Bengal, among all states, has tested the fewest number of people for the coronavirus but has the second-highest positivity rate after Delhi, possibly because its screening process is focused on high-risk people, epidemiologists have said.

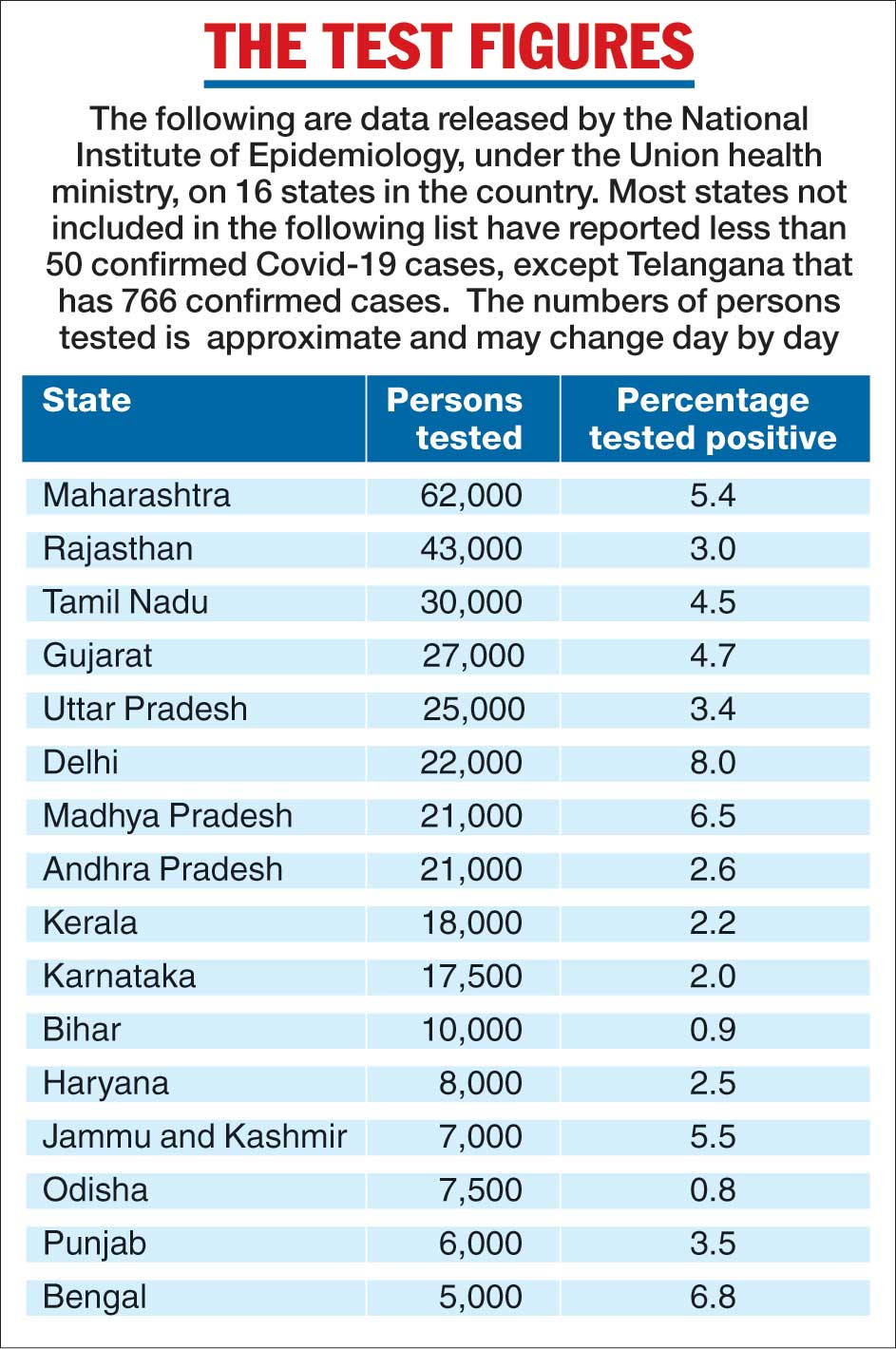

Testing figures from the National Institute of Epidemiology (NIE), Chennai, show that Bengal had until Friday tested fewer than 5,000 people but its proportion of people who tested positive was 6.8 per cent, below only Delhi’s rate of 8 per cent.

Telegraph chart

In contrast, Bihar and Odisha have tested nearly 10,000 people each but have smaller positivity rates — 0.9 per cent in Bihar and 0.8 per cent in Odisha. Bengal had till Saturday recorded 287 confirmed cases, while Bihar had 83 and Odisha 60.

The three states account for 2.8 per cent of the 14,792 confirmed cases nationwide.

Medical experts say a mix of the testing criteria, contact-tracing efficiency and the degree of vigilance of the district-level surveillance systems could explain the relatively lower Covid-19 testing rates in Bengal, Bihar and Odisha.

Bengal had till a week ago tested less than 30 people per million population, the lowest in the country, compared with 50 per million in Bihar, 80 per million in Odisha, 400 per million in Kerala and 650 per million in Delhi.

The positivity rate reflects how many people have been tested and who have been tested, experts said.

“High positivity with low numbers of people tested, as observed in Bengal, could mean a selection bias — with most of the testing focused on the high-risk population,” said Tarun Bhatnagar, a senior epidemiologist at the NIE, a unit of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR).

For Covid-19, the high-risk population would mean the close contacts of people who have tested positive, although the testing criteria recommended by the ICMR call for tests also on all patients with severe acute respiratory illness.

“How many are tested reflects the contact-tracing efforts around already identified cases and whether all the contacts are tested irrespective of symptoms,” Bhatnagar said.

Health officials have cited Kerala’s Kasaragod district as an example of efficient contact tracing. The district, which had recorded 162 Covid-19 cases, had through contact tracing placed in home quarantine 17,373 people.

“The number of people who get tested also depends on the efficiency of the local disease surveillance system,” said Oomen John, a senior public health expert with The George Institute for Global Health, New Delhi.

“The surveillance system has to pick up the earliest signals of infections so that contact tracing and quarantining can be initiated before the infection spreads. It is exactly as a smoke detector has to pick up the wisps of smoke before the fire spreads,” John said.

While the ICMR has recommended testing all patients with severe acute respiratory illness, experts say that many people with respiratory symptoms are unlikely to visit healthcare facilities during the lockdown. In such conditions, community surveillance would be required, Bhatnagar said.

An ICMR exercise had last week detected Covid-19 infection in nine hospitalised patients with severe acute respiratory illness in six Bengal districts, signalling community transmission in the state.

Scientists say the hospital detection of Covid-19 is the first signal of undetected cases in the community. “Finding one Covid-19 case among severe acute respiratory infection patients could mean at least around 10 or more cases, symptomatic or asymptomatic, in the community,” Bhatnagar said.