Chest X-rays on young and middle-aged adults with the new coronavirus disease, performed on entry into hospitals, may be faster predictors than blood biochemistry of who might be at high risk of severe disease, US doctors said on Thursday.

Doctors from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York said their study was the first to examine how emergency room chest X-rays could be used to evaluate disease in the lungs and predict patients’ outcomes.

The Mount Sinai doctors have shown that specific patterns of patches on X-ray images can be assigned scores – the higher the score, the higher the patient’s risk of severe disease.

Their findings, published in the medical journal Radiology on Thursday, may help physicians quickly identify, triage and aggressively treat the patients assessed to be at high risk of developing severe disease.

While critical care specialists are already assigning scores to assess patients’ risk, using blood biochemistry readings — including a clotting-linked protein called d-dimer — and organ functions, the New York doctors believe that scores based on chest X-rays provide advantages.

“The chest X-ray is quick and seems to correlate better to patients’ status than blood biochemistry and certainly more than d-dimer, which is elevated in almost all hospitalised patients with any (serious) disease,” Danielle Toussie, radiology resident at the Icahn School, told The Telegraph.

Chest X-rays look for opacities — patches— in the lungs that are indicators of disease. Toussie and her colleagues noted that while most patients had disease in the lower lobes, the patients who had multiple areas of disease, or disease in the upper lobes, seemed to be doing worse.

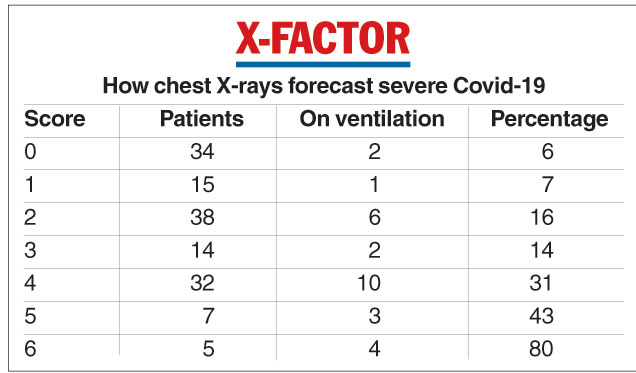

They developed a scoring system based on opacities and observed the progress of a set of 338 patients, among whom 145 had been admitted to hospital. Scores of zero to 2 appeared associated with low severity and scores of 3 to 6 with high severity.

The study found that the higher the scores, the higher the probability of the patients requiring ventilation.

For instance, 2 of 34 patients (6 per cent) with a score of zero needed ventilation, 2 of 14 patients (14 per cent) with a score of 3 needed ventilation, and 4 of 5 patients (80 per cent) with a score of 6 needed ventilation.

“It is no surprise the chest X-rays correlate well with severity of disease — after all, this is a primary respiratory illness, a pneumonia in the lungs,” Toussie said. “But it is one thing to think about it and another to prove it with evidence.”

The Icahn School group is now looking at the predictive value of repeated follow-up chest X-ray examinations and the possible correlations between patterns of opacities and blood biochemistry readings.

“All this will add to our ability to look at chest X-rays in Covid-19 patients and tell what is likely to happen,” Toussie said.