The Narendra Modi government on Friday announced major legislative changes designed to change the fortunes of India’s cash-starved farmers but appeared to set itself up for a battle with the states over the constitutional propriety of the amendments that seek to abridge the states’ governance rights.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman came out with her third tranche of the Rs 20-lakh-crore stimulus package that Modi had promised, which was again short on spending commitments but expansive on the promise to provide farmers better remuneration for their produce.

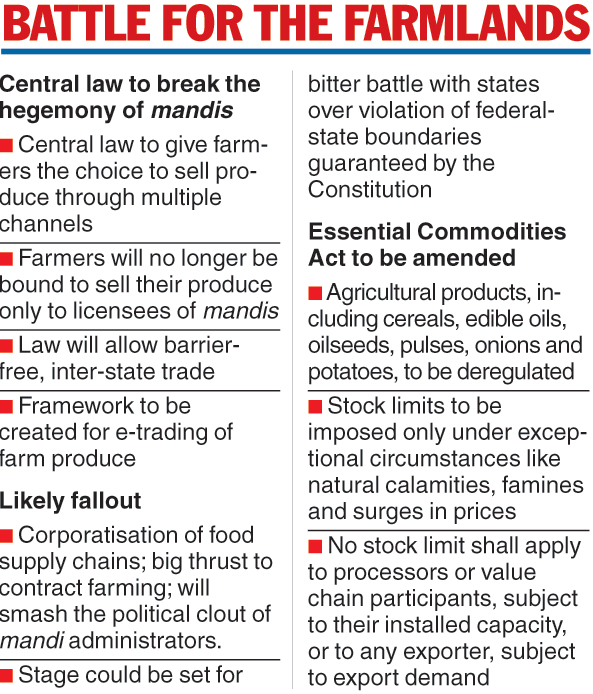

Two big changes have been proposed: the first to break the hegemony of the mandis — the over 2,000 wholesale markets — in a quest to create a national common market for agricultural commodities.

The idea has a seductive appeal and several governments have tried to achieve the same objective. But they have faltered in the face of stiff opposition, including from big farming goods producing states and a ragtag of stakeholders who thrive on the revenues that the mandis derive from the levies they charge.

The other proposal is to amend the Essential Commodities Act to remove stockholding restrictions and trading curbs on farm products. The changes, etched very vaguely at this stage, could potentially open the doors to expansive contract farming and the corporatisation of food supply chains.

The Modi government is hoping to bring in the legislative changes with the broad objective of freeing prices, production and trade in agriculture from a chain link of middlemen and decades of corruption-ridden practices.

Hornets’ nest

But while seeking to break the stranglehold of the wholesale markets established under the Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) Acts enacted by the state governments, the Modi government could be stirring up a hornets’ nest.

The mandi managers enjoy enormous political clout and act as a source of funds that further a variety of political interests in their regions.

“There is a perception that the positions in the market committee (at the state level) and the market board – which supervises the market committee -- are occupied by the politically influential,” the Economic Survey of 2014-15 had said in a chapter dedicated to the subject of creating a national market for agricultural commodities.

“They enjoy a cosy relationship with the licensed commission agents who wield power by exercising monopoly power within the notified area, at times by forming cartels. The resistance to reforming APMCs is perceived to be emanating from these factors.”

The report had added: “APMC operations are hidden from scrutiny.”

Sitharaman said the government would soon formulate a central law to ensure barrier-free inter-state trade along with a framework for online trading of agricultural produce.

This would throw open the doors of national markets for farmers, allowing them to sell their produce “wherever” and to “whoever”, thereby shaking off the current restriction that requires them to sell only to the licensees at the mandis.

The finance minister said the farmers should have the choice to sell their produce through a variety of channels and extract the best price for their produce.

The objective is noble and may work in theory but will flounder in practice as it could easily trade in an old, home-grown wheeler-dealer network for a new, swashbuckling bunch of buccaneers, leaving the farmer just as destitute as he is now.

The government said it would bring in a “legal framework” that will help farmers predict the prices of crops at the time of sowing, and engage with processors, aggregators, large retailers and exporters. The framework will also help mitigate the risks for farmers and standardise quality in the agriculture sector, Sitharaman added.

Under the provisions of the APMC Act, farmers are required to sell their produce only at designated mandis at prices that are often regulated and many times lower than the prevailing market price.

This restricts the earnings of the farmers and curbs their ability to take their produce for further processing or exports.

While several states have agreed to abrogate or change the APMC Act and abolish the mandi system, it remains the principal market for farmers.

Remunerative prices

Critics of the Modi government have accused it of trying to deflect attention from the fact that it has been unable to fork out money to the farmers through the procurement programme it is supposed to run.

The minimum support price that underpins the procurement programme has been the traditional way to ensure that farmers are not taken for a ride by the middlemen.

Congress spokesperson Randeep Surjewala said the Modi government was making another fraudulent promise through the legislative changes, arguing that the government’s failure to provide remunerative prices for the current rabi crop had led to a situation where the farmers’ collective loss amounted to Rs 50,000 crore.

“The Modi government has not done anything to deal with this agrarian distress,” he said.

Rakesh Tikait of the Bhartiya Kisan Union feared the government was looking to dismantle the minimum support price mechanism itself and that this seemed the first step in that direction.

“Most of the farmers are small and marginal ones who cannot move their produce to far-off places even when they know they can get a better price there. Farmers cannot don the hats of traders and scout for prices and transport the produce,” he said.

“There are pitfalls within the existing mandi system, which needs to be reformed. The entry of big corporate groups will create more trouble as they will use their financial might to drive down prices, accentuating the crisis that the farmers already face.”

Tikait added: “The farmers already battle the vagaries of the weather; they should not be left at the mercy of powerful market forces.”

Agriculture economist Abhijit Sen said: “The attempt to dismantle the mandi system has been afoot for the past two decades. The inter-state movement of goods is a concurrent-list subject and the present government with its numbers in Parliament and the power it wields in several states is making yet another attempt.”

He added: “The big corporates are interested in bypassing the mandis with the help of aggregators to move the goods. State governments earn a huge sum through the mandi tax and they would have no problem with the movement of farm produce if the tax is paid.”

Ashok Gulati, agricultural economist and former chairman of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, who has been arguing for the dismantling of the mandi system for several years, said: “It is a directional change in the agriculture sector and a long-awaited reform measure, which will break the monopoly of a few in the mandis. It will result in better price discovery for farmers, and the consumers will also benefit because of competition.

“It will also result in better storage facilities and other logistics to boost farming and encourage the entry of the private sector in a big way.”

Rajneesh Kumar, senior vice-president of the Flipkart group, said in a tweet: “APMC reforms are most critical to improve farmers’ lives. This along with demand/mkt driven sowing, robust infrastructure including price discovery will increase farmers’ income & in turn drive economic growth in India.”

Other measures

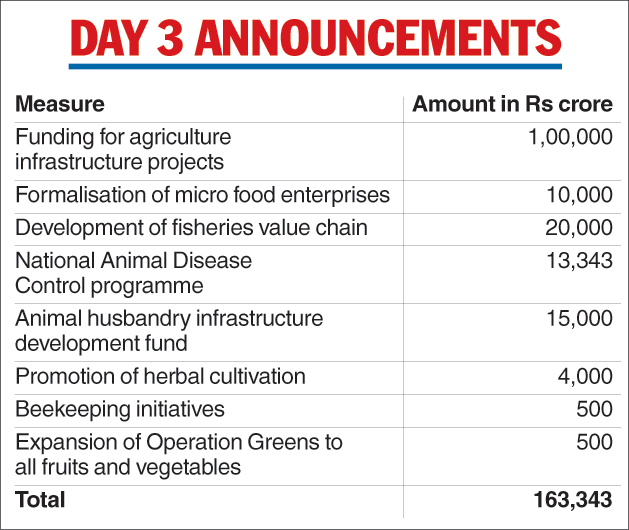

Sitharaman also unveiled a plan for a Rs 1-lakh-crore farm infrastructure fund, to be created by the National bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (Nabard). This will help create adequate cold supply chains and post-harvest management infrastructure, she said.

The government announced a Rs 10,000-crore fund to set up micro food enterprises under a “cluster approach”.

The Modi government’s third tranche of the stimulus package totalled Rs 1.63 lakh crore but, like the previous tranches, did not entail any direct cash transfers.