Like Parashuram, he has an axe to grind. And Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd brought it down heavily, but for a different people altogether, when he was in Calcutta last month.

The redoubtable Dalit writer-activist went straight for what still constitutes a major component of Bengali pride: “Bengali intellectualism”. He said: “If you look at the present BJP-RSS-VHP ideological formations, the RSS was formed in 1925 by Maharashtrian Brahmin thinkers including [K.B.] Hedgewar, but the political Hindutva force came from Bengal. From the writings of Bankimchandra [Chattopadhyay] to the emergence of Syama Prasad Mookerjee, the first Jan Sangh president.”

Shepherd had been invited by Pratyay Gender Trust and Sanhita, organisers of the Rituparno Ghosh Memorial Lecture, to deliver this year’s talk. (Pratyay is a collective for transgender rights and Sanhita works for women’s rights.) He announced that he would speak on “Caste, Gender and Democracy”. He spoke about the advent of nationalism in Bengal, a moment in colonial history crucial to the formation of modern Bengali identity, and pointed out in his crusty style that Bengali intellectuals from that moment had nourished the Hindu patriarchal ideology by eliding caste.

Shepherd, 66, was born Kancha Ilaiah. He added the last name as a reference to the community he was born into — the sheep-grazing and goat-herding Kuruma Golla caste of Papaiahpet, a village in Telangana. “Ilaiah” derives from the name of the caste deity, Inoli Mallanna. So the name he has taken on, an English word with a Christian sense, positions him far away from Hindu gods who filled him with terror in his childhood, and from the high-caste surnames that dominated the history of intellectualism he was gunning for that evening.

“My understanding is that there was something basically wrong in the way Bengali intellectuals constructed nationalism. And the whole regional understanding of the nation,” Shepherd continued.

He said this was different from what had happened in other parts of India. “Two strains contended very strongly in the Bombay and Madras provinces. The present-day RSS emerged, but equally the anti-caste movement emerged there,” said Shepherd.

140th birth anniversary celebrations of Periyar at Coimbatore recently PTI

But Bengal, despite its “liberalism”, represented a continuity with the earliest caste traditions formulated in the four varnas from the Rig Veda. Though Buddhism was very near Bengal, it failed to make a breach, he pointed out.

This had huge implications for caste and gender. Both categories have one thing in common — labour. This labour of women and Shudras was instrumental in birthing cities, transforming villages. He spoke about how in the world of agrarian work there was less discrimination because of gender and how women were at the forefront of agricultural production. “In the classical Hindu texts, there were both approval and disapproval for the transgender person,” said Shepherd. Bengal, being the Brahminical place that it was, missed these nuances.

Sanskrit scholars ruled here. Pointed out Shepherd, “Even Vivekananda’s grandfather was a Sanskrit scholar. And look at my father, grandfather, they were scholars of sheep-rearing, goat-grazing. Scholarship was there. Not in letters.” So how did the Communists miss this issue? According to Shepherd, they missed it because they did not accept the notion of identity politics. “They never accepted that caste is an Indian reality. Caste was subsumed by class.” They also ignored gender equality.

The Communists seemed to believe that whenever the full revolution came about they would have everything. “But that is not correct... They should have initiated an understanding and identification of the role of identities. They should have located the caste structures and the gender structures in their programmes. And that would have led the nation towards more egalitarian issues than what the Right-wing people today are doing.”

Even today, he said, young Bengalis remain unaware of these differences.

Shepherd used to teach Political Science at Hyderabad’s Osmania University and is currently director of the Centre for Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy at the Maulana Azad National University in Hyderabad. He stressed that while Rammohun Roy, Tagore and Vivekananda are known in every part of the country, whenever he asks Bengali students if they have read Mahatma Phule or Periyar, they don’t seem to be even familiar with the names.

He pointed out another problem staring contemporary Bengal in the face. Shepherd said, “The 2021 census, for the first time after 1931, will enumerate all OBCs. I think the BJP will try to enlist OBC support in Bengal. Even Mamata Banerjee may not be able stop the OBC identity construction by the BJP. If the BJP organises OBC/Dalits along caste lines and declares an OBC CM candidate, they will come to power.”

That August evening it may have seemed to many that Shepherd was making sweeping statements, but he was speaking from his own life. Caste, religion, gender — and nomenclature — had ganged up to beat him down all his life, he said. And the scars showed even as he hit out at each of these.

He spoke about how his name was his earliest torment and one that almost broke him, as was Goddess Saraswati. Of course, as he sat on the stage, in his dark suit, firing away in English, he was a living embodiment of all that he was denied by birth.

Shepherd and his brother were first-generation learners. This happened despite their mother, Kancha Kattamma — a feisty matriarch, who ran the household and fought the forest and police officials to keep her flock of goats and sheep together — being told that Saraswati would destroy them for this act of transgression. Lower castes were after all not supposed to study, certainly not Sanskrit, he has written in his forthcoming memoirs to be published by Calcutta-based publishers Stree-Samya.

In little Kancha Ilaiah’s mind, Saraswati was this sinister goddess who could even kill. His eldest brother had died after he began his education. His community considered it Saraswati’s curse.

In school, he and his brother Kattaiah were humiliated openly for their names. “I am not here to teach Ilaiahs, Yellaiahs, Pullaiahs, who know nothing about education, whose brains have nothing to do with education,” declared their teacher. A reference to the fact that higher caste names did not end with the “shameful ah”.

And then one day, as a college student, he stumbled upon Isaiah Berlin. Not the great philosopher himself, but his name. Isaiah rhymed with Ilaiah! “To my surprise, he was a globally renowned living thinker. I looked at the name again. I felt as if I were Isaiah, not Ilaiah. That day I wrote my name in full as he did his: Ilaiah Kancha, not just Ilaiah K. And it sounded new.” Thus Kancha Ilaiah delivered himself.

“Now, Saraswati is the goddess of English,” said Shepherd. “But even today Saraswati does not want to give us English. This is a problem.” Dalits had to locate their goddess in Savitribai Phule — the first educated Shudra woman.

Without English, the Dalit cannot aspire to enter into a domain that empowers him. No boardroom discusses anything in Bengali or Tamil or Malayalam. The Dalit’s is a rare presence in the boardroom and the Dalit woman is almost absent.

“It is in this context that we want to construct our own ideological framework of decasteising India and degendering Indian civil societal relations and democracy,” he said. “In this we need to struggle for English education. On October 5, we celebrate Indian English Day at Osmania University. We fight for English [to be taught] in all government schools and the deprivatisation of English education,” he added.

SC/STs, OBCs and the women of India need to evolve a common language, literally. Unless they speak to each other, nothing is going to change. He concluded, “My appeal to Bengali intellectuals is: please start a serious discourse about caste in Bengal. In Bengal, there is a caste cancer without diagnosis.”

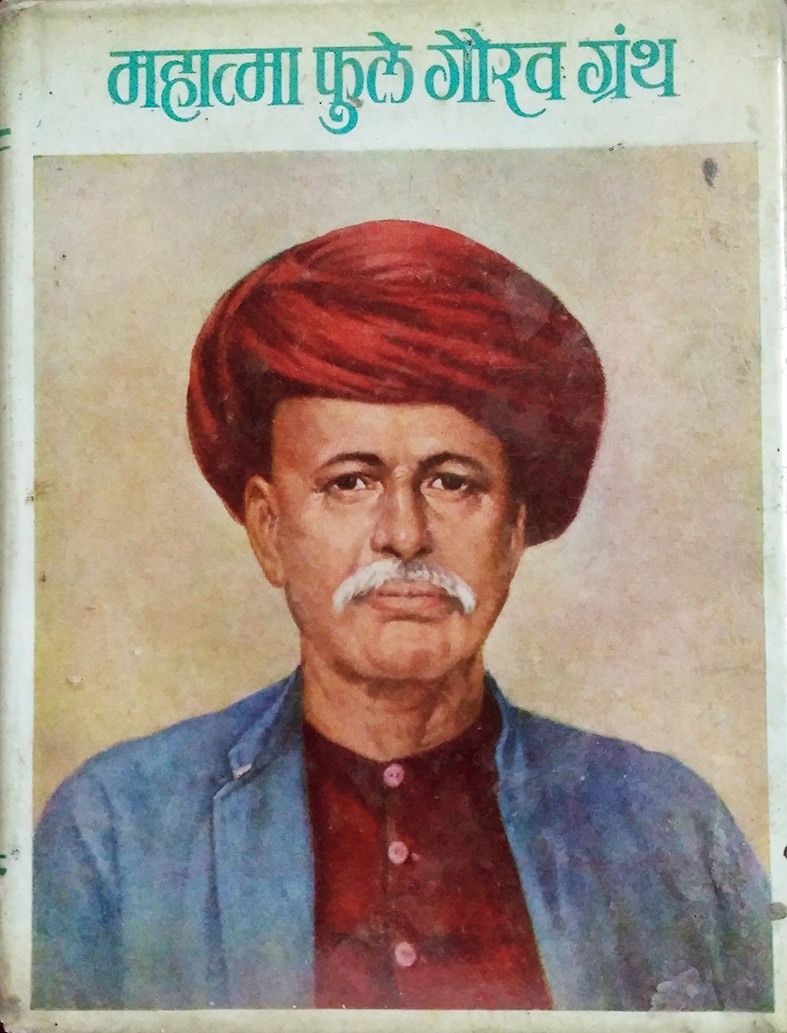

Thinker and reformer Jyotirao Phule File picture