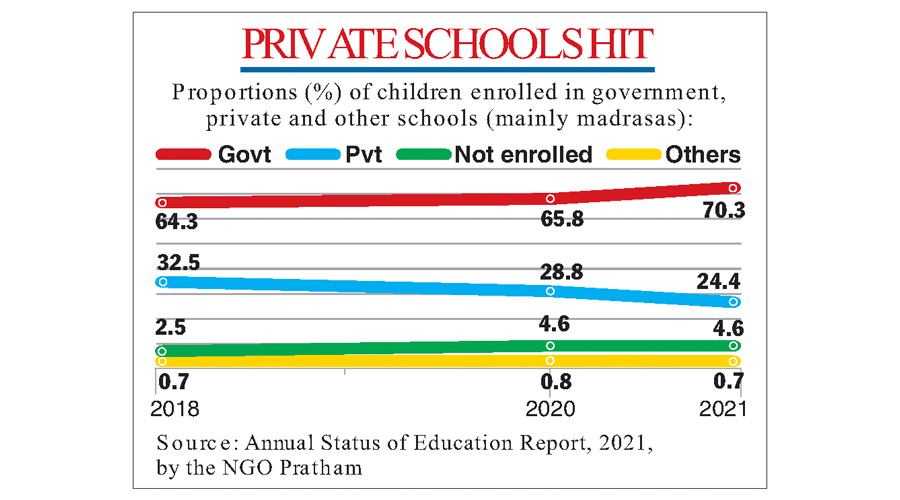

Enrolment in private schools has fallen sharply since 2018 and the proportion of un-enrolled children has nearly doubled, says a sample survey that attributes the trend mainly to the pandemic’s effect on household incomes.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2021, released by the NGO Pratham on Wednesday, has recorded a drop of more than 8 percentage points in private school enrolment from 2018.

This has been accompanied by a rise of 6 percentage points in government school enrolment and an 84 per cent jump in the proportion of un-enrolled children, from 2.5 to 4.6 per cent of all children aged 6 to 14. (See chart)

Both before and after Covid, the proportion of girls enrolled in government schools has been higher than that of boys, according to the ASER report, based on a telephone survey of over 75,000 households from 581 districts.

Rukmini Banerji, chief executive officer of Pratham, said the phone survey had covered 90 per cent of the same sample that a house-to-house survey had covered in 2018.

“Nearly 10 per cent of the households surveyed in 2018 had no telephone. So, they could not be covered this time,” she said.

“Had they been covered, the (proportion of) private enrolment would have been even less (because these families are likely to be poorer).”

Banerji attributed the trend mainly to Covid hitting incomes. She suggested that the un-enrolled children were mostly very young children who were expected to enrol after the pandemic situation improved.

Yagnamurthy Sreekanth, principal of the Regional Institute of Education, Mysore, attributed the latest enrolment trend to the incentives government schools offered and the opening of English-medium schools by certain state governments, apart from the financial problems faced by households.

“Government schools offer incentives like free uniforms and textbooks — even free bicycle and gadgets (such as tablets) in some states. States like Andhra Pradesh have switched to English-medium education in government schools already,” Sreekanth said.

The ASER report said enrolment in private schools had risen sharply between 2006 and 2014 to reach around 30 per cent of all enrolment before plateauing.

The rise was driven by a mushrooming of budget private schools and an improving economy changing lifestyles and fanning parental aspirations for their children.

Sreekanth said people working in the unorganised sector were the worst hit economically by the pandemic. It’s this segment that mostly sent its children to budget private schools, many of which have closed down in the past two years, he added.

“All this has brought a positive vibe to government schools. The challenge now is to retain these children. The government schools have to provide quality education and leverage information communication technology for effective learning,” Sreekanth said.

He said the immediate challenge was to address the “learning gaps” among the children caused by the prolonged pandemic-induced school closure.

“Once the children are equipped, they should be taught the new concepts,” he said.

From 30 per cent in 2018, the proportion of children taking private tuition has increased to 40 per cent, probably because of the school closure.

The availability of smartphones has risen from 36.5 per cent in 2018 to 67.6 per cent in 2021, with the schools resorting to online education. Some 79 per cent private school students have a smartphone at home, compared with 63.7 per cent of their government school peers.

The proportion of schoolchildren who received learning support from family members at home fell from 75 per cent in 2020 to 66 per cent in 2021.

The closure of schools last year had necessitated parental guidance, and the job losses had given many parents time to devote to their children. The resumption of work this year has reduced the opportunity — and the increase in private tuition lowered the stark necessity — for parental help.

The overall rise in government school enrolment has been driven by states such as Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh.

The 2020 survey too was done over the phone. While the survey has been a two-yearly exercise in recent years, it was repeated in 2021 because of a felt necessity to chart the effects of the pandemic on school education.