A two-week decline in India’s average daily new coronavirus infections has stirred speculation among experts whether the epidemic has slipped into a decay phase, but they caution that many places across the country are yet to experience peaks.

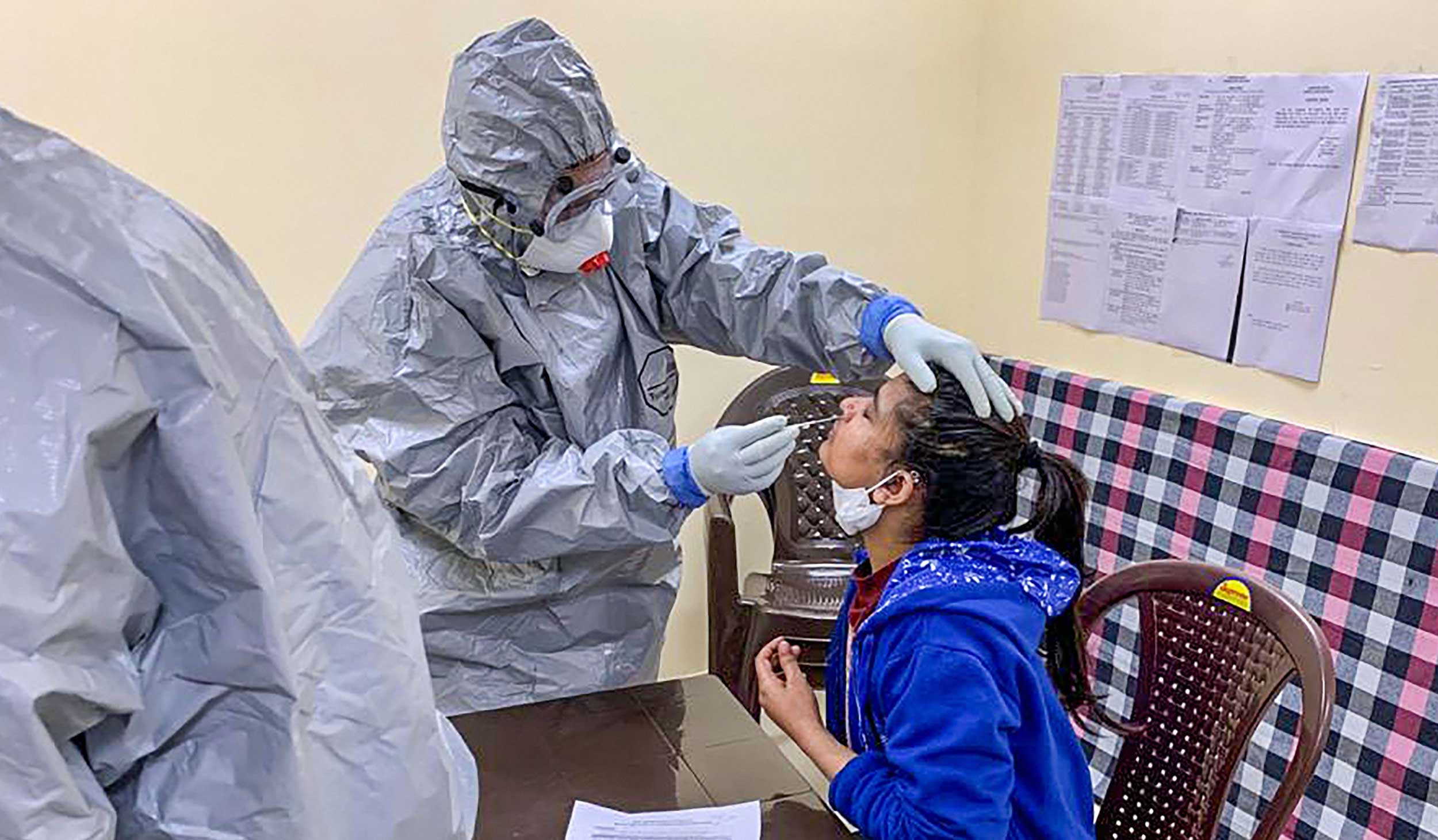

India’s count of coronavirus disease deaths is set to surpass 100,000 on Saturday. But the seven-day average of daily cases detected has fallen from the highest-yet of 93,199 on September 16 to 82,214 on October 1, a decline not observed since the epidemic’s start.

But experts caution that the September 16 peak — if at all — was a nationwide figure that doesn’t help much for a country grappling with different phases of the epidemic in its largest and most densely populated cities, smaller towns and rural areas.

“With an epidemic like this one, an all-India figure may be misleading,” said Jayaprakash Muliyil, a community medicine specialist and member of a Covid-19 epidemiology expert panel set up by the Indian Council of Medical Research.

“It’s something like having one hand in a refrigerator, the other in an oven and saying I’m okay,” Muliyil, former principal of the Christian Medical College, Vellore, told The Telegraph.

The decline in the average daily infections detected has occurred even as the average number of the samples tested daily has increased.

Datasets from the Union health ministry suggest that the average daily tests conducted nationwide increased to around 10.60 lakh during the last three weeks of September compared to around 8.6 lakh during the last three weeks of August.

“Given the steady fall in numbers we’re seeing, I think we can assume the peak is behind us,” said T. Jacob John, an infectious disease specialist and medical virologist also formerly at the CMC. “But the epidemic is still growing at many places — will they change national numbers? We don’t know yet.”

An ICMR survey whose findings where released earlier this week has shown different infection exposure levels in different parts of the country in August — 15 per cent in urban slums, 8 per cent in urban non-slum areas and 4.4 per cent in ruralnareas.

Since then, experts say, the epidemic has grown adding to those proportions. But many caution that there is not enough data yet to determine whether the decline in numbers is an outcome of altered testing strategies.

“The PCR (a genetic test) is the gold standard and reliable, but the numbers of antigen tests (a rapid protein test, an alternative to the PCR) that carry much less reliability have increased in recent weeks,” said Dileep Mavalankar, the director of the Indian Institute of Public Health, Ahmedabad.

“If there is a large shift away from PCR tests to antigen tests, we could get more false negatives and we might see an apparent decline,” Mavalankar told this newspaper.

The Union health ministry has told all states to ensure that every symptomatic patient who is negative on an antigen test gets a confirmatory repeat PCR test. But health officials have expressed concern that this rule is not adhered to uniformly with every patient.

Experts also point out that any testing strategy has a limited role in catching the coronavirus infections given that around 80 per cent of infected people remain asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms.

The ICMR survey findings released earlier this week had suggested that in August, for every reported case, there were up to 32 undocumented infections. The estimated number of infections in August would then have been over 92 million.

Some experts caution that debates over a peak are speculative. “We still do not know enough about this coronavirus to assume when a peak might occur,” said Oommen John, a physician and senior research fellow at The George Institute for Global Health, New Delhi.

“There are reports of reinfections and symptoms lingering for months — could this be due to the persistence of the infection or residual disease or an immune response has not been clearly established?” John said.