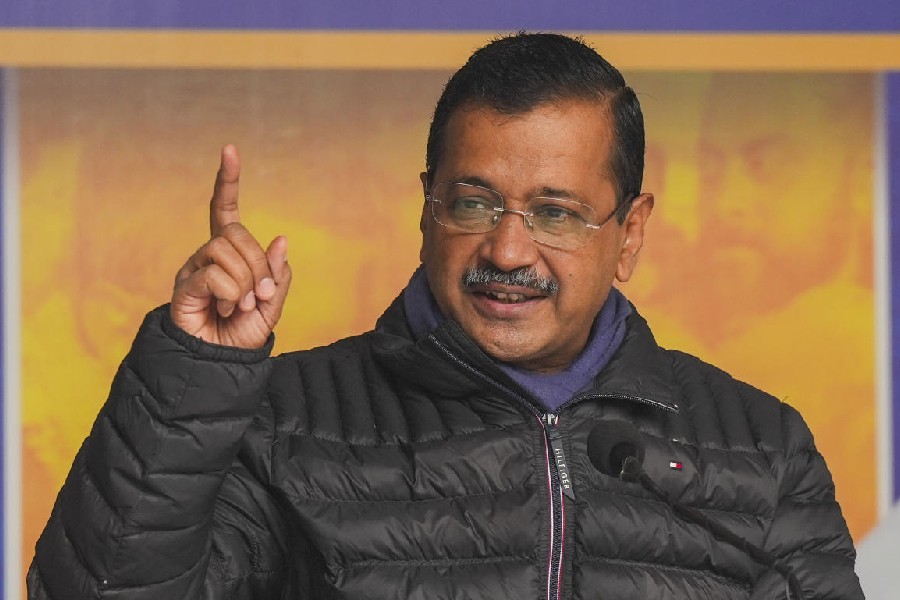

New Delhi’s actions against Malaysia are understood to be being directly driven by the Prime Minister’s Office, rather than the Minister of External Affairs S. Jaishankar, who was previously a career diplomat and is known as a seasoned, steady foreign policy hand.

Back in 2015, the Modi government struck an “enhanced strategic partnership” with the previous Malaysian government under Prime Minister Najib Razak. But after Mahathir’s 2018 election comeback, Malaysian-Indian relations began to sour.

New Delhi was particularly riled when Mahathir accused India at the UN General Assembly last September of having “invaded and occupied” Kashmir. There are other big bilateral irritants too, including Malaysia’s refusal to extradite Zakir Naik, the vitriolically anti-Indian preacher, and the country’s stepped-up dealings with Pakistan that Kuala Lumpur hopes will buy more of its palm oil to cover the loss created by India.

New Delhi registered its strong displeasure with Mahathir’s UN speech in diplomatic statements in September and imports of Malaysian palm oil started coming down that same month when the government hiked import duties on the palm oil by 5 per cent.

Then, in January, after Mahathir called the CAA “grossly unfair” toward Muslims, the government upped the ante. It issued a notification putting import of refined palm oil under the “restricted” rather than “free” category which means importers must get a government licence to purchase the commodity.

The has also “informally” told traders to stop crude Malaysian palm oil purchases and only buy from Indonesia, which would be a boost to domestic refiners, though the commerce ministry has denied this.

Malaysia, in a bid to mollify India and reverse the economic hit to its domestic economy, has now in placed orders for 130,000 tonnes of Indian raw sugar worth some $49.2 million, up from 88,000 tonnes it purchased in 2019.

Mahathir says Malaysia’s too small to fight India. “We are too small to take retaliatory action,” the populist warhorse said, when asked if the country of 32 million people would strike back. He added, though, that, “We are concerned, of course, because we sell a lot of palm oil to India. But on the other hand, we need to be frank and see that if something goes wrong, we will have to say it.”

The question is whether using trade as a weapon to counter international criticism -- and there’s been a lot of it -- of the CAA and abolition of Article 370 -- will be the government’s modus operandi going forward with other countries as well. After Malaysia, the government is reported to be considering trade action against Turkey for siding with Pakistan on various issues including proposed blacklisting by the Financial Action Task Force.

If New Delhi does intend to use trade to show its displeasure rather than utilise other diplomatic actions, that could exact a toll down the road. Various Western nations are becoming uncomfortable with what they perceive as the Modi government’s pursuit of an anti-Muslim agenda. Also, while Middle East nations seem unfazed by the government’s actions on Kashmir and the CAA right now, they could be problematic for some Asian Muslim nations like Malaysia.

But the government should keep an eye on Trump’s trade wars and learn from his experiences. His battles with Canada, Mexico and also China, have reaped only minimal benefits and made the rest of the world reassess their relations with an aggressive US that is using strongarm tactics to achieve its ends. India’s palm oil ban has upset Nepal and Bhutan which have become unintended casualties of the Indian action. And South East Asia is expected to be one of the fast-growth areas of the coming decade. For now, the Indonesians are benefiting from the palm oil wars but the countries in the region may become more wary of India in future.

Rais Hussin, chief executive of Malaysia-based think-tank Emir Research, noted in a recent paper that trade wars are “toxic” for the value chain. By weaponising trade, 'India is destroying a key principle of its own diplomatic engagement with the East Asian region,” he said.

(An earlier version of this story was published online on 25 January 2020.)