When Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of India abruptly changed her country’s constitution in 1971 and abolished the Privy Purse, a government allowance for the country’s former princely rulers, she also moved to nationalize their storied treasuries. Among the maharajahs, nizams and nabobs that once ruled the subcontinent, this set off a frenzy as they scurried to bury the family jewels.

For centuries, the rarity, scale and grandeur of Indian jewels was so great that many became iconic objects. Take the Patiala Necklace, a tiered ornament resembling draperies of gems. Designed by Cartier, it featured an astounding 2,930 diamonds and centered on a single rock the size of a walnut. Or consider the Indore Pears, two stupendous and closely matched diamonds owned by Maharajah Yeshwant Rao Holkar II, a glamorous westernized ruler whose kingdom was in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.

Indian princely patronage long set a global standard of splendor for both artistry and ostentation in the jewel trade. Yet in the decades after the Privy Purse, most of the big rocks seemed to have vanished underground. Legend has it that members of formerly royal families stashed their jewels in Swiss vaults, pawned them on the black market or hid them in flower pots.

Bling on a royal scale largely disappeared. Or so it seemed until a fresh cadre of princes heaved into view: oligarchs. The richest of these by orders of magnitude is Mukesh Ambani, the chair of his family’s megacompany Reliance Industries. Ambani’s personal fortune is estimated by Forbes at a staggering $115 billion. Despite his vast wealth, few outside India had heard of him — that is, until March 1, when he hosted a three-day party to celebrate his son Anant’s wedding in July.

Everything about the prewedding affair was on a princely scale: the guest list of 1,000, including boldface names like Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates and Ivanka Trump; a glass palace specially constructed in Ambani’s hometown, Jamnagar, in the western state of Gujarat; and Rihanna’s first public performance in years.

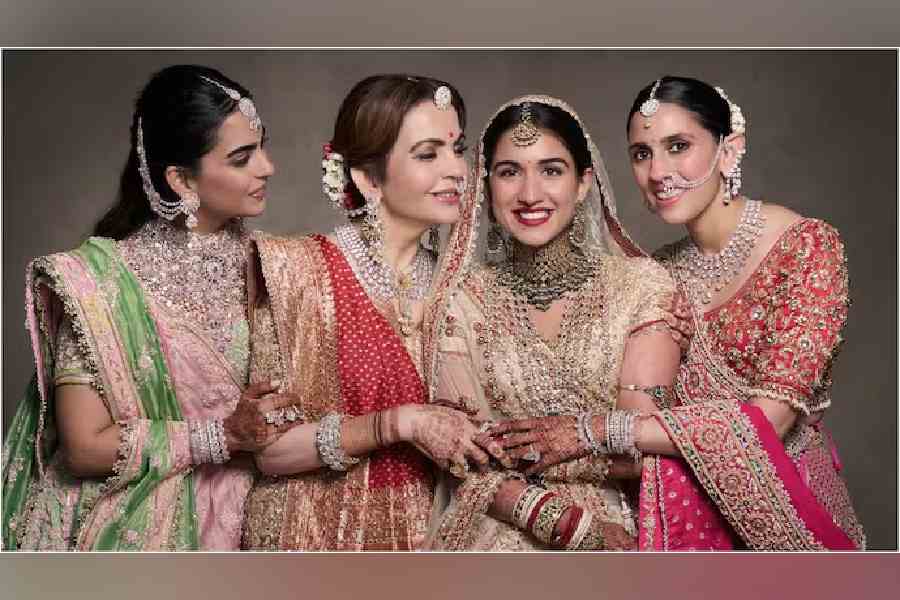

Rihanna’s reported $6 million payday hogged the headlines, but what lit up at least one obsessive corner of the internet was the Ambani jewelry. This included necklaces and earrings and rings and hair ornaments of a size and grandeur seldom seen publicly since the days of the Raj.

“It was almost like the time of maharajahs 100 years down the line,” said Pramod Kumar, an archivist and a founder of the museum consultancy EKA. He is also keeper of topophilia.india, an erudite Instagram account that is catnip for Indophile aesthetes.

Kumar’s sleuth work traced a possible source of the two most gobsmacking gems seen at the Ambani prewedding celebration: massive step-cut Colombian emeralds roughly the size of Popsicles. Draped one below the other as pendants to a diamond necklace, they were worn one evening by the bridegroom’s mother, Nita Ambani. The bigger one was “of 562 carats,” Kumar wrote in an Instagram post, adding that the weight of the smaller stone was a mere 303 carats.

Whatever their source, those emeralds were just two among many gems on display throughout an event at which the jewels often had greater star power than their wearers.

“That emerald necklace was what caught everyone’s attention at first, but it was all almost unfathomable,” said Stellene Volandes, the editor-in-chief of Town & Country. She noted the scarcity represented by ropes of the rarest natural pearls from the Arabian Sea; necklaces in the heavy, ornate rani haar style studded with diamonds; and headpieces known as maang tikka, made with deep green emeralds from the storied Muzo mines.

“You’d be very hard-pressed to find comparables for the sheer size and horsepower” of the jewels at the Ambani prewedding party, said Nico Landrigan, the president of the Verdura jewelry house in New York. “The Indians are a jewelry-obsessed culture in a category all their own. So you can only imagine what the actual wedding will bring out.”

Before the wedding, scheduled for July 12 to 14 in Mumbai, there was yet another lavish preparatory celebration and opportunity to flaunt big rocks — a cruise from the Tyrrhenian Sea in Palermo, Italy, to the Mediterranean in Cannes, France, on an ocean liner whose 2,400 staterooms had been retrofitted for the Ambanis as three-bedroom suites for 800 invited guests. “Basically, what the Ambanis are doing is displaying a kind of old-style Hollywood glam,” said Kumar of EKA. “You don’t see that with any other current billionaire moguls in Europe or America, at least not in the public realm.”

For Daniela Mascetti, the former chair of Sotheby’s jewelry division in Europe and an author of “Understanding Jewelry,” a bible of the trade, the group more aptly compared to the Ambanis is the robber barons of the Industrial Age. “You have to look back to Vanderbilt or Gould, who also wanted big door-stoppers,” Mascetti said from London. “Let’s put it in a nice way,” she added. “If you are new money and you want to display wealth, you go big.”

Yet it is not altogether that simple. Certain Ambani jewels were crafted using the whopper stones, but that is not to suggest that the determining factor in commissioning them was size. “There is tremendous artistry in the work,” said Volandes of Town & Country.

Much of the Ambani jewels were designed by Viren Bhagat, among the more refined high jewelers, though also an assiduously private one. More than the size of individual stones like the stepped-cut emeralds, few save a detective like Kumar could predict their origins.

“Being one-off is of the greatest importance in that world,” Francesca Amfitheatrof, the creative director of high jewelry and watches at Louis Vuitton, said recently from St.-Tropez, France, where she was debuting her latest collection.

“To be able to source things that are so unique and outstanding, honestly, only an emperor has that possibility anymore,” she said. “It’s completely maharajah-like. It’s imperial.”

The New York Times Services