India should consider reducing the Covishield dose gap to eight weeks from the current 12-16 weeks, sections of experts have said amid new evidence that the coronavirus variant called B.1.617.2 has triggered explosive outbreaks and caused infections in partially immunised people.

The evidence from India’s National Centre for Disease Control and the Institute for Genomics and Integrative Biology in New Delhi has indicated that B.1.617.2 is “over-represented” (appears more frequently) in post-vaccination breakthrough infections than in the general population.

“B.1.617.2 is capable of creating fast-rising outbreaks with vaccination breakthroughs,” researchers at the NCDC-IGIB said in their study. “We would reemphasise that prior infections… and partial vaccination are insufficient impediments to its spread.”

A worker sprays disinfectant to sanitise a mall ahead of its reopening as the unlocking process of the Covid-19 lockdown begins in New Delhi on Sunday. Prem Singh

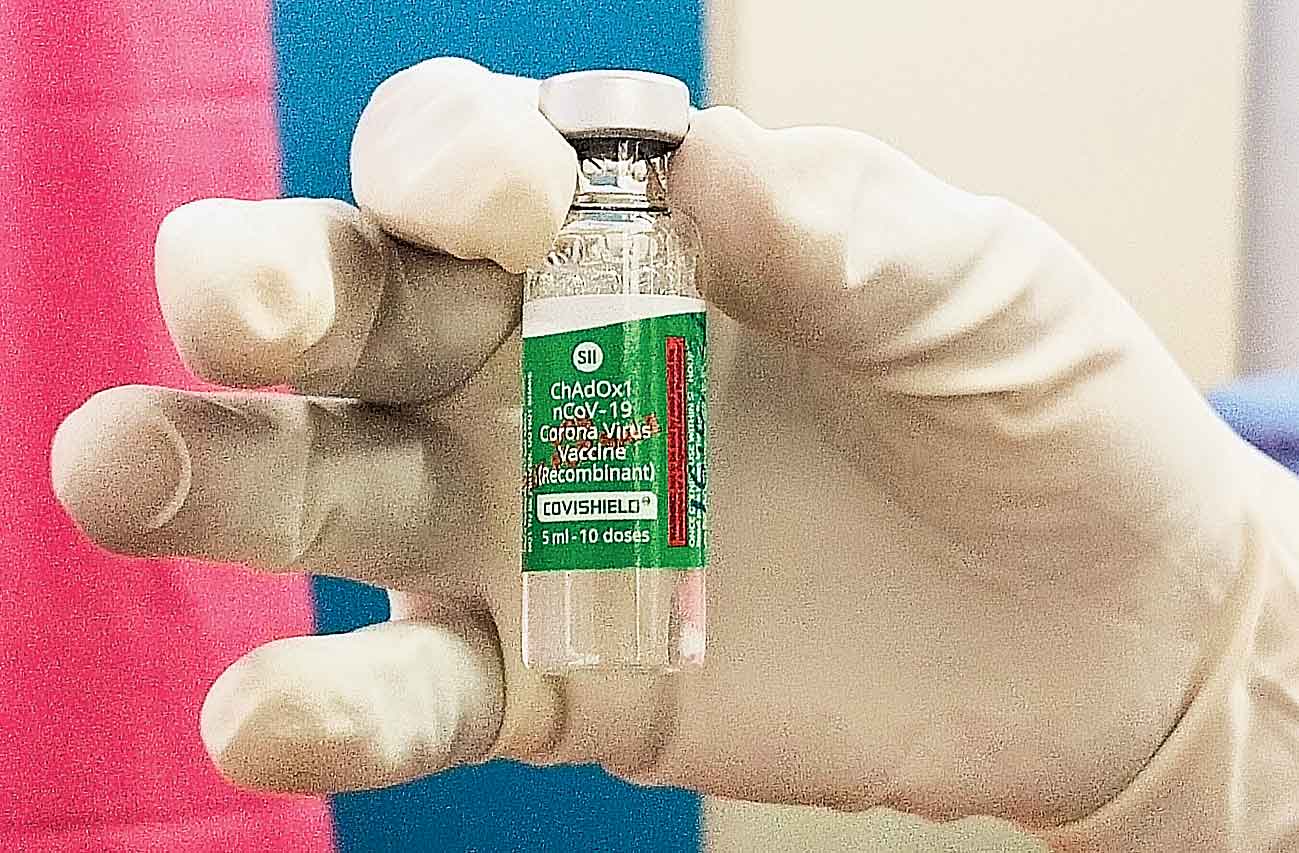

A UK study whose findings emerged on May 22 had found that the AstraZeneca vaccine — Covishield in India — was 33 per cent effective against symptomatic Covid-19 cause by B.1.617.2 three weeks after the first dose and 60 per cent effective after the second dose.

Health authorities in the UK had cited those results and reduced the AstraZeneca vaccine’s dose gap from 12 weeks to eight weeks, prompting sections of experts in India to call on this country’s vaccination advisers to reduce the gap for Covishield too.

Experts have underlined that the observed 33 per cent protection against B.1.617.2 after the first dose was lower than the 50 per cent protective threshold prescribed by the World Health Organisation and adopted by India’s regulatory authorities.

“India should consider the shorter interval between two doses because we know this variant is in wide circulation in the country,” said K. Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India, New Delhi, a research and training institution.

Reddy and others believe the NCDC-IGIB results bolster the evidence for a shorter gap. Among a set of 27 people who had breakthrough infections, B.1.617.2 accounted for 19 (76 per cent) cases.

The study suggests that B.1.617.2 had played a key role in Delhi’s sharp surge in the 7-day average of daily new infections that increased from less than 400 cases in early March to over 20,000 by April-end.

“This is real-world evidence from India — this lends support to arguments for shortening the gap to 8 weeks,” said Santhanu Tripathi, former professor and head of pharmacology at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine. “When new knowledge comes in, we must examine it and, if acceptable, apply it.”

But the country’s vaccination advisers had in mid-May expanded Covishield’s dose gap to 12-16 weeks from their earlier recommendation of 6-8 weeks and appear unwilling to so quickly revise the gap alongside the UK and lower it to eight weeks.

Narendra Arora, a senior adviser to the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (NTAGI), an expert panel that guides the government on vaccines, said the panel would wait for more evidence to emerge and take into account observations in India before taking a decision on the dose gap.

“We will look at all available evidence in two or three months – and if required reconsider the dose interval,” another member of NTAGI who requested not to be named told The Telegraph.

The current dose gap of 12-16 weeks would allow the country to provide more people first doses of Covishield while those who have received the first dose wait for their second dose.

A senior vaccine science specialist said it was still unclear what would yield India the greater public health gains – immunising more people with single doses during the 12-16 week dose gap and taking a chance with breakthrough infections, or shortening the dose gap and ensuring as many people receive two doses in the shortest possible time.