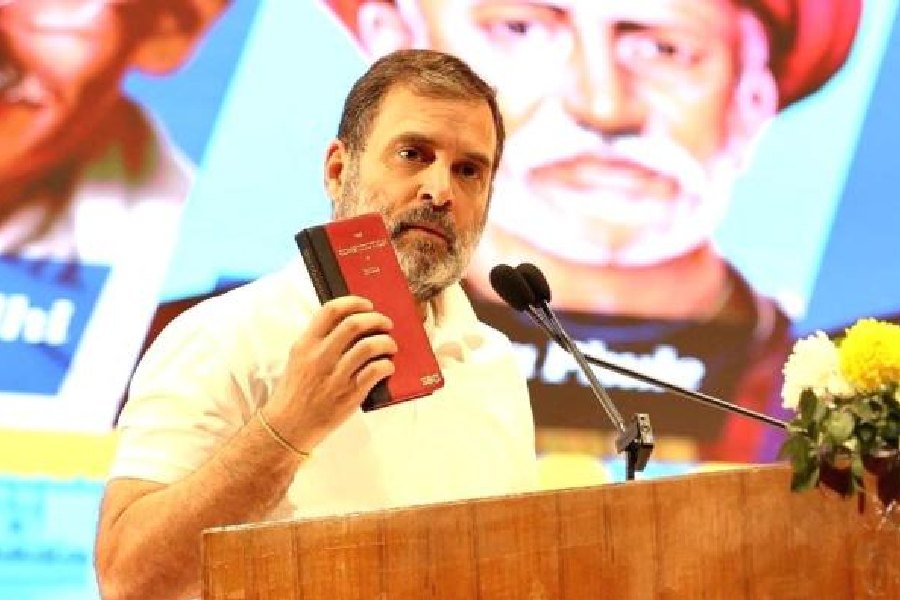

Rahul Gandhi is unlikely to return as Congress president within the next few months and will instead embark on a massive public outreach programme from March-April this year.

Contrary to the general perception and the belief in the party that Rahul had already been persuaded to take over the reins of the Congress, sources close to him told The Telegraph the indications they had got so far was that he is planning tours across the country after Holi, which falls on March 9.

The public outreach plan is clearly aimed at rebuilding the political resistance to Narendra Modi amidst widespread perceptions of a vacuum in the Opposition space.

Most Congress functionaries had started talking with a degree of finality, though in informal conversations, that Rahul would be back as party president by April.

A young aide told this newspaper: “Leaders believe the time is ripe for his return; they think the social unrest caused by the citizenship law and the sustained protests by students should be exploited politically. The students and the civil society brought it this far but the political parties must sustain it now.”

He added: “Rahul is aware of the political responsibilities of the Congress but he does not think this unprecedented crisis calls for his return to the top party post. He believes that the political leadership is required to give voice to the people’s concerns and their insecurities. Parties should articulate the true nature of challenges faced by different sections of society — on the economic and the social front — and hence he will start a nationwide tour (Bharat yatra) at the right time.”

The next stage of the battle will start when the actual process of implementing the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the National Population Register begins; the students and civil society will then need the help of political parties and state governments.

The Congress and other Opposition parties have already demanded the withdrawal of the CAA-NPR and states like Kerala, Bengal, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Maharashtra have positioned themselves for a sustained resistance to the Centre’s push.

If Rahul provides a comprehensive critique of the government — by sewing up the economic and social miseries — and emerges as the voice of the aggrieved people, he would earn a public reasoning for his supremacy in the Opposition camp and validate his return to the post of Congress president.

Quitting the post was his own decision and his aides insist he would not accept any bursting schedule set by the party to ensure that his exit and return don’t look like an orchestrated drama.

Rahul had quit soon after the results of the general election last year but the Congress Working Committee refused to accept his resignation. He finally resisted the party pressure to continue and made his resignation letter public on July 3, compelling the party to explore other options. But there was a feeling that any shock treatment could trigger faster disintegration of the party and hence the safest option of falling back on Sonia Gandhi was exercised.

Sonia, however, has been reluctant to act as anything except a stopgap arrangement; delaying the organisational restructuring and keeping the hopes of a new leader alive. If things work out according to the plan and Rahul succeeds in making an impact during his tours, the party will look at another opportunity sometime around September-October to give him the reins.

The high command and even ordinary workers continue to treat Rahul as the supreme leader but his own hands-off attitude creates complexities on a day-to-day basis. Most leaders feel the leadership question is required to be settled at the earliest as the party’s revival process is directly linked to it. These senior leaders also believe — as do Rahul’s young aides — that relinquishing the post was a mistake but Rahul didn’t heed anybody’s advice.

The contrarian view is that Rahul acted wisely by taking a break as that allowed the people to dispassionately judge the performance of Modi and Amit Shah, without the distraction of the punching bag that he was often used as.

Also, there was no point in continuing the high-pitched political battle during the honeymoon period of Modi’s second term that was ruthlessly cut short because of the reckless execution of the ideological agenda.

Decisions like the abrupt scrapping of key provisions of Article 370 that gave Kashmir its special status and the amendment to the citizenship act created suspicion in the minds of a large section of people that the government was attempting to distort the constitutional scheme.

The economy continued to be in a mess and the use of brute force to crush the expression of dissent inflamed passions across the country. This has considerably weakened the “fear factor” among the ordinary citizens and even political parties will now feel emboldened to confront the government with greater force.

Rahul, who did lead a fierce battle against Modi in 2018-19, has now a fresh opportunity to recall his message that Modi was a failure. The critical difference is that he will have a much greater audience now to lend an ear to his acerbic rhetoric.

The ground reality supports his combative politics much more than what the pre-2019 political climate offered — when the suspicions about Modi’s abilities and intentions were just beginning to sprout.