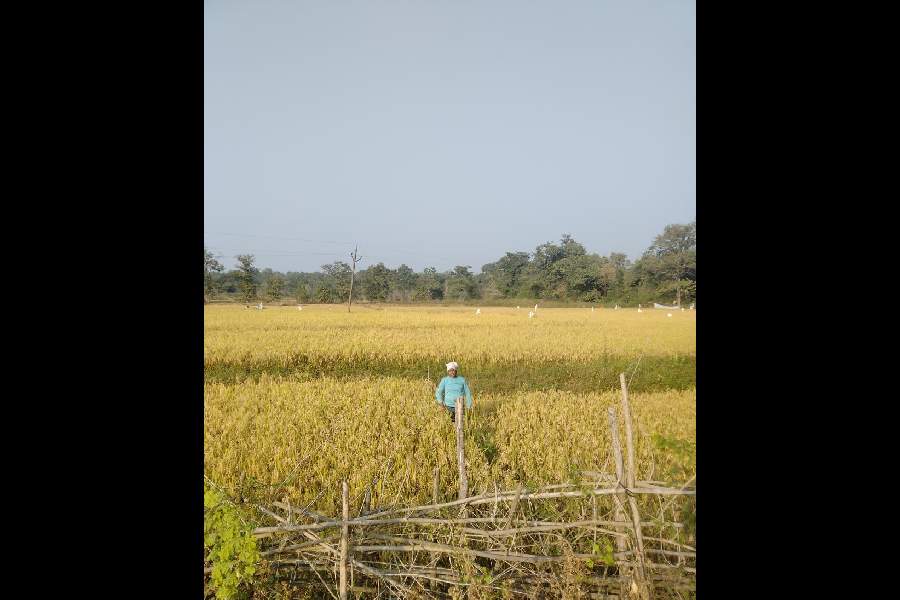

The lockdown has left rural Delhi’s farmers without the hired help they need to harvest their standing crops.

They are getting more worried with each passing day as the window for harvesting, before the crop is lost, gets narrower and narrower.

“Every year, labourers come from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar around this time and we hire them to harvest our crops,” Jitender Yadav, a well-to-do farmer from Jhuljhuli village near Najafgarh, told The Telegraph.

“This year, because of the lockdown, they haven’t come.”

Yadav said he had grown wheat over 15 acres of land and the crop needed to be harvested in two weeks’ time. Even if the lockdown was indeed lifted on April 14 and migrant labourers immediately set off for Delhi, the deadline for them to arrive and finish the job would be tight.

“Our only hope is the cutting machine that I and a group of local farmers are trying to get from Haryana on rent as soon as the lockdown ends,” Yadav said.

Currently, the police are not allowing the harvesting machines to be transported along the roads.

Pradeep Dagar of Dhansa village, who has grown mustard over three acres and wheat over one acre, has a one-week window which will be over before the lockdown ends. He harvested his mustard crop just before the lockdown was announced but could not take the produce to the mandi because of the lockdown.

“If I don’t harvest the wheat crop within a week, the wheat will fall to the ground. But I’m helpless,” Dagar said.

Ravi Srivastava, a labour economist and researcher at the Institute of Human Development, said many farmers faced the same problem in several other states including Kerala, Haryana and Punjab.

He said the Centre had issued circulars to allow farm produce to be transported to markets and workers to work in the fields during the lockdown, but the states had not issued specific guidelines to implement these.

“What is needed is clear-cut guidelines from the state governments to allow the movement of harvesting machines, the inter-state movement of workers, and permission for roadside dhabas to operate where these workers can get food,” he said.

Himanshu, JNU teacher and a researcher on poverty issues, said the best bet for Delhi’s farmers would be to roll up their sleeves and start manually harvesting their crops themselves.

He accepted that this would be a difficult task and there would inevitably be some crop loss.

“At the moment they are waiting for the lockdown to be lifted. But these farmers need to do the harvesting themselves even though there may be some crop loss,” he said.

Paras Tyagi, a law graduate whose organisation, Centre for Youth, Culture, Law and Environment, helps take farmers’ issues to the government, highlighted another problem: that of procurement and storage. With the state government deciding in 2008 that Delhi --- with its 34,000 hectares of farmland -- is not an “agricultural state”, neither the Food Corporation of India nor the state authorities procure the local farmers’ produce.

This forces Delhi’s farmers into distress sale every year --- at prices substantially below the minimum support price set by the Centre.

“The farmers have no bargaining power because there is no official agency procuring our produce. We sell to private mandis, who pay less,” said Debender Singh, a farmer from Nangal Thakran village.