Chauri Chaura is a small town not far from Gorakhpur in eastern Uttar Pradesh. But for a violent incident 99 years ago during the Non-Cooperation Movement, this place which was then a village would probably have remained unknown.

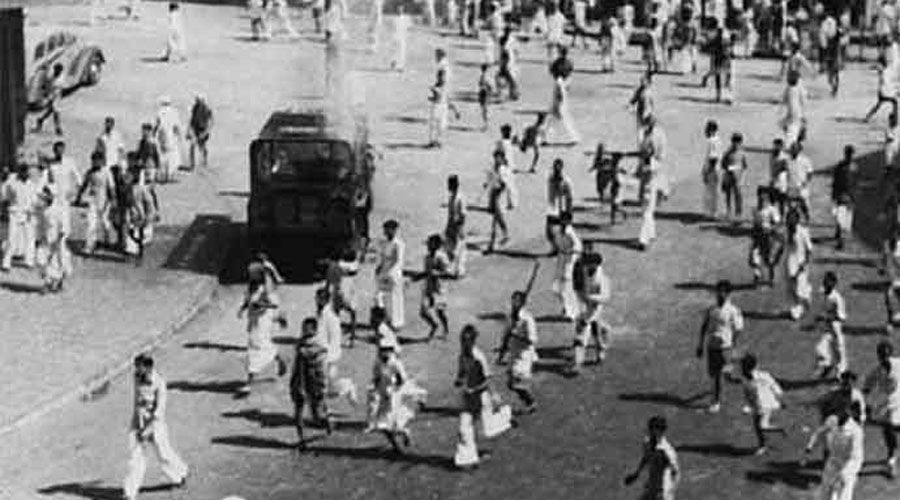

On February 4, 1922, a mob of 3,000 freedom fighters set fire to the police station in Chauri Chaura killing 26 policemen, including an inspector. This was the third instance of violence during the movement launched by Mahatma Gandhi a year previously, after two smaller incidents had been reported from Bombay and Madras.

The Chauri Chaura violence was the last straw for the apostle of non-violence. He immediately summoned a meeting of those Congress Working Committee members who were not in jail and asked them to pass a resolution suspending the movement.

This sudden suspension was deeply resented by many in the Congress, especially the younger leadership. Jawaharlal Nehru, then 32 years old and imprisoned in Allahabad along with his father Motilal Nehru, received the news with “amazement and consternation”.

“We were angry when we learnt of the stoppage of our struggle at a time when we seemed to be consolidating our position and advancing on all fronts,” Jawaharlal wrote in his autobiography.

Subhas Chandra Bose wrote: “To sound the order of retreat just when public enthusiasm was reaching the boiling point was nothing short of calamity. The principal lieutenants of the Mahatma, Deshbandhu (Chittaranjan) Das, Pandit Motilal Nehru and Lala Lajpat Rai, who were all in prison, shared the popular resentment.”

The withdrawal of the movement and the differences among the top leaders of the Congress misled the imperial government into thinking that the Mahatma’s influence was on the wane and that it was time to act against him.

Gandhi was arrested on the charge of sedition and sentenced to six years’ imprisonment. But the importance of Chauri Chaura can only be understood if we recall the events that led to it.

The brutal Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 and the findings of the Hunter Committee that looked into the incident had shattered Gandhi’s faith in the British sense of justice. Besides, the end of the First World War had witnessed the dismemberment of the Khilafat (Caliphate).

The Mahatma prevailed on the Congress to adopt as India’s national demands the redress of the triple wrong of the Rowlatt Bills (which allowed indefinite imprisonment without trial, among other things), Jallianwala Bagh and Khilafat.

He concluded that the old methods had to be given up and decided to launch the Non-Cooperation Movement. A special session of the Congress was called in Calcutta in September 1920 and was presided over by Lala Lajpat Rai, who had recently returned from the United States.

Here, the Mahatma himself moved the resolution on non-cooperation. He was opposed by not only Rai but other stalwarts like Bipin Chandra Pal, Chittaranjan Das and Madan Mohan Malaviya. Motilal Nehru not only supported Gandhi but mobilised support for the resolution among the delegates.

After a long and heated discussion, the resolution on “non-violent non-cooperation” was adopted. It asked for the surrender of titles, resignation from nominated seats in the local bodies, and boycott of the law courts, government schools and colleges and all official functions.

Further, the people were asked to boycott foreign goods, promote swadeshi (goods made in India) and work for the establishment of swaraj (self-government).

This opened a new chapter in the nation’s history. The days of “prayer, petition and protests” were over, according to Acharya Kripalani, an early associate and biographer of Gandhi, who would become Congress president on the eve of Independence.

The resolution on non-cooperation and constructive work passed by the special session had to be ratified at a regular plenary session that was held in Nagpur three months later.

Here the top leaders of the Congress who had opposed Gandhi in Calcutta fell in line and fully supported him: the resolution was moved by Das and seconded by Rai.

The Nagpur session was a turning point in the history of the freedom struggle, with the Mahatma emerging as the unquestioned leader of the independence movement.

Motilal, who had renounced his lucrative legal practice immediately after the Calcutta session, was now joined by Das who too gave up his huge practice at the Bar. They inspired many others to give up their comfortable lifestyles and adopt austerity, simplicity and khadi.

The people’s response throughout the country was overwhelming. Lawyers gave up their practice; teachers and students left government schools and colleges. Many new national schools, colleges and vidyapeeths opened in urban and rural areas.

A Tilak Swaraj Fund was set up in memory of Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who had died on the eve of the Calcutta session, with the objective of raising Rs 1 crore, a huge sum those days. The target was exceeded.

The enthusiastic popular response caused a jittery government to resort to a policy of extreme repression. When the Prince of Wales arrived in India in November 1921 and was greeted by a complete hartal and bonfires of foreign clothes, the government retaliated by arresting all the key leaders.

Nearly 20,000 civil resisters were in jail by the end of the year. The atmosphere in the country was tense but the people were ready for any sacrifice.

The Mahatma was preparing to launch a mass civil disobedience programme in Bardoli, Gujarat, when reports of the Chauri Chaura violence reached him.

The leaders who had criticised Gandhi for suspending the movement later realised that he had taken the right decision.

Jawaharlal wrote a decade later: “There is little doubt if the movement had continued there would have been growing sporadic violence in many places. This would have been crushed by the government in a bloody manner and a reign of terror established which would have thoroughly demoralised the people. These were probably the reasons and influences that worked in Gandhiji’s mind, and granting his premises and the desirability of carrying on with the technique of non-violence, his decision was right.”

As a result of the Non-cooperation Movement, the Congress became a mass movement that created an awakening among millions of people to become participants in the struggle for independence regardless of the torturous road ahead.

It is therefore not Chauri Chaura but the whole Non-cooperation Movement that needs to be celebrated. It was this movement that set us on the right path to freedom.

- The author is a former army officer and a former member of the National Commission for Minorities