The Supreme Court on Wednesday granted bail to former finance minister P. Chidambaram in a case of alleged corruption, reaffirming the well-established principle that bail is the rule and its refusal an exception.

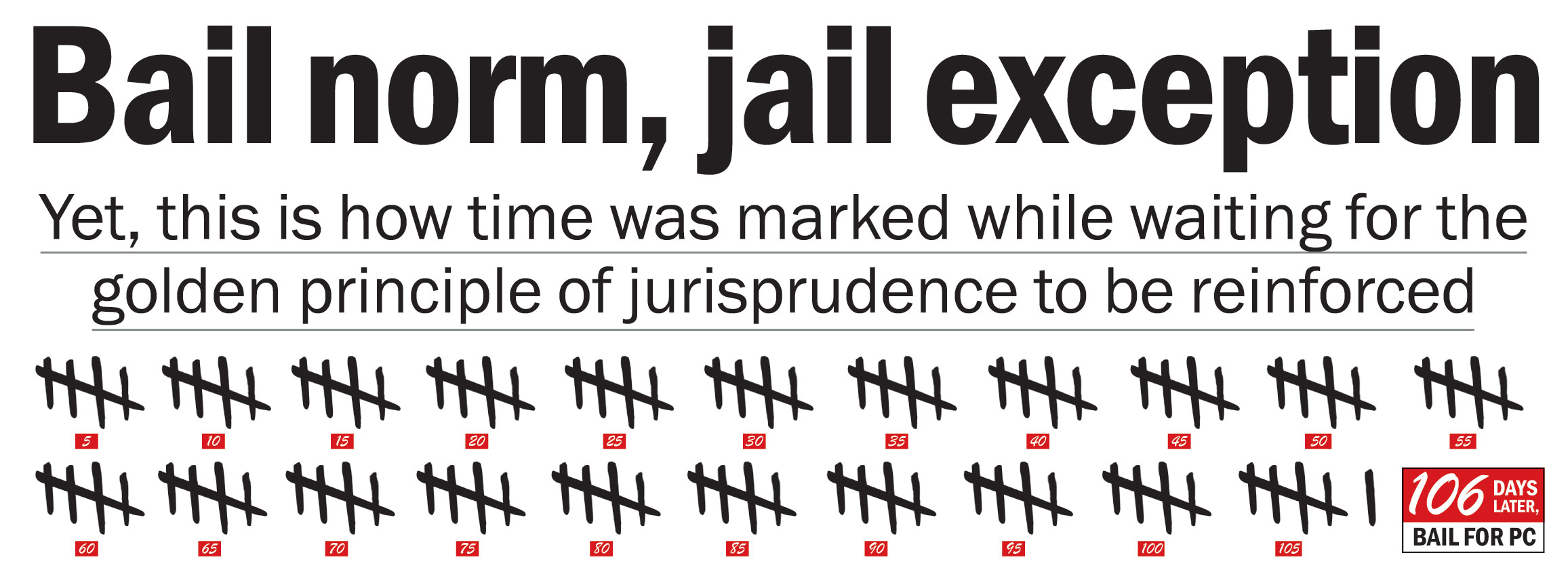

Chidambaram was freed on Wednesday evening after spending 106 days in custody in the INX Media case in which he is accused of flouting norms while clearing foreign investments in excess of the prescribed limit in 2007 when he was finance minister. The Congress leader now faces trial in the case.

While setting several conditions for bail, the court said Chidambaram must not give any media interviews, nor make any public comment in connection with the case.

Chidambaram’s imprisonment for such a long period, even before any court had convicted him, had triggered widespread concern but not many had dared to speak out. Last week, veteran industrialist Rahul Bajaj had publicly raised the issue in front of home minister Amit Shah at an awards event in Mumbai.

While granting bail to Chidambaram, the Supreme Court rejected the Enforcement Directorate’s assertion that a stricter view should be taken as the charges were grave. The court also took into consideration Chidambaram’s age (74), his ailments and the release of other accused in the case.

Chidambaram was arrested by the CBI on August 21, with agency officers scaling the walls of his Delhi home past midnight.

(Telegraph)

Some of the key observations made by the bench of Justices R. Banumathi, A.S. Bopanna and Hrishikesh Roy in the bail order:

⚫ The basic jurisprudence remained that the grant of bail was the rule and refusal an exception to ensure that the accused has the opportunity of securing a fair trial.

⚫ However, while considering bail, the gravity of the offence should be kept in mind.

⚫ Even if the allegation is one of grave economic offence, it is not a rule that bail should be denied in every such case since the relevant enactment creates no such bar, nor does bail jurisprudence.

⚫ The “underlining conclusion is that irrespective of the nature and gravity of charge, the precedent of another case alone will not be the basis for either grant or refusal of bail though it may have a bearing on principle.

But ultimately the consideration will have to be on a case to case basis on the facts involved and securing the presence of the accused to stand trial.”

⚫ Courts may peruse materials placed in sealed cover during bail hearings but comments that can have a bearing on the main trial should be avoided, especially if the suspect has passed the “triple test” for the grant of bail that the apex court had fixed in earlier cases. (The Supreme Court said it did not want to read the content in the sealed cover but had done so only because it had already been perused by a Delhi High Court judge and the matter was under challenge.)

Under “the triple test” doctrine, an accused can be granted bail if it can be established that he or she is not a flight risk, will not influence witnesses and will not tamper with the evidence. Chidambaram had fulfilled the criteria.

⚫ There was no material to indicate that Chidambaram or anyone on his behalf had “restrained or threatened” a witness who had refused to be confronted with him during the probe.

The Supreme Court ticked off Delhi High Court for the adverse observations it had recorded against Chidambaram on the basis of certain materials placed by the ED in a sealed cover while denying him bail on November 15. The apex court said the high court’s observations on a sealed-cover report would cause prejudice to the accused during the trial.