The Supreme Court has unanimously awarded the disputed site in Ayodhya to Ram Lalla Virajman (baby Ram) and empowered the Centre to build a temple there but ruled that the demolition of the Babri Masjid was “an egregious violation of the rule of law” and a “wrong (that) must be remedied”.

A five-judge constitution bench directed the central government to constitute within three months a trust to facilitate the construction of the temple.

It also asked the government to allot the Sunni Central Wakf Board a five-acre plot in Ayodhya, outside the disputed 2.77 acres, to build a mosque.

Saturday’s verdict set aside a 2010 Allahabad High Court judgment that had trisected the disputed plot and handed equal shares to the Nirmohi Akhara, Ram Lalla Virajman (represented by a VHP leader) and the Sunni Central Wakf Board.

The 1,045-page judgment, delivered by the bench of Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi, Chief Justice-designate S.A. Bobde and Justices D.Y. Chandrachud, Ashok Bhushan and Abdul Nazeer, relied mainly on archaeological evidence.

The court said the Hindus could establish they had “exclusive” access to the disputed land while the Muslims did not furnish proof that their possession of the disputed structure of the mosque was “exclusive”.

It said the 5 acres should be allotted to the wakf board “either by… the central government out of land acquired under the Ayodhya Act 1993, or… the state government at a suitable prominent place in Ayodhya”.

The Sunni Central Wakf Board would be at liberty, on the allotment of the land, “to take all necessary steps for the construction of a mosque with other associated facilities”.

The court said it was passing the land-allotment directive by exercising its special powers under Article 142 to render justice to the Muslim community since the Babri Masjid was demolished despite the dispute pending before the top court.

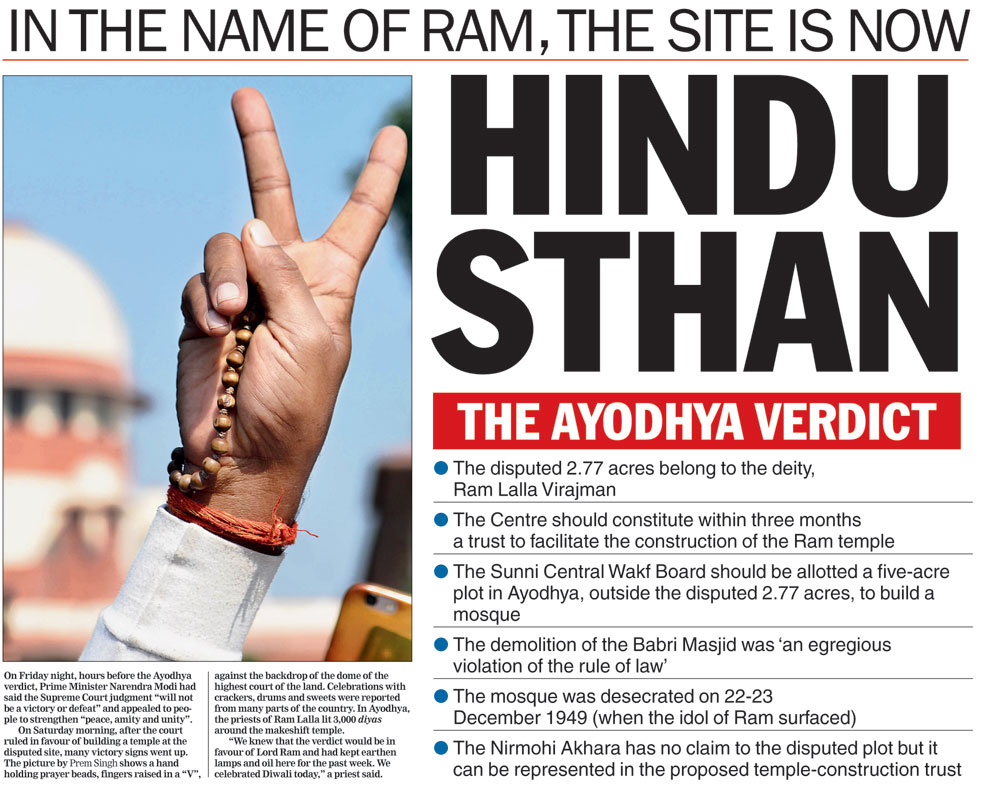

The Telegraph

It further invoked Article 142 to provide the Nirmohi Akhara with representation in the proposed temple-construction trust despite rejecting its claim to the disputed plot.

The bench said there was archaeological evidence to support the claim of a pre-existing structure “suggestive” of a Hindu temple at the place, besides the testimony of travelogues and other historical material, whereas the Muslim parties could not produce any evidence against the rival claim.

The court said the ASI report indicated that “the pre-existing structure dates back to the twelfth century; and the underlying structure which provided the foundations of the mosque together with its architectural features and recoveries are suggestive of a Hindu religious origin comparable to temple excavations in the region and pertaining to the era”.

The court added that the conclusion in the ASI report about “the remains of an underlying structure of a Hindu religious origin symbolic of temple architecture of the twelfth century AD must, however, be read contextually with the following caveats”.

While the ASI report has found the existence of ruins of a pre-existing structure, the report does not provide “the reason for the destruction of the pre-existing structure; and whether the earlier structure was demolished for the purpose of the construction of the mosque”.

“Subsequent to the construction of the ancient structure (temple) in the twelfth century, there exists an intervening period of four hundred years prior to the construction of the mosque,” the bench said.

It added: “Though the case of the plaintiffs… is that the mosque was constructed in 1528 by or at the behest of Babur, there is no account by them of possession, use or offer of namaz in the mosque between the date of construction and 1856-7.

“For a period of over 325 years… since the date of the construction of the mosque until the setting up of a grill-brick wall by the British, the Muslims have not adduced evidence to establish the exercise of possessory control over the disputed site. Nor is there any account in the evidence of the offering of namaz in the mosque over this period.

“On the contrary, the travelogues (chiefly Tiefenthaler and Montgomery Martin) provide a detailed account both of the faith and belief of the Hindus based on the sanctity which they ascribed to the place of birth of Lord Ram and of the actual worship by the Hindus at the Janmasthan.”

(Joseph Tiefenthaler, an 18th-century Jesuit missionary, was one of the earliest European geographers to write about India. Robert Montgomery Martin was a 19th-century Anglo-Irish author and civil servant who wrote a history of the British colonies.)

Further, the court said, the Hindus had established that they had exclusive and unimpeded access to the disputed land in both the inner and outer courtyard of the pre-existing structure.

“There is no evidence to the contrary by the Muslims to indicate that their possession of the disputed structure of the mosque was exclusive and that the offering of namaz was exclusionary of the Hindus,” it said. “Hindu worship at Ramchabutra, Sita Rasoi and at other religious places including the setting up of a bhandar clearly indicated their open, exclusive and unimpeded possession of the outer courtyard.”

However, the bench rejected the Hindu parties’ claim that the Muslims had abandoned the mosque and ceased to perform namaz at the site.

On the Babri Masjid demolition, the court said: “On 6 December 1992… the destruction of the mosque took place in breach of the order of status quo and an assurance given to this court. The destruction of the mosque and the obliteration of the Islamic structure was an egregious violation of the rule of law.”