The BJP ecosystem’s use of “Sanatani” to refer to all Hindus finds no support in the writings of B.R. Ambedkar or the NCERT’s Class X history textbook, which describes Sanatanis as “conservative high-caste Hindus”.

In Ambedkar’s view, the term “Sanatan (or Sanatana) Dharma” — now being used by the BJP and its supporters as a synonym for the Hindu religion — denotes only Vedic and Brahminical traditions, and is derived from the description of the Vedas as “Sanatan” (eternal).

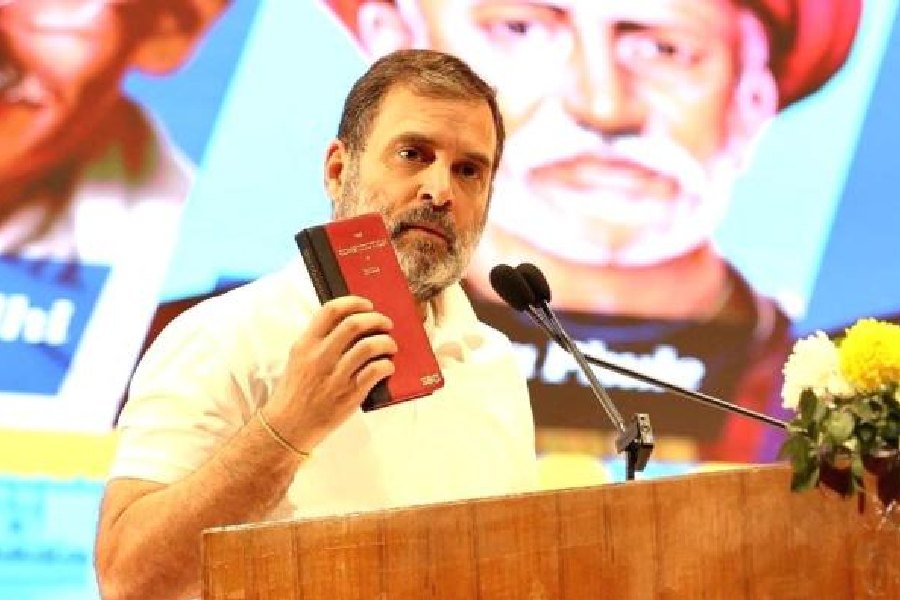

The issue has exploded into the national political stage following a call from Tamil Nadu minister Udhayanidhi Stalin to “eradicate” Sanatana Dharma because it creates divisions among people. The BJP has interpreted this as a call for “genocide of 80 per cent population of Bharat who follow Sanatana Dharama” — a charge denied by Udhayanidhi.

Two historians this newspaper spoke to corroborated the positions of Ambedkar and Udhayanidhi by asserting that “Sanatana Dharma” originally referred not to any religion per se but to a set of “eternal” duties or moral principles for everyone to follow, depending on their station in life or caste.

Later, when the term took on a religious connotation about a century and a half ago, they said, its denotation was restricted to Brahminical traditions and practices.

In his book Riddles in Hinduism, Ambedkar quoted from Kalluka Bhatt’s commentary on the Manusmriti to say that the term “Sanatan” was originally used to assert the “eternal” pre-existence of the Vedas and the unchanging nature of the knowledge and precepts they contain. Brahmins later extrapolated the word to denote the Hindu civilisation.

“If the question was addressed to a Vedic Brahmin he would say that the Vedas are Sanatan,” Ambedkar wrote.

The chapter “Nationalism in India” in the NCERT’s Class X history book, India and the Contemporary World-II, says in the context of the Non-Cooperation and Civil Disobedience movements: “Not all social groups were moved by the abstract concept of swaraj. One such group was the nation’s ‘untouchables’, who from around the 1930s had begun to call themselves dalit or oppressed.”

It adds: “For long the Congress had ignored the dalits, for fear of offending the sanatanis, the conservative high-caste Hindus.”

A history professor who would not be quoted said the term “Sanatana Dharma”, which originally meant a set of ethical tenets, began to be associated with religious belief and practices around the time Swamy Dayananda Saraswati founded the Arya Samaj in 1875 to oppose ritualistic Brahminic traditions, child marriage, untouchability and the denial of education to women.

“A section of people, particularly the Brahmins, opposed the reforms movement saying it was against the Sanatana Dharma, making the Brahminical connotations of the term clear,” he said.

The academic said that Udhayanidhi was therefore justified in attacking Sanatana Dharma as a means of targeting Brahminical practices.

Udhayanidhi has clarified on X, previously Twitter, that he never called for genocide of people who follow Sanatana Dharma and underlined that Sanatana Dharma is a principle that divides people in the name of caste and religion.

Pankaj Jha, a faculty member of history at Lady Shri Ram College, said Uttararamacharita by the eighth-century poet Bhavabhuti and Bhattikavya by the seventh-century poet Bhatti used the term “sanatana” to imply that dharma is unchanging and firm.

“In both texts, ‘dharma’ meant a set of obligations or duties. Dharma could differ from person to person depending on one’s social position, status and station in life: hence the use of terms such as Putradharma (duties of a son), Gurudharma (duties of a preceptor), Rajdharma (duties of a ruler), and so on.

“Vedic traditions defined ‘dharma’ as righteousness, that is, actions appropriate to holding up social life and social order. In that context, if you say dharma is sanatana, it means that righteousness is unchanging.”

However, Jha said, the Sanskrit literary tradition is not singular and certain texts provide other ways of looking at dharma.

“For example, the whole idea of Yugadharma (values appropriate to the age one lives in) presumes that dharma is changing and not frozen,” he said.

“The use of the term ‘Sanatana Dharma’ to mean Hinduism is a recent phenomenon, probably no older than 150 years. It might not be wrong to say that only a certain conservative line of Hinduism was referred to as ‘Sanatana Dharma’ in the late 19th and 20th centuries.”

Jha cited the wide regional variations in Hindu practices, and the “multifarious and dynamic history of Hinduism” to question the concept of it as “Sanatan”.

“Like all religions, this religion also claims to be timeless. And like all religions, it too has a beginning, spread and development through time,” he said.

Jha added: “Udhayanidhi’s statement seeks to distinguish the Hindu religion from the Sanatana Dharma. His comments appear rhetorical, anyway, and if you read ‘Sanatana Dharma’ in its original sense, then he did not call for destroying Hinduism.

“Remember, Varnashramadharma, the obligations appropriate to one’s Varna, was seen as the core of Sanatana Dharma. And Varna is the core principle on which caste discrimination is based. Hence, to call for destroying ‘Sanatana Dharma’ can also be seen as a call to destroy the basis of the caste system.”

Ambedkar too wrote that the Hindu religion teaches not fraternity but division of society.

“The Hindu social system is undemocratic not by accident. It is designed to be undemocratic. Its division into varnas and of castes and outcastes are not theory but are decrees,” he wrote in Riddles in Hinduism.

Ambedkar countered the claim of “eternality” of Hindu practices by highlighting how they had changed over time. He cited Tantra worship, which not only lifted the prohibition imposed by Manu on liquor and meat but turned drinking and meat-eating into articles of faith.