The NDA scraped past a breathtaking challenge by the Tejashwi-led Mahagathbandhan to retain a skin-thin hold on power in Bihar on an extended see-saw day that saw chief minister Nitish Kumar downgraded and the state’s political polarities defined between the BJP and the RJD that emerged the single-largest party.

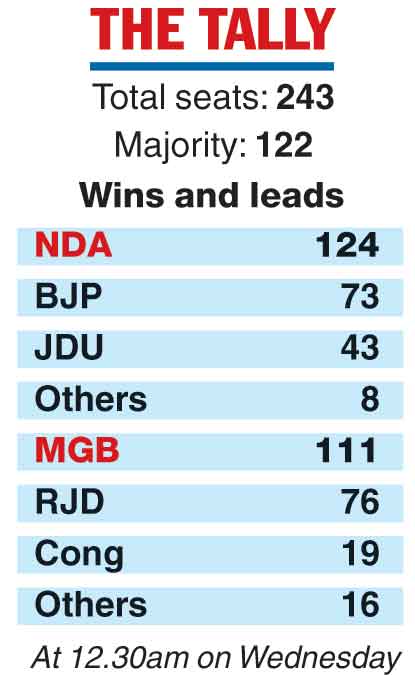

Amid bitter neck-and-neck battling, the RJD claimed late evening that 119 Gathbandhan candidates had won and accused the state administration of declining victory certificates to some after they had been declared winners by returning officers. The bare majority mark in the 243-member Assembly is 122.

RJD MP Manoj Jha, one of the party’s chief strategists, said late on Tuesday night that he had been assured by the Election Commission of fair redress.

“We trust the Election Commission (EC), we do not trust the state administration,” Jha said. “We are assured that the voice of the people, as reflected by the campaign, will triumph, Nitish Kumar’s efforts to hang on to the chair by hook or by crook will be defeated.”

Jha alleged pointedly that Nitish’s chief ministerial office was being “used to unfairly influence the result on at least two dozen seats” through pliant bureaucrats. The NDA retaliated, saying the RJD was carping because it knew it had “lost the election”.

The Election Commission, on its part, rebuffed the RJD’s specific allegations but indicated that recounts may be required on some seats, leaving a clear verdict in the balance.

Early evening, the BJP headquarters in Delhi was in ecstatic throes over the impending arrival of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, home minister Amit Shah and party chief J.P. Nadda to mark victory.

But the rites were swiftly aborted as it became apparent that the NDA’s victory was far from certain. The faithful were instructed to lower the celebratory decibel and disband.

Nobody could be sure which way the verdict would turn. Close to midnight, though, the BJP officially claimed victory for the NDA ahead of the formal declaration of results.

The takeaways

The results have already pronounced a few things worthy of note.

The BJP, by far the stronger NDA party now, has snatched the baton from Nitish who must now play beholden and compliant chief minister should he be given the job he has publicly been promised.

Tejashwi has ensured that Bihar has an ebullient Opposition in the RJD and its partners. He came tantalizingly close to snatching power, but was pipped at the post by a combination of factors that include a significant counter-consolidation of votes to arrest his surge to the top office.

The late swell in NDA votes — a consequence of widespread perception that Tejashwi might wrest power — is evident from the fact that the NDA, and the BJP in particular, did far better in the second and third rounds of polling; the first was domineered by the Gathbandhan, word went out, and the BJP resorted to remedy losses.

Critical to that effort was proactive rekindling of fears of the return of “jungle raj” towards the latter half of the campaign and Prime Minister Modi played chief drumbeater of apprehension.

Forever keen on Bihar, Modi spearheaded the NDA campaign with recurrent visits and multiple rallies where he performed his trademark act of stoking bogey apprehensions about the Opposition and resorting to nakedly sectarian entreaty woven around the Ram temple and the invocation of Bharat Mata.

There was more at stake for the BJP than just loss of power in Bihar. The message from a reverse in a heartland state tends to resonate beyond its physical boundaries; with polls impending in neighbouring Bengal, a state the BJP desperately wants to wrest from the Trinamul Congress, losing Bihar would trigger unhelpful ripples.

What looked like a romp for the NDA at the beginning of the campaign became a tricky uphill towards the end essentially because Tejashwi surprised adversaries and allies alike with a stirring turn at the hustings.

Only a day older than 31, Tejashwi was able to rally his troops and Gathbandhan forces remarkably in the absence of the RJD patriarch Lalu Prasad.

Tejashwi foregrounded unemployment and economic stress as key issues, and appealed to all sections of Bihar as opposed to his party’s traditional Mandal-Minority theme.

His battlefront performance was no less outstanding for the fact that he put a veteran like Nitish in the shade and was duelling single-handed against none other than Prime Minister Modi, the lead NDA campaigner.

The Gathbandhan’s performance was buoyed in good measure by Left parties which led on 18 of the 29 seats they contested but dragged down by the Congress, which hogged a 70-seat share but returned less than a third. RJD leaders had conceded privately through the campaign that they had given away far too many seats to the Congress.

Ahead of the campaign, odds were stacked overwhelmingly in favour of the NDA, many willing to bet it would be a one-way race; Tejashwi was dismissed as a rookie incapable of posing a credible challenge to the formidable arithmetic and resources of the NDA.

The RJD scion, though, made a battling fist of it with a campaign that was not only electric of energy but also well-meditated and focused. Its fundamental theme was to upgrade the RJD talisman of social justice to the quest for economic justice, a call that resonated across the battleground and brought an exuberance to Tejashwi’s election outings that was reminiscent of Lalu at his peak.

A key element of the RJD campaign was also to studiously skirt default traps set by the BJP to buttonhole opponents as “minority rights champions” and create polarisation along sectarian lines.

The RJD had won 80 seats in the 2015 Assembly polls in alliance with Nitish Kumar and the Congress; that Tejashwi has run his party to sniffing distance of that number and emerged as the single-largest formation in Bihar without Nitish is a sign of how stunning his dare has been.

By contrast, Nitish stands drastically diminished as a leader and his JDU relegated to a distant third on the rostrum. The campaign was peppered by signs of his growing unpopularity; electorally, he was probably hurt by the widespread perception that part of the BJP’s objective was to reduce him in stature and size.

The free rein given to LJP’s Chirag Paswan to openly challenge and contest Nitish while he remained an NDA ally was a sign he was playing trojan horse at the BJP’s bidding.

Nitish might yet become chief minister, as the BJP has publicly promised, but with his reduced numbers he has been hollowed out and will keep office at the mercy of his altogether larger ally.

Tejashwi, on the other hand, may have suffered the consequences of being perceived leader of the Bihar race in the latter half of the campaign. Paradoxical as it sounds, the more the RJD seemed close to hitting the tape, the more consolidation it caused of adversarial votes.

The spectre of “Lalu raj” remains psychologically troublesome for fair sections of voters, especially upper castes and elderly voters who retain deep and unsavoury memories of the disorder that attended most of the 15-year Lalu reign from 1990-2005.

In addition, Asaduddin Owaisi’s AIMIM appears to have made significant inroads into the RJD’s ambitions in the Muslim-preponderent Seemanchal belt verging on West Bengal.

Leading on a record five seats — their debut in the Bihar assembly — Owaisi’s candidates split and snatched minority votes whose default choice would have been the Tejashwi-led Gathbandhan.