India’s 21-day nationwide lockdown cannot prevent a resurgence of the novel coronavirus, multiple researchers have cautioned while asking policy makers to map the virus across the country and introduce “evidence-based” lockdowns only where needed.

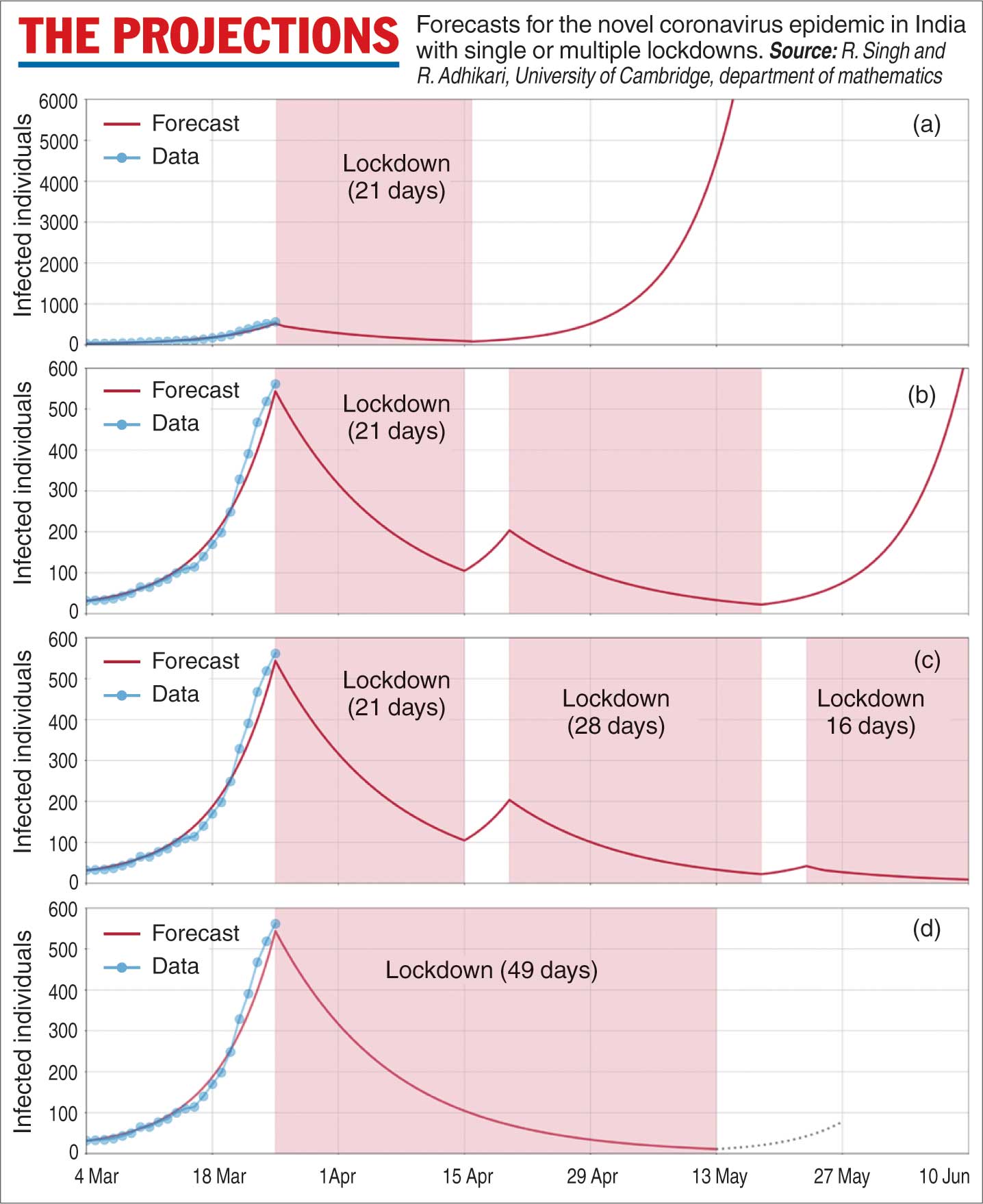

A study by Cambridge University in Britain has suggested that while the lockdown, ordered till April 14, will slow the spread of the virus, the infections will then grow and cross 6,000 by May 13.

The study — not peer-reviewed yet but posted on a scientific archive by the researchers — also suggests that two or three lockdowns with five-day breaks in between or a single 49-day lockdown could stretch the slowdown longer. But the virus will still return.

“Our model looked at the best possible outcomes, and we see a resurgence each time,” said Ronojoy Adhikari, a mathematics researcher in Cambridge who led the study.

The findings are in line with what medical virologists say they expect to see after the lockdown and underscore the need for India to prepare complementary strategies, such as widespread testing and possible localised lockdowns as suggested by other experts.

“The lockdown holds down the virus. After the lockdown, we expect it to bounce back — pockets of infections will flare up somewhere or the other,” said Gagandeep Kang, a virologist and executive director of the Translational Health Science and Technology Institute, Faridabad (Haryana), who was not associated with the study.

Adhikari and his colleague Rajesh Singh have developed the first mathematical model that captures the expected social contacts of people across age groups in India to predict the transmission patterns of the virus.

The contacts, for instance, include grandparents or parents interacting with children at homes, or people in their 30s or 40s interacting in workplaces. The researchers used the model to predict the impact of the virus in the absence of any social-distancing measures and the expected outcomes after lockdowns.

The study has taken into account the virus’s potential to cause severe illness in the elderly and predicted that without any actions, India would lose 370,000 people in their 40s, 900,000 in their 50s, and around a million people in their 60s.

“The numbers point to the magnitude of what the country could face,” Adhikari said in a telephone interview.

He said the model’s prediction of a resurgence even after multiple lockdowns highlights the need for alternative strategies, such as widespread testing and mapping of the virus.

“If we find some hotspots, lockdowns could be localised there,” Adhikari said.

An independent analysis by the US-based Centre for Disease Dynamics Economics and Policy too had last week stressed the need for multiple but localised lockdowns.

“A national lockdown is not productive and could cause serious economic damage, increase hunger, and reduce the population resilience for handling the infection peak,” the CDDEP report cautioned.

Instead, it said, lockdowns should be guided by testing and surveillance and ordered only where they are needed.

A network of public health specialists and physicians had on Friday expressed similar demands, underlining the adverse impacts of a nationwide lockdown and calling on the government to start widespread testing to introduce “evidence-based” lockdowns in select geographical areas.

“Expanded testing is the key. At this point, anyone with mild, moderate or severe symptoms needs to be tested to understand how far the virus has spread in the country,” said Thiagarajan Sundararaman, a community medicine specialist with the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan.

“If we have a picture of where the virus is concentrated, the country can focus its resources better. If (it’s) a part of Uttar Pradesh, you don’t need to lock down Puducherry where the virus might not be such a problem. But for such decisions, we need good mapping.”

India’s cumulative recorded coronavirus count had grown to 694 patients on March 25, the day the lockdown began. But an unknown number of patients are infected and expected to develop symptoms and possibly transmit the virus to only their household contacts during the lockdown.

The curbs on movement are expected to thus slow down the spread of the virus and if all these infected people are picked up by the health system and isolated in hospitals, scientists say, the number of cases in the country could in theory be brought down.

During the lockdown, health authorities could prepare themselves with adequate hospitals, healthcare staff, critical care beds and ventilators to meet the surge in demand that will come.

“When the lockdown is lifted, the newly infected people will transmit the virus in the community, and the virus can come from outside the country,” said T. Jacob John, emeritus professor at the Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Researchers believe that until vaccines against the coronavirus are available, countries would need to periodically implement social-distancing measures to prevent infection numbers from rising too quickly and overwhelming healthcare.

Scientists tracking vaccine development efforts expect the earliest vaccines to emerge only in about 18 months.