Five retired foreign secretaries including a former national security adviser, half-a-dozen directors-general of police, two former central information commissioners, a former chief election commissioner and a large number of retired secretaries to the government all run the risk of being branded “anti-national” today.

Yet, fully conscious of the odds, they chose to stand up and be counted; speaking out in groups of not less than 50 at a time on issues they see as weakening the constitutional framework they swore to protect when they signed up for the civil services, and frequent departures from the rule of law.

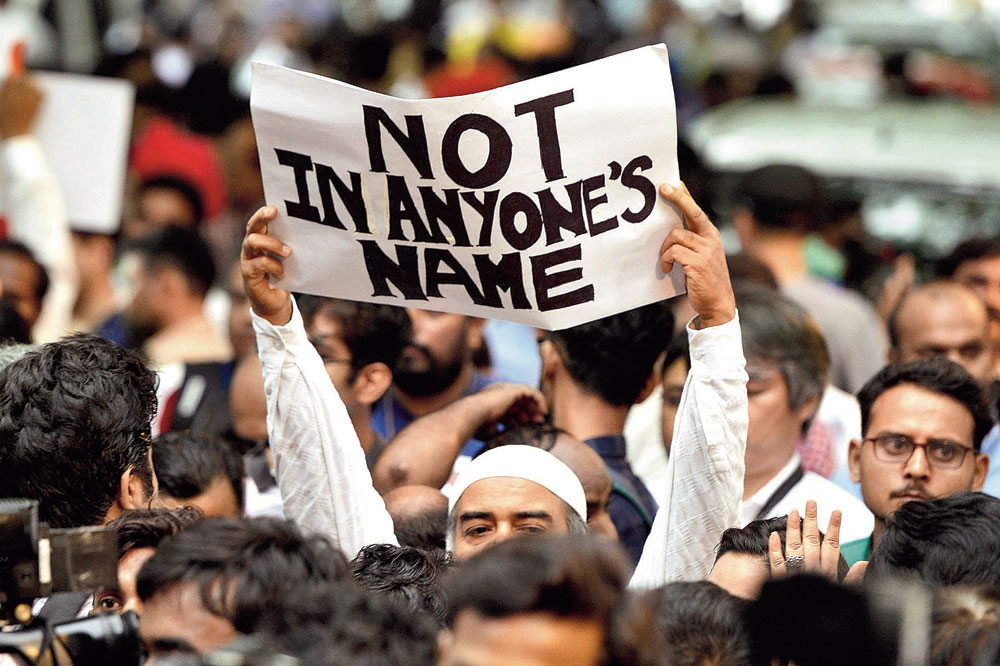

When the collective that now goes by the name Constitutional Conduct first sent out an open letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in June 2017 articulating their deep discontent over religious intolerance — particularly targeting Muslims — and growing vigilantism, they were charting unfamiliar territory.

There is no recall of retired bureaucrats — erstwhile members of India’s steel frame — undertaking such an exercise in the past. “But, our sense of helplessness at what was going on around us was such that we collectively felt that we cannot remain mute witnesses,” said Deb Mukharji, former high commissioner to Bangladesh and one of the early members of the group that is now 157-strong.

Not one of their 15 open letters has got an official response from the government, said Sundar Burra, a former secretary to the government of Maharashtra.

“If this is how interventions of such senior retired bureaucrats are treated, what chance do NGOs and other civil society organisations have in being heard?” asked transparency advocate Anjali Bhardwaj of Satark Nagrik Sangathan.

“This government has followed a policy of complete non-engagement with NGOs. We had problems with previous governments also, but at least we used to get a hearing,” she said.

Apart from non-engagement, other key components of the Modi government’s unstated policy towards NGOs and civil society groups have been to create a chilling effect by using draconian laws like the sedition provision and the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) against activists — such as Sudha Bharadwaj — and the FCRA (Foreign Currency Regulation Act) to tighten the noose on funding of organisations inconvenient to it.

Earlier this year, Greenpeace announced that it has had to shut down two of its regional offices — in Delhi and Patna — and lay off 40 staff members due to lack of funds as it was barred from receiving foreign donations from 2015 onwards and its bank account frozen subsequently.

The impact is such that even Indians who may be inclined to fund these organisations think twice before doing so for fear of government reprisals; something that even Opposition parties talk about as they are forced to fight the cash-flushed election juggernaut of the BJP with peanuts in comparison.

Yet, civil society has been chugging along in their attempt at reclaiming the idea of India as envisaged in the Constitution. Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP), which is battling several court cases of its own, has set up a hate-watch app to track hate speeches and make interventions.

According to Teesta Setalvad of the CJP, the purpose is to build a community of people who are agitated by hate and provide the back-up to intervene. “Hate speech tends to paralyse people and we want to tell them that action can be taken. Where they don’t want to follow it up with the nodal agencies where the complaints can be lodged, we do it for them and pursue these cases,” she said.

Essentially for all who are standing up in their own ways, silence is not an option. Over the past fortnight, concerned citizens have been grouping themselves as per their trade or art form with just one message: Save the Constitution, reclaim the space that modern India has allowed for dissent and differences, and vote out the politics of hate.

This was also evident last Saturday at Delhi’s Talkatora stadium where over 200 different campaigns, representing the spectrum of social and people’s movements — employment, pension, health, education, forest and tribal rights, Dalit, women, minority rights, civil liberties and democratic rights — converged to draw up a “Jan Sarokar” or people’s agenda.

“These elections are not ordinary. It will decide whether our country and the values that we cherish will survive. Our fight for rights will continue whichever government comes in, but right now we have to stop the assault on India’s soul,” the CPI(ML)’s Kavita Krishnan said.

She quoted German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht: “Insaaf janta ki roti hai (justice is the bread of the people)”.