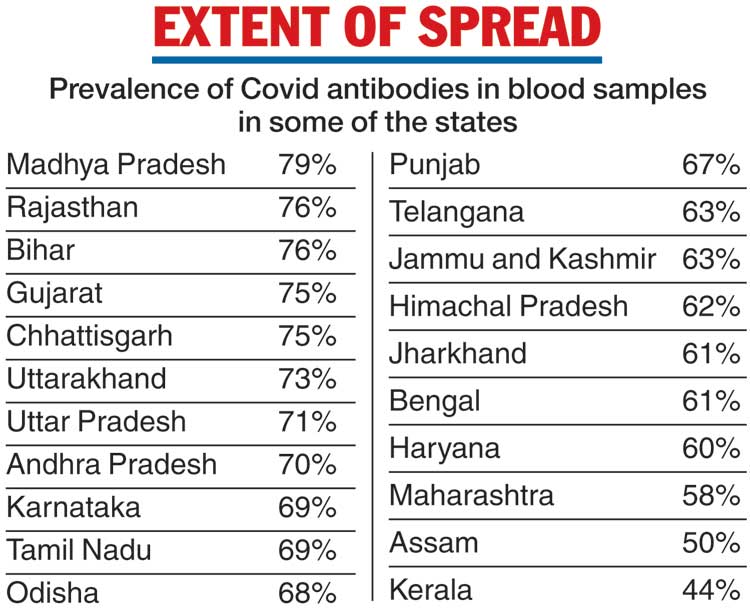

The Centre has asked all states to determine what proportions of people have acquired antibodies against Covid-19 in their districts amid wide variation across states — from over 75 per cent in Bihar, Gujarat and Rajasthan to 44 per cent in Kerala.

The Union health ministry said on Wednesday that it had asked all states to generate district-level data on prevalence of antibodies — a possible signature of protection from the coronavirus — that could be used to guide vaccination campaigns and public health measures.

The ministry also released state-level data from a nationwide survey by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) that health experts say suggest that some states such as Assam, Kerala and Maharashtra remain particularly vulnerable to continued spread of the virus.

The survey that sampled people from 70 districts in 21 states has found antibody prevalence ranging from 79 per cent in Madhya Pradesh, 76 per cent in Rajasthan and Bihar and 75 per cent in Gujarat to 44 per cent in Kerala, 50 per cent in Assam and 58 per cent in Maharashtra.

Nearly 61 per cent of the samples tested in Bengal were positive for antibodies.

The states with large proportions of people with antibodies — implying prior Covid-19 infections — are likely to have experienced runaway infections during the epidemic’s two waves, health experts said.

On the other hand, the experts said, states such as Kerala or Maharashtra that show lower proportions of people with antibodies appear to have taken stronger containment and public health measures that have protected people from the virus.

“But lower antibody prevalence means more people are susceptible to the infection in such states — so they’re more likely to see continued transmission or even surges,” said Manoj Murhekar, director of the ICMR’s National Institute of Epidemiology (NIE), Chennai, the institution that led the nationwide survey in June-July.

Health experts have said Kerala’s low seropositivity, or antibody prevalence, is likely contributing to the current rise in daily new infections in the state.

The ICMR survey, however, was not designed to capture antibody prevalence data at the district level that could vary widely within states. In Tamil Nadu, for instance, Chennai has an antibody prevalence rate greater than 75 per cent, but in some districts, the number is less than 50 per cent, data generated by the state reveal.

Experts say district-level data could guide both vaccination campaigns and preparatory measures.

“Districts with lower seropositivity levels (antibody prevalence) could be prioritised for vaccinations,” Murhekar said. State authorities could also channel healthcare resources into districts with low seropositivity that are at greater risk of continuing infections or localised surges.

The high prevalence in some states suggests their populations might be approaching herd immunity threshold — a point at which so many people are infected that the virus finds it hard to spread any further in that population — but only district-level data can confirm that.

“Overall, it looks like populations in some states are protected,” said Tarun Bhatnagar, a senior epidemiologist at the NIE. “But only district-level data will give us a clear picture. It is possible we’ll continue to see localised spread and surges — a large nationwide wave appears unlikely, unless the virus mutates again.”

Bhatnagar said a fast vaccination campaign itself would lower the risk of more mutations.