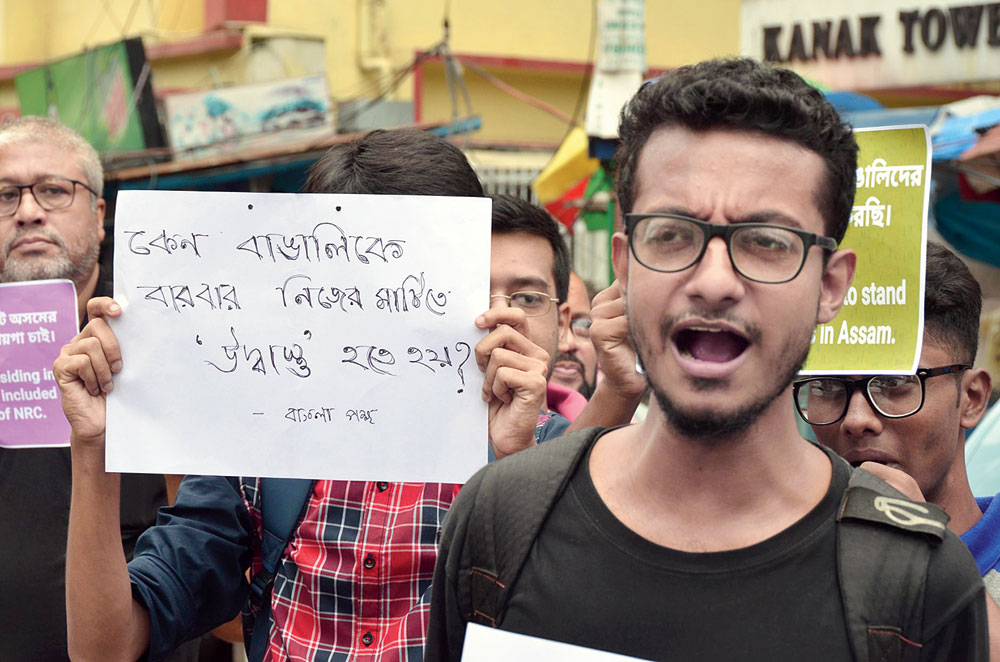

Bangla pokkho means for Bengal. “We are doing this for Bengal and the Bengalis,” says Kausik Maiti, one of the members of the organisation named Bangla Pokkho. It has been in the news for what has been dubbed as anti-Hindi activities. Some also say it is an anti-BJP pressure group. On December 15, the organisation’s flag was unveiled for the first time in Burdwan. Does that mean it is a political party now?

Maiti clears the air. According to him, Bangla Pokkho is a political organisation that fights for the rights of Bengalis but is not considering joining active politics, at least for now. As for being anti-BJP, he says, “We are not anti-BJP, it is the BJP that is being anti-Bengali by promoting Hindi Hindu Hindustan. We are against that ideology. They are anti-India too. We are against any organisation whose ideal is religious fundamentalism.” He cites the excessive celebration of Ram Navami in Bengal and how the state BJP boss, Dilip Ghosh, brandished a proud sword.

We are sitting in a coffee shop in central Calcutta. Maiti, who is employed in the IT sector, is with Siddhabrata Das, who works in the insurance sector, and Anirban Banerjee, a lawyer. Each of them has a phone in hand and is scrolling through social media feeds and showing me photographs — of someone cooking fish, someone else’s selfie with a plate of chicken curry, a close up of an egg fiery curry.

Says Maiti, “The Indian Railways had decided to mark October 2, Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday, as Vegetarian Day. So we celebrated it as Non-Vegetarian Day. We encouraged people to put up pictures of non-vegetarian food on social media as a form of protest.” Banerjee interjects, “This is appeasement. Gandhi does not represent vegetarianism.”

Whether it was their protests that did the trick or something else they cannot say, but in the end the Indian Railways rolled back its plan. This is not the first time Bangla Pokkho has protested. Since its inception in January 2018, the organisation has raised many an issue. It has demanded that banks issue forms in Bengali and the Bengali language option be introduced in ATM machines, on milestones, for road directions, on highway signage and on metro cards. The demands are all Bengal specific, of course, and most of these have been met with since.

Says Banerjee, “It is already there in the Reserve Bank of India guidelines that bank forms should be available in regional languages, but it wasn’t implemented here. We were not asking for something that was not there. We are not anti-Hindi, we just want Bengali where it is needed.”

Bangla Pokkho was not the brainchild of any one person. “We were all doing things in our individual capacities. I was talking about Bengali nationalism and rights of Bengalis, he [Banerjee] was talking about something else,” says Maiti. Das chips in, “Basically, it all started with social media and then assumed a physical form.”

In a way, the organisation first came into public eye when it made a noise about the West Bengal Police Constable examination. Two groups had filed a legal petition that the exam be in Hindi and Urdu, besides English. At this point, Bangla Pokkho entered the scene. Its members campaigned against this demand on social media and wrote to chief minister Mamata Banerjee.

“All other states take the exams in their local languages. If we are not getting a chance in other states, then why should outsiders come here, write exams and get our jobs,” asks Das. In April 2018, the state government announced that the exam would be in Bengali and additionally in Nepali for Darjeeling.

Maiti points out that after this, the Trinamul government also declared that the exam for the recruitment of assistant sub-inspectors would be in Bengali and Nepali. He says, “And if it is in Santhali too, we will be happy. We want equal rights for Santhali, Rajbangshi, everyone.” Das adds, “We support any language which has roots in Bengal.”

But the toughest fight, and one which continues, is against the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test or NEET, the national level medical entrance examination. Das talks about how Narendra Modi was one of the strongest voices against NEET and wanted the inclusion of Gujarati language when he was the chief minister. He lowers his pitch and laughs, “See certain changes will happen when the CM becomes the PM.” Bengali question papers were made available from 2017 but not only were the questions different from the English and Hindi papers, the standard of translation too was poor.

At this point, the discussion turns a little shrill. Banerjee, who is the lawyer in the group, starts to talk about the domination of the Hindi belt in Parliament, the consequence of nothing but a high population density, and how it made Hindi the elevated, important language that it is today.

I point out that I smell something off here; something that smells a bit like a good fight turning sour. Even when I had called to fix the interview, I had been told, “No English or Hindi please.” Does this mean Bangla Pokkho is going to force the non-Bengalis of the state to speak the language?

Of course not — the denial is swift, earnest. There must have been a misunderstanding. Banerjee says, “This is where we are different from a Shiv Sena or a Maharashtra Navnirman Sena. We don’t want to beat up people and send them back to their own states. We want rights for Bengalis, that is the only thing.” And Das says, “We are so liberal that we even want to open a front of Bangla Pokkho for people whose mother tongue is not Bengali but have been staying in Bengal for years. If you love my state soil, I consider you as our own.”

The group, which claims to have over two to three lakh supporters, has members from across political parties. “We have members from CPI(M), CPI(ML), Trinamul,” says Das.

And apart from what is in the realm of the ideal, what is it that Bangla Pokkho does now and what is this language struggle tethered to? To all, but in particular the people in the villages, says Das.

He talks about how language creates a rich-poor divide in a rural setting. “It becomes a class struggle, wherein you have segregated people by saying ‘Learn Hindi or you will be poor and you can’t have the fruits of the economy’. The Constitution does not give Hindi the national language status nor does it say that India is a Hindu state, then why will these things be thrust upon us?”

Maiti belongs to Gholdigrui village in Hooghly district. He talks about how village people struggle with bank paperwork. How they have to pay agents to help them out, only because the forms don’t come in the language they are conversant with. He continues, “I have seen my mother read and write Bengali fluently but she feels like an illiterate when it comes to bank and insurance forms.” Das claims that the literacy rate in Bengal is around 78 per cent, but the moment one makes Hindi and English the recognised mode of communication, the literacy rate dips to maybe 20 per cent. “We are doing all this from a socio-economic perspective also,” says Das.

But all this is talk. What do Bangla Pokkho members actually do on the ground? Maiti says members move from village to village, district to district spreading awareness about one’s rights as a Bengali.

He says, “We try to let people know what we are being deprived of. Hindi imperialism is making slaves of us. It is not only about linguistic rights, but also about education, jobs, economy. We want our share in central government jobs, colleges and businesses. We make people aware how a literate Bengali becomes illiterate for not having knowledge of Hindi and English. And we appeal mainly to young people to come forward and fight. We arrange meetings, public gatherings at street corners, seminars, etc. We want to live as first-class citizens of this country.”

The group calls itself “co-federalists” and demands a “loose Union and strong states”. Banerjee, who spouts Marx, says Bangla Pokkho is fighting for a cause that the communists should have taken up and which the communists in Kerala are pursuing but not the ones in Bengal. “We don’t want Bengali imperialism in India either,” he clarifies. “We are basically fighting for equal rights.”

He talks about a similar organisation in the South. Karnataka Rakshana Vedike has 1.5 crore members all over the world. Says Banerjee, “They can influence government policies. They have influenced the state government elections and that’s the place we want to reach in the next five years.” And, onward march.