Jodi tor daak sune keu na aashe,Tobe ekla chalo re.

Jodi keu katha na koy, Jodi sobai thaake mukh phiraye,Sobai kore bhoy, Tobe poran khule,

O tui mukh phute tor moner kathaEkla bolo re.

(If no one answers your call, Walk alone. If no one speaks to you, If everyone turns away, If everyone is afraid to speak, Then with an open heart, Without hesitation, Speak alone.) — Rabindranath Tagore

At the Khalsa Ground in Mandi Gobindgarh where the Bharat Jodo Yatra had stopped for lunch on its first day in Punjab, a cheerful-looking woman in a printed salwar suit, cardigan and woollen cap emerged from the langar tent, wiping her mouth with a handkerchief.

Are you a local, I asked, curious because she did not look like a political worker. “Yes, from Shastri Nagar,” she responded.

She was on the ground because the Yatra that had started from Kanyakumari on September 7 had walked all the way to her hometown on January 11 and she thought she should be there.

“The gents say they are busy. So I thought I would come. Can we not even do this much?” she asked.

She came alone but had made a friend — the other woman was also a resident of Mandi Gobindgarh who had come on her own initiative.

The Yatra was going to start for the second leg of the day at 3.30pm. We had hoped to catch it arriving into the steel town at 11.20am but had failed. Daunted by the biting cold of Punjab’s winter and the risk of driving in the fog before daybreak, we did not join at Fatehgarh Sahib from where the Yatris had begun their walk through the state in the morning.

Rahul Gandhi had flown to Amritsar the previous day to pay his respects at the Golden Temple, Sikhism’s central place of worship whose storming by the Indian Army in 1984 had been the trigger for the assassination of his grandmother and then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Operation Bluestar and the anti-Sikh riots that followed the assassination had alienated a large section of the community from his family and the Congress.

Fatehgarh Sahib has deep emotional resonance for Sikhs. It is the site where Fateh Singh, 6, and Zorawar Singh, 9, the two younger sons of the tenth guru, Guru Gobind Singh, had sacrificed their lives. The wall in which the Chhote Sahibzaade were bricked in alive when they refused to change their faith can be seen inside a gurdwara that stands there today.

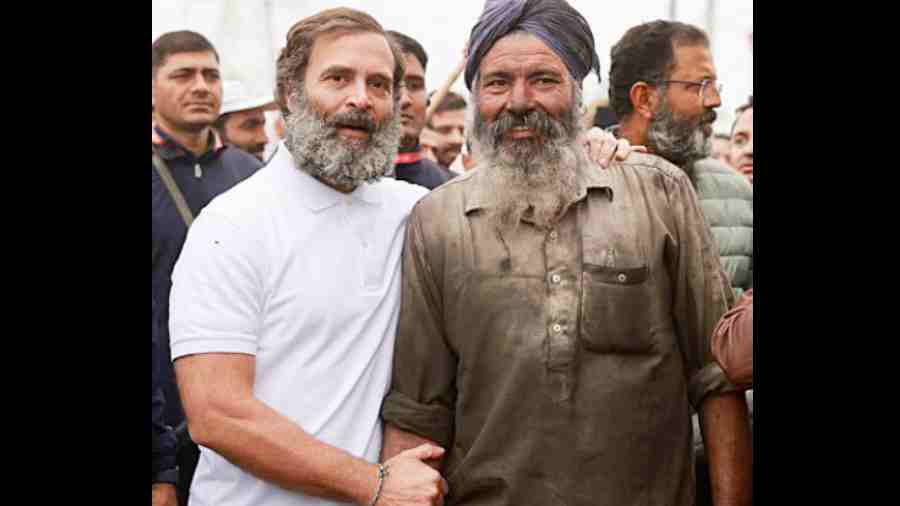

Rahul Gandhi with a factory worker during the Yatra in Punjab on January 11 Sourced by The Telegraph

Gurdwara Shri Fatehgarh Sahib is where Rahul started his journey in Punjab from, at 7am.

Our plan was to drive straight to Khalsa Ground in Gobindgarh and wait for the Yatris to troop in after their morning leg. We would walk with them in the afternoon when they started for Khanna in Ludhiana district, the Yatra’s first night halt in the border state that would be its last stop before it entered Jammu and Kashmir.

We arrived a good hour late, taking 3 hours to cover the over 50km distance from Chandigarh that should take an hour and a half. The reason: our cab driver who had voiced such concern about the Yatra disrupting traffic and delaying people on their way to catch flights had not bothered to check the road it was taking and ended up behind it

As we scanned Google Maps to see if there was any way we could get on another route now, he got out of the cab and went around mockingly telling truck drivers stuck in the jam: “Rahul Gandhi is walking, so you had better get out and walk too. Join his Bharat Jodo Abhiyan.” Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. Like Swachh Bharat Abhiyan.

Khalsa Ground, located on a road parallel to NH44, wore a festive look. A large banner at a gate said: “State Yatris.” A lot of people were milling around outside, many with Congress identity cards hanging around their necks and some wearing white Yatra T-shirts and caps.

Youth Congress volunteers helped us get inside Gate 2, the one that was marked “State Yatris”. In one expansive tent, people rested on mattresses laid out on the ground, wrapped in blankets. In the next tent, lunch was being served. Most people around were Congress workers. A group of scruffily dressed teens with spiky hair stood near a cloth-covered barrier that separated the enclosure from that for the Bharat Yatris.

Possibly, like a group of Congressmen and women who too were stationed there looking in the same direction, they were hoping to catch sight of Rahul. “He should come around and meet the workers too, shouldn’t he?” asked one discontented young woman in a long coat who said she was a local Congress worker.

There was a hubbub as a leader appeared to be approaching from the other side. Between the two enclosures was no man’s land. Amarinder Singh Warring, the tall state Congress president in pink turban, addressed the Punjab workers, urging them to put their best foot forward, be hospitable and welcoming, and not complain about the food at the langar, while asking for forgiveness if anything was not up to the mark.

As we were surveying the crowd, the bearded young man who had ushered us in and whose ID card gave his name as Shesh Narayan Ojha appeared. “Please have lunch,” he said. As we thanked him and shook our heads, he insisted: “Please come. Lunch is for everyone and it is good.” Hot rajma and rice, paneer and dal and roti and halwa and salad were being served from clean buffet tables covered in white tablecloth.

Round tables with chairs were occupied by all manner of people — some children and women but mostly men, some dressed carefully, others whose poverty you could tell by their clothes. There was a large group of lean young men in navy blue tracksuits that had “PRTC Jahan Khelan” emblazoned on their backs in yellow. We would know in a bit the crucial role they played.

A bell rang, shrill like the school bell. It was past 2. Some people had begun to walk out of Gate 2, in ones and twos. The bell rang again. The Yatris were getting up and preparing to leave. We decided to go out and wait. Some people were walking down the road in the direction of Ludhiana — Khanna is about 40km east of the city founded in the time of the Lodhi dynasty that is now known for its cotton and woollen garment manufacturing industry and the large number of Mercedes sold.

On the highway above, there was a policeman with a gun aimed at our road. A police vehicle drove up and down in an effort to keep the ever-growing crowd on both sides from spilling onto the carriageway. The men in white Yatra T-shirts and caps had formed a ring around a vehicle with cameras and crew — it must be the one that has been beaming the live feed of the walk — and started running as the vehicle began to move.

All of a sudden, the young men in blue we had seen in the langar tent appeared in sight, running. They were holding a rope that formed a ring. We learnt later that PRTC stands for Police Recruits Training Centre and Jahan Khelan is the place in Hoshiarpur district where the establishment set up in 1947 is located. Inside the ring — which everyone was calling the D — was a small crowd of people walking briskly.

“Rahul Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi,” a roar went up. “There he is,” someone shouted and necks craned. The white T-shirt that has drawn more media attention than the fact of more than 100 people walking against hate and hunger from one end of India to another, through heat and rain and now the harsh cold, had been spotted. There was a big push as the ring crossed us, and we struggled to keep our balance. Waving at the crowds, looking up at those who had gathered on the highway and talking to the person to his left all at the same time, Rahul was on his way. On the dot: 3.30pm.

We and many other people followed, walking as fast — almost running — as we could manage in the thick winter air that makes you breathless. There were small knots of people lining the road that had been taken up completely by the two rings — the white one for the cameras and the blue one for Rahul Gandhi. You could walk behind them or run ahead of them, it was difficult to walk with them. You got pushed by the security into the crowd waiting on the broken pavements; “Stay away, stay clear, you will get hurt,” the warning rang out every now and then.

Abruptly, the march stopped outside a steel factory. Rahul was addressing the media, someone said. Later, pictures appeared of him with factory workers. Whatever it was, the brief stop gave us time to catch our breath. Before we started again.

This repeated itself several times over. Brave a big push and stay on your feet as the walk begins, find a place and start jogging, catch your breath when it halts briefly and then start again. This is what everyone was doing. The shoes of one of the PRTC youths came off, he dropped out and quickly put it on, then ran to take his place and catch the rope.

In the “D” with Rahul were Warring, former chief minister Charanjit Singh Channi, other leaders, walkers and people who came to talk to him. All around were alert volunteers, who looked like they were from the Youth Congress, running with the ring, helping with crowd control, trying to see no one got hurt, while also taking to Rahul people who wanted to meet him, pose for a picture or shake hands.

Atithi Devo Bhava — it is a concept many Indians have grown up with, but one that is getting lost in an age where it is bad form to visit even friends and family without first calling. Watching the Yatra volunteers welcome complete strangers who had joined them for a while and look out for them, offering food and trying to shield from the crush, the advice handed down from the Upanishads came to mind.

The idea of a yatra is not new in India. Mahatma Gandhi’s Dandi March set us off on our journey to freedom. The Adi Sankaracharya walked the length and breadth of the country. Most of our pilgrimages require long treks, although often bypassed these days with helicopter rides or, where that is not possible, rides on mules. If Bharat Mata is the millions of people who make up this country, as Jawaharlal Nehru had said, then the Bharat Jodo Yatra is the Indian’s pilgrimage.

A visit to a gurdwara in Chandrakona, tucked away in West Midnapore, had left an impression on my young mind years ago because it marks the place where Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, had halted on his way to the Shri Jagannath Temple in Puri. He walked all the way here from Punjab, I remember asking in wonder. Here I was, walking with people who had walked all the way from Kanyakumari to Punjab.

“Chal, chal ke chaleya geya (he has gone by, walking),” a greying policeman had told us in the morning. While trying to find our way through the traffic jam, we had asked if Rahul had crossed that road or was yet to come.

Many waiting on the side of the Gobindgarh-Khanna road waved Congress flags. Others were shopowners who came out to watch or people who gathered on terraces of houses. At a wedding venue, a small party in finery stood to see the walkers go by. There were also many who were going about their daily business, shopping or returning home from work, not paying much attention to the group striding down the road.

Along the way, there was a small tent where bananas and oranges were being handed out to the walkers. Beyond that point, you had to watch out to make sure you did not slip on the banana peels, besides trying not to stumble on the uneven pavements.

Two and a half hours after we began, we were at our destination: Khanna — home to arguably Asia’s largest grain market. In front of us were giant screens beaming the Yatra feed and welcoming the Yatris. On the road was laid out a red carpet with flower petals showered on it. It was dark already, but the time was 6pm. The Yatra had arrived before schedule.

We got into our cab and headed back to Chandigarh, feeling strangely warm on a winter evening.

What did we achieve, taking time off work, increasing our carbon footprint and marching 9km down a road only to drive back? I don’t know. But we walked under the Tricolour, for the India it symbolises — a country of peace, love, courage, compassion, equality, diversity, self-respect and freedom. Not to walk was not an option.