Economists Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer have won this year’s Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

The prize, popularly known as the Economics Nobel, was conferred on them for their “experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said on Monday.

“Yes, I am happy,” the Calcutta-educated Banerjee told The Telegraph over the phone.

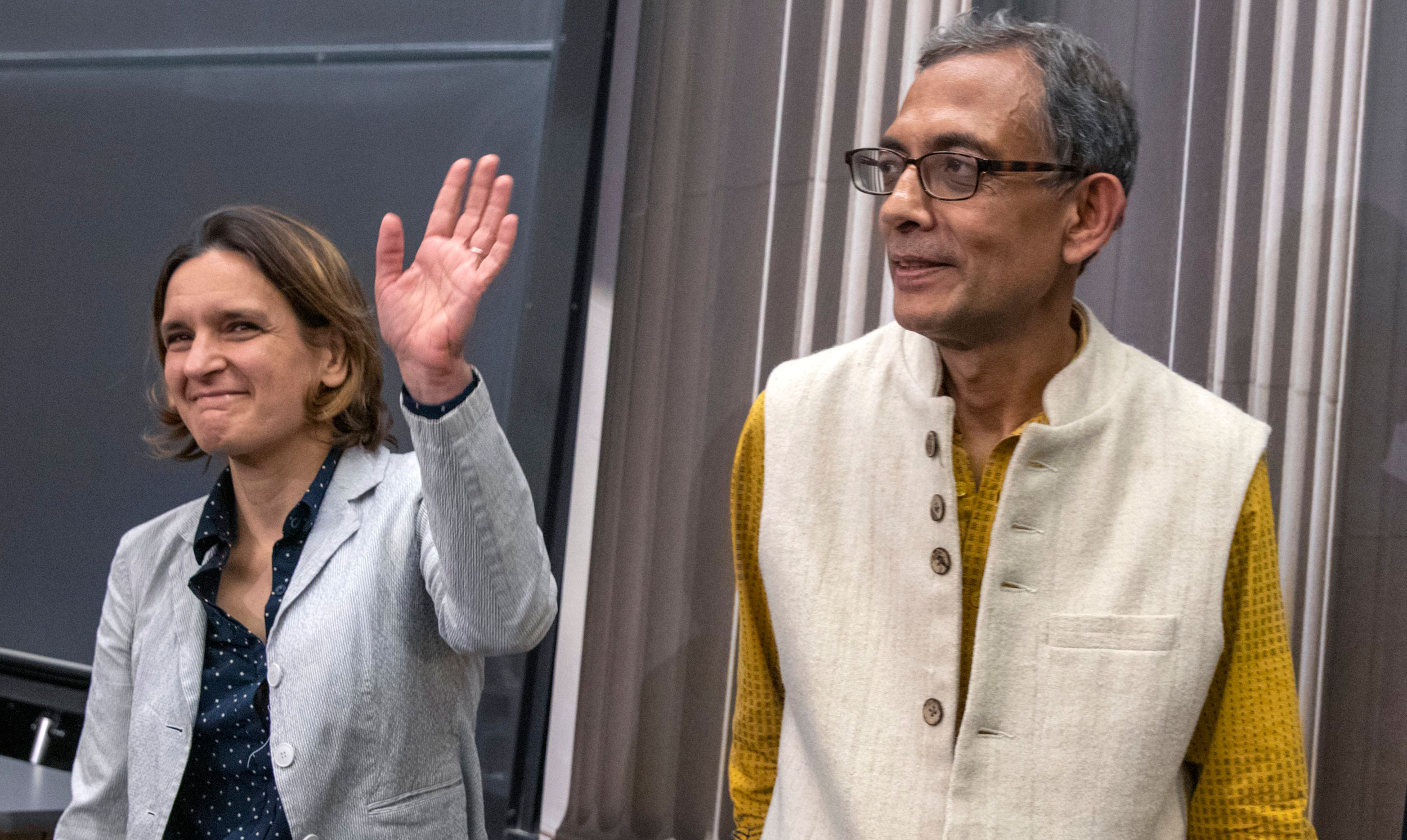

Duflo, who is married to Banerjee, becomes only the second woman economics winner in the prize’s 50-year history, as well as the youngest at 46. Only five other married couples have won the Nobel together. The three winners share the 9 million-kronor ($918,000) cash award.

Banerjee, the Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is a passionate cook and a classical music aficionado.

He had once described himself to this correspondent as an old-fashioned social scientist, who had co-founded the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab for research towards alleviating global poverty.

On Monday, the award came as a recognition for randomised controlled trials (RCT), an approach pioneered by Banerjee and his wife that has received wider traction than conventional empirical methods in development economics.

“When we started these randomised controlled trials around 25 years ago, people used to ask why we were doing these. There were people who would say they were aware of the problems and knew what had to be done. We were accused of wasting people’s money and time,” recalled Banerjee, who had received the good news through a call from Goran Hansson, secretary-general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, at 4.45am on Monday.

Banerjee went back to sleep — but for only 45 minutes. Congratulatory calls — for both him and Duflo — started pouring in from across the globe.

The boy from Calcutta, who studied at South Point and then the erstwhile Presidency College, could not forget the “arguments by authority” he and Duflo had to face when they decided to use RCT to find out more about the lives and choices of the poor and possible ways of fighting global poverty.

“There is a need for forbearance…. You have to create a space for those who have different views or ideas,” said Banerjee, the second Indian to win an Economics Nobel after Amartya Sen.

The significance of the message cannot be missed in contemporary India as the hegemony of the dominant opinion is shrinking the space for alternative views and ideas.

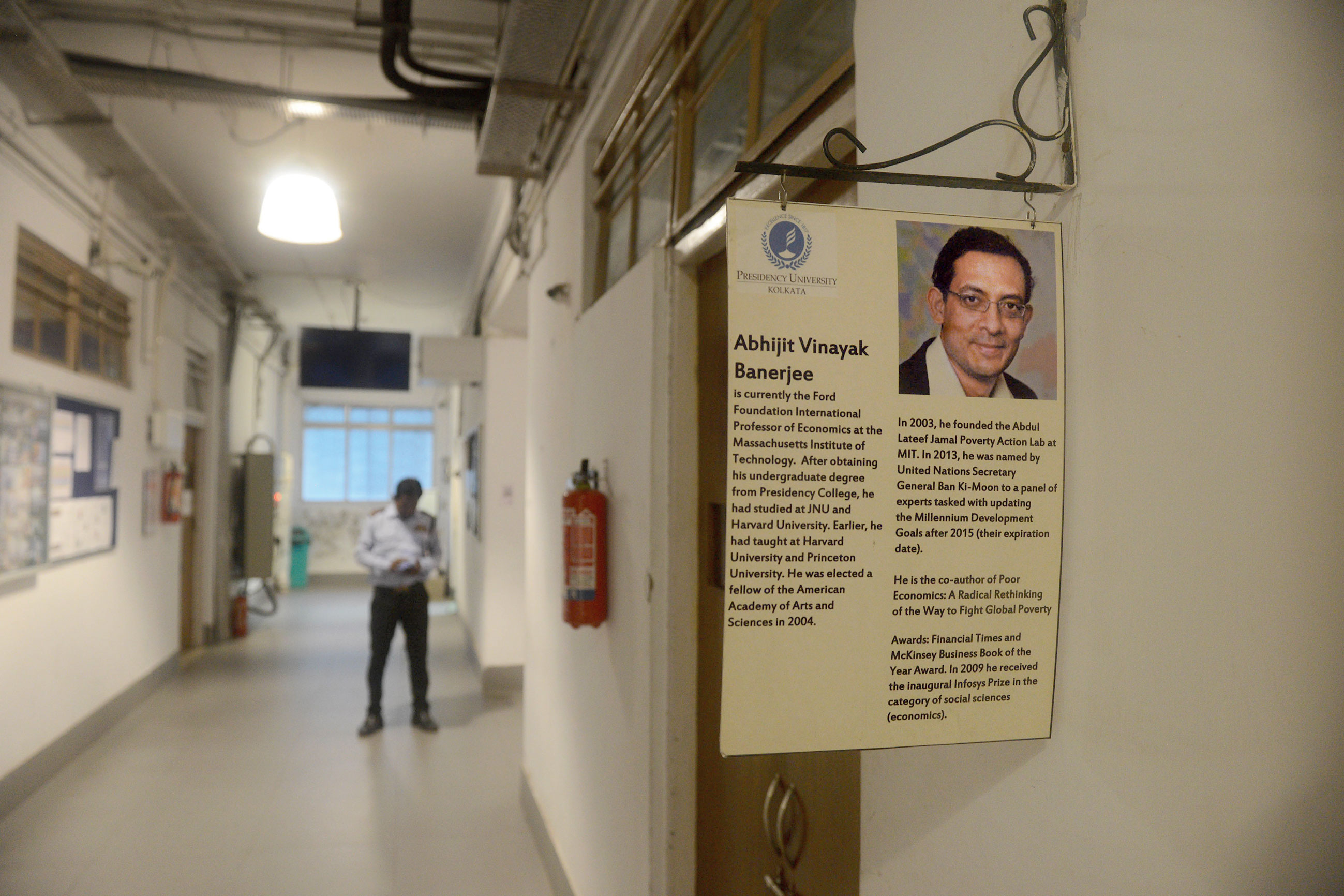

A display board in the corridor of the economics department of Presidency University in Calcutta features Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee. The students of the department had put up several such boards in 2016, ahead of Presidency's bicentennial celebrations in January 2017, to recognise the contributions of some of the brightest alumni and faculty who included Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee’s father Dipak Banerjee. Picture by Bishwarup Dutta

Last March, Banerjee and Duflo had joined over 100 economists and social scientists in seeking an end to political interference in statistics institutions in India. They had appealed for the restoration of the integrity of economic data after allegations surfaced that jobless figures had been suppressed.

On Monday, referring to the Nobel for Banerjee, Kaushik Basu, former chief economic adviser to the finance ministry, told this newspaper: “The award is a celebration of ideas.”

Basu said Banerjee’s achievement was a reminder of the importance of new ideas and scientific thinking at a time the Indian economy was going through difficulties.

“With the Indian economy going through a difficult patch, with growth severely down, this is a reminder of the importance of new ideas and scientific thinking. Their application of randomised control trials is being used all over the world in programmes to improve education and health and to alleviate poverty,” said Basu.

Banerjee told the ABP Ananda news channel on Monday: “The condition of the Indian economy is not healthy…. Whatever I’m seeing, I cannot feel reassured. Around 5-7 years ago, there were concerns like the environment, but at least there was growth in the economy. Now, that’s not the case.”

Taking a leaf out of the natural sciences’ book, medicine in particular, RCT assesses the effect of a particular treatment by separating a population of subjects into those who receive the treatment and those who remain a control group.

As individuals are randomly assigned to one or the other group, a causal relationship between a treatment and outcomes can be obtained, which can be used in framing public policy.

Though economists have been using RCT in development economics and applied microeconomics in recent years, there have been several questions – like whether results of an RCT can be extended to other places and times than where the original experiment took place – on its wider applicability.

Economist Maitreesh Ghatak, who teaches in London School of Economics, said that the most notable part of the prize is an example of how a simple but powerful idea changed the face of development economics as a field and also led to a paradigm shift in development policy evaluation.

“The World Bank and many governments and large NGOs now insist on randomised control methods wherever feasible. It shows the power of ideas and also the importance of implementing them in a way that actually can affect policy, and touches people’s lives,” said Ghatak, who learnt about the news while teaching a paper by Banerjee to his students in LSE.

Like Ghatak, several people eloquently spoke about the power of idea while celebrating the achievement of Banerjee.

Torsten Persson, a Swedish economist who also serves on the Nobel Prize committee, explained the reasons why the committee chose the trio for the award.

He said how experiments by Banerjee and Duflo revealed that the primary problem in education in many low-income countries was that teaching was not sufficiently adapted to the pupils’ needs.

“Banerjee, Duflo et al. studied remedial tutoring programmes for pupils in schools in Mumbai and Vadodara. These schools were ingeniously and randomly placed in different groups, allowing the researchers to credibly measure the effects of teaching assistants. The experiment clearly showed that help targeting the weakest pupils was an effective measure in the short and medium term,” said Perrson.

According to him, such “wise, cost-effective and new ideas” need to be adopted to help the poorest of the poor in globe. “And when resources are scarce, it’s important to use wise and new ideas and implement them in a cost-effective manner,” he added.