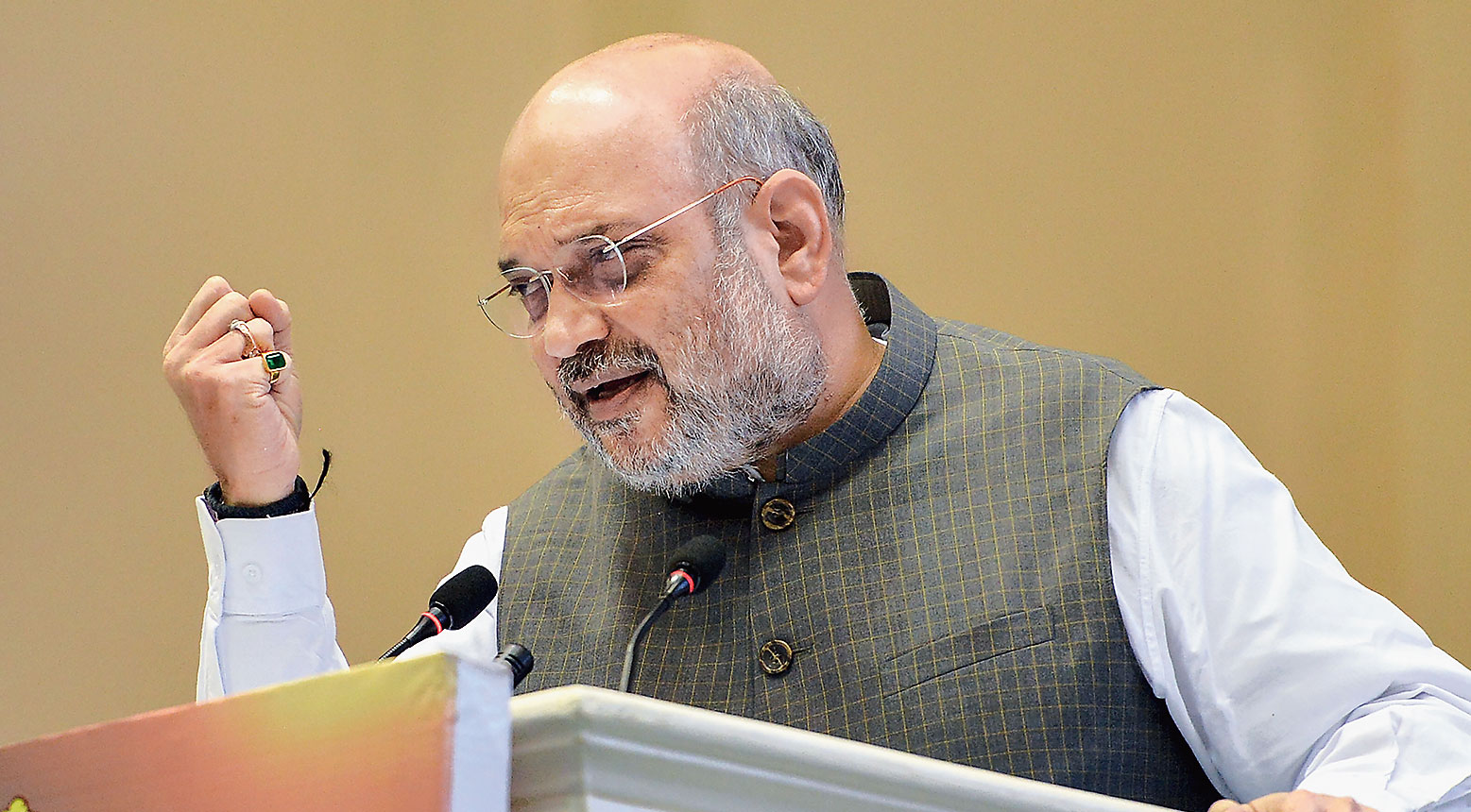

Amit Shah’s clarification about not seeking Hindi’s imposition but only its adoption as a “second language after one’s mother tongue” has divided academics, with many seeing even the toned-down version as a potential threat to state languages and India’s spirit of multiculturalism.

Some language experts said they also wanted to know from the Union home minister what second language he suggested for India’s 43 per cent Hindi speakers.

Chandan Gowda, a professor at the Azim Premji University and a researcher on language politics, underscored that many communities’ mother tongue was not their state language.

Apart from their mother tongue, the children from these communities might well feel a need to learn the state language rather than Hindi as their second language, and English as the third language because it’s the international lingua franca, he argued.

“If they are asked to choose Hindi as their second language, the official state language will lose priority because a section of the state’s population will have no reason to study it,” Gowda said.

He added: “What the home minister said applies only to non-Hindi speakers. He has not specified what the second language should be for Hindi speakers. Will they learn a language from southern or western India or anywhere else outside the Hindi heartland?”

The 8th Schedule of the Constitution mentions 22 languages, including Hindi, according the same status to all of them.

“Hindi is one of the languages in the 8th Schedule. It should not be privileged over the rest. Indians should have a choice which second language they wish to learn,” Gowda said.

Shah had tweeted on September 14 that every language had its importance but it was “extremely necessary to have one language for the whole country that will be India’s identity in the world”.

He had added: “Today, if any one language can do the job of holding the country together with the thread of unity, it is indeed the most widely spoken, Hindi.”

After his statement provoked controversy Shah last week clarified: “I never asked for the imposition of Hindi over other regional languages and had only appealed that one learn Hindi as the second language after one’s mother tongue.”

It’s not clear whether Shah’s reference to “second language” had anything to do with the school curriculum. However, his comment came months after the original draft of the National Education Policy had triggered a controversy by proposing the teaching of three languages across the country’s schools, with Hindi a compulsory subject in Classes VI to X.

When Tamil Nadu and Karnataka erupted in protest, the draft was modified to drop the part on Hindi being compulsory and the ministry clarified that no language would be imposed on any state. Currently, all the states except Tamil Nadu teach three languages in secondary school.

Gowda said it was not at all clear how the lack of a pan-Indian language might undermine the Indian identity globally. On the contrary, he said, India’s ability to sustain a rich cultural diversity was among its most celebrated achievements in the world.

“The idea of ‘one nation, one language, one culture’ is an outdated European idea. At a time when Europe is trying to shed that idea, it is ironic that India, which has always lived with profound cultural diversity, is eyeing a mono-cultural model of the nation,” he said.

“India is a civilisation, not a nation. Making Hindi a language for everyone in the country will be an un-Indian act.”

Ganga Sahay Meena, who teaches Hindi at Jawaharlal Nehru University, said that “technically” he had no problems with Shah’s advocacy of a universal-second-language status for Hindi.

“Today Hindi, not English, serves as the link language among the common people. The minister’s statement is technically fine. But the possibility is that once made the (pan-Indian) second language, Hindi would be pitched for the status of the ‘national language’. The idea of a national language in a diverse country like ours is deeply problematic,” Meena said.

He said Pakistan got divided when it tried to impose Urdu on East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), where the people’s preferred language was their mother tongue, Bangla.

“The RSS believes in one language, one religion, one culture. Every language in India presents a unique culture and knowledge system. The local languages will perish if any particular language is made the national language,” Meena said.

He said some parents in north India had a “feeling of arrogance” about Hindi because it was the most widely spoken language in the country.

He said that while the education policy wanted Hindi-speaking schoolchildren to learn Hindi, English and preferably a south Indian language, their parents got them to learn Sanskrit instead.

“Parents in north India discourage their children from learning south Indian languages because of Hindi chauvinism,” Meena said.

Historian Ramachandra Guha has in his book India After Gandhi quoted then DMK leader C.N. Annadurai to describe the resentment felt in south India during an attempt to declare Hindi the country’s only official language in 1965.

“In Anna’s opinion Hindi was merely a regional language like any other. It had no special merit; in fact, it was less developed than other Indian tongues, less suited to times of rapid advances in science and technology,” the book says.

“To the argument that more Indians spoke Hindi than any other language, Anna sarcastically answered: ‘If we had to accept the principle of numerical superiority while selecting our national bird, the choice would have fallen not on the peacock but on the common crow’.”

Awadesh Kumar Mishra, former director of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, however, agreed with Shah that Hindi had the potential to bind the nation together.

“Hindi does unite people. The structure of Hindi is the same as those of the other Indian languages, except Kashmiri and Khasi,” he said.

“The structure (of a sentence) in English is ‘subject, verb and object’. In Hindi and most Indian languages except Kashmiri and Khasi, the structure is ‘subject, object and verb’. So the common people find it easier to accept Hindi as a link language compared with English.”

He quoted a study by the National Council of Educational Research and Training that said teachers at many schools taught English while conversing with the pupils in an Indian language.

Mishra underlined that Hindi had been made the country’s first official language and English the second, and for 15 years, before the tenure was extended.

He rejected the argument that in India, English today symbolised quality education and people’s aspiration to a fuller participation in national and international life.