Kashmir has lost not just its special status but also its azadi to speak.

A bond the government is forcing detainees, including top politicians, to sign to secure their release bans them from speaking against “the recent events” in Jammu and Kashmir — a thinly veiled reference to the changes to the state’s constitutional status and the security clampdown.

Senior lawyers and rights activists have described this bond — a tweaked version of the standard bond under Section 107 of the Criminal Procedure Code that potential troublemakers are asked to sign — as “illegal” and unconstitutional.

However, state advocate-general D.C. Raina, who denied having seen the new bond, defended it as “absolutely” legal. He said the change in wording was something “which may not amount to a change (but is) an expressive way, a manifestation of the word”.

Scores of people including politicians and academics are believed to have been freed after they signed the bond, while several like former chief minister Mehbooba Mufti have reportedly refused to sign it.

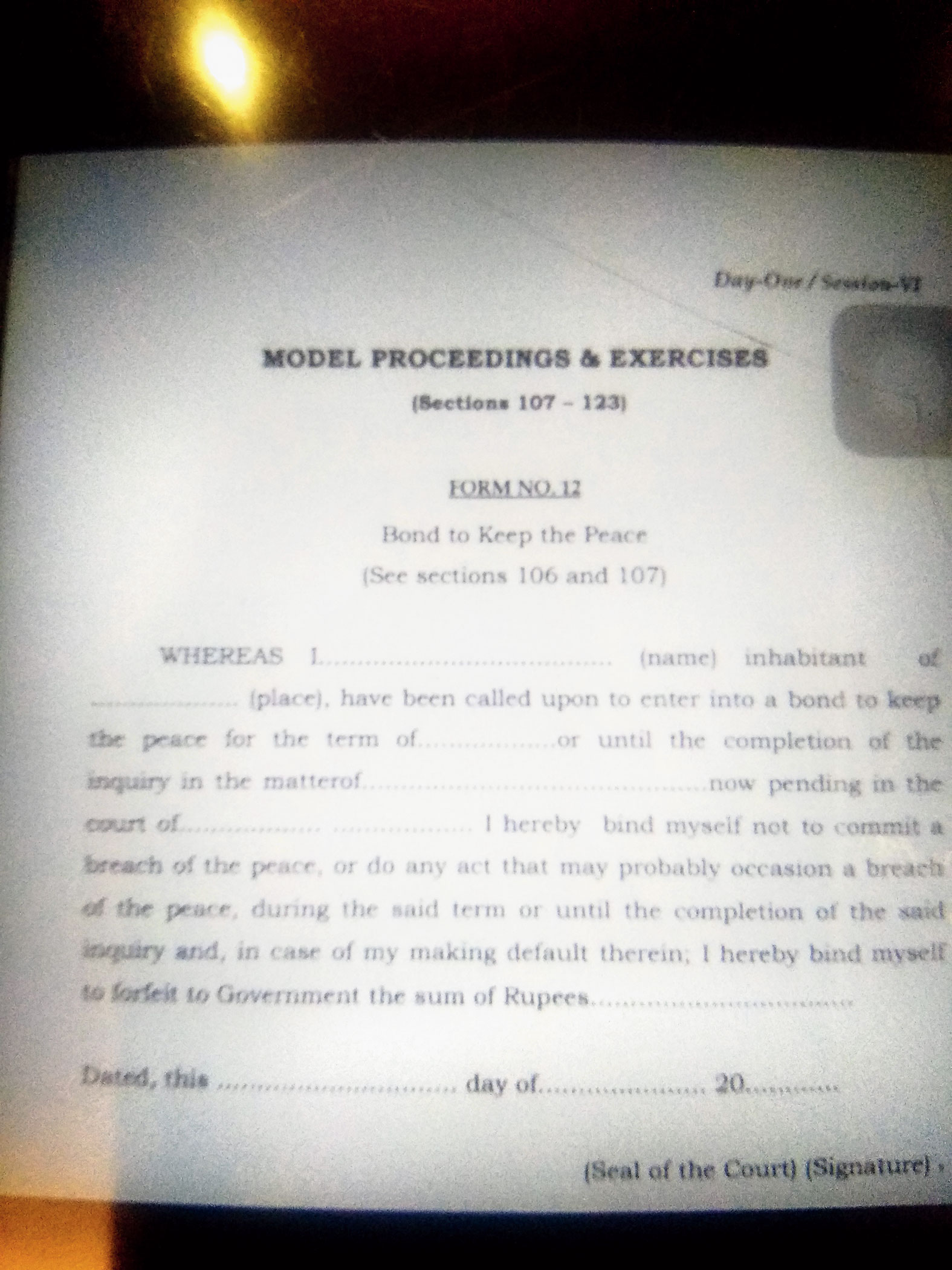

A copy of the standard bond potential troublemakers can be asked to sign under Section 107 of the CrPC. It says: “…I …have been called upon to enter into a bond to keep the peace for the term of…. or until the completion of the inquiry in the matter of…. I hereby bind myself not to commit a breach of peace or do any act that may probably occasion a breach of the peace, during the said term or until the completion of the said inquiry….”

The Telegraph has accessed a copy of the bond along with a signed copy and a magistrate’s order releasing two women that repeats the contents of the bond.

Under the standard Section 107 bond, called the “Bond to Keep the Peace”, potential troublemakers have to undertake “not to commit a breach of peace” or “do an act that may probably occasion a breach of the peace”. Violation brings the forfeiture of an unspecified sum to the government.

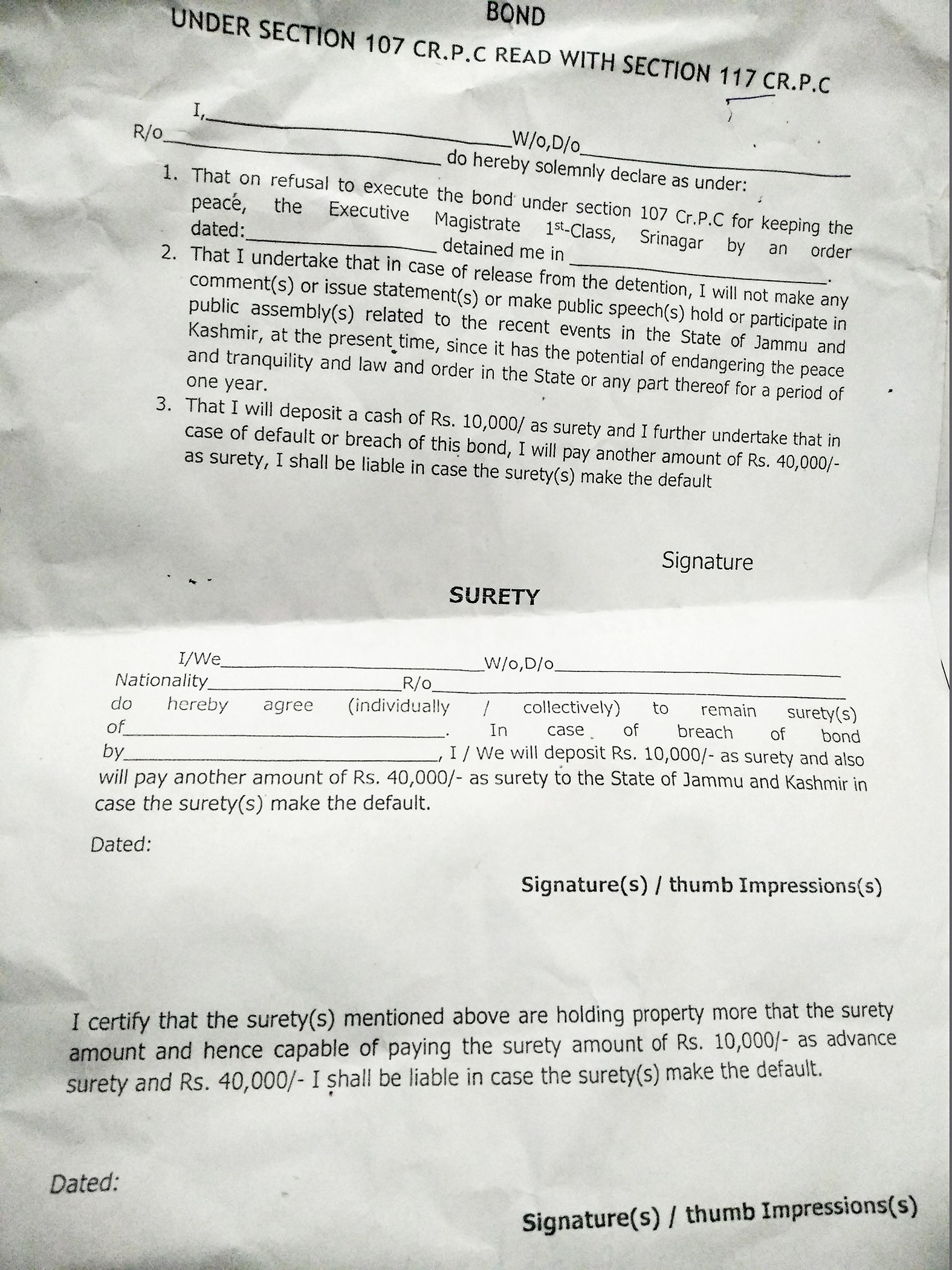

The new version forces the signatories to undertake to “not make any comment(s) or issue statement(s) or make public speech(s) hold or participate in public assembly(s) related to recent events in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, at the present time, since it has the potential of endangering the peace and tranquillity and law and order in the state or any part thereof for a period of one year”.

The signatory has to deposit Rs 10,000 as “surety” and undertake to pay another Rs 40,000 as “surety” for any violation of the bond.

Advocate-general Raina said the purpose of Section 107 was to maintain peace, which can have the “widest connotations”.

“It (the change in language) does not alter or take away the basic spirit. The language is only the format, the sense remains the same…. I don’t think that (considering the bond illegal) will be the right understanding. It falls within the purview of the law,” Raina said.

“I have not seen that (the new bond) but from your expression (after The Telegraph read out its contents) I get it that it is primarily the added expression or manifested form of the same spirit of the language.”

Raina said the version of the CrPC in force in Jammu and Kashmir was different from that in the rest of the country, anyway.

He said that while the state legislature can amend the provisions, the state government can “further elaborate, make it viable, prescribe more manner and method” as long as the primary objective remains unchanged. He said that under governor’s rule, the governor has the power to amend the language of Section 107.

Ironically, a desire to do away with the arrangement that allowed Jammu and Kashmir its own versions of laws was one reason the government revoked the state’s special status.

A copy of the bond detainees in Kashmir have to sign now if they want freedom.It says: “…I undertake that in case of release from the detention, I will not make any comment(s) or issue statement(s) or make public speech(s) hold or participate in any public assembly(s) related to the recent events in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, at the present time, since it has the potential of endangering the peace and tranquillity and law and order in the state or any part thereof for a period of one year.”

Senior additional advocate-general Bashir Ahmad Dar, counsel for the home department, said he couldn’t comment offhand on the matter. He too denied “knowing anything about” the new bond.

High court lawyer Altaf Khan, also counsel for the protesting women released this week, said the bond was “illegal” because it “contradicts the Constitution”.

“This (bond) is all new.… They can make changes but those changes have to be in accordance with the law,” he said.

Khan said the women were additionally asked to sign an affidavit “apologising” for the “mistake” (of holding a protest) and “not to repeat it in future”, but they refused.

Another high court lawyer, Anwar-ul Islam Shaheen, said the bond violated the fundamental right guaranteed by Article 19 (free speech and expression) of the Constitution.

Raina, however, claimed that criticism was the “hallmark of democracy” but the context “in which you criticise and by which manner and method you criticise” have to be seen.

Rights activist Khurram Parvez said the government had arrested 5,000 to 6,000 people during the 75-day-old clampdown, and many of them had been released under this bond. The government has refused to reveal the number of detentions during the period but claims it is far less.

Khurram said the government was also forcing 5 to 20 people to sign a community bond — sort of a guarantee — to secure the release of every person arrested under Section 107. He said “many thousand” people — mostly relatives or neighbours — would have signed this bond.

This newspaper recently spoke to the family of a nine-year-old boy, the youngest victim of the clampdown, who was allegedly detained for two days. The family was forced to bring around 20 people — relatives and acquaintances — to give it in writing that the boy would not commit any offence in future.