Prime Minister Narendra Modi may today rant against “Lutyens’ Delhi culture” but his spectacular journey of the past two decades may not have been possible without a man who purportedly personified this so-called culture.

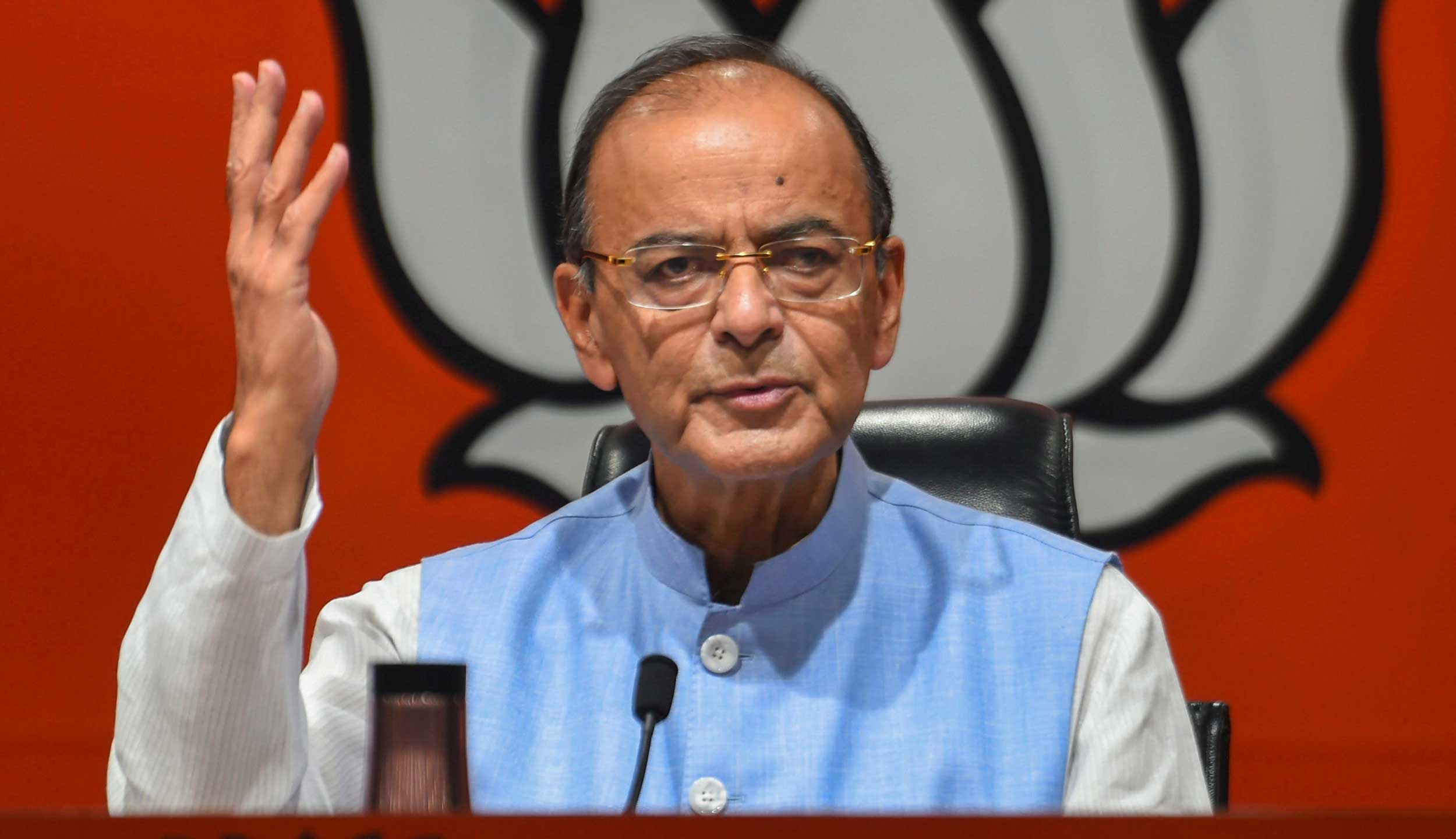

The English-speaking, smooth-talking, urbane and well-networked Arun Jaitley.

Jaitley could talk and manoeuvre the BJP out of any tight corner, right from the Atal Bihari Vajpayee years to the Modi era. Modi had himself been a beneficiary of this when Vajpayee was planning to axe him as Gujarat chief minister after the 2002 pogrom.

Jaitley, the man about town whose province of influence straddled the world of politics, judiciary and cricket and whose helpful nature had earned him IOUs aplenty, was the BJP’s key trouble-shooter till the onset of the slash-and-burn politics of recent years.

His penchant for lending a helping hand to political friend or foe had earned him the reputation of being a Congress-type politician.

Not all those he helped were people with connections. Some of them were ordinary folk, like his secretarial staff for whom he built a block of flats or those he befriended first in Delhi’s Panchshila Park and then Lodi Garden during his morning walks.

Jaitley would arrive with a big flask of tea for his friends and there would be more talking than walking, with the BJP leader doing most of it.

His birthdays used to be celebrated in the park. He could set up an adda — an “off-the-record durbar” in media parlance — anywhere: in his drawing room, the debriefing room at the party headquarters, a park or the Central Hall of Parliament.

The joke in Parliament’s corridors was that no other finance minister had spent so much time chatting with journalists as Jaitley did, till BJP president Amit Shah got elected to the Rajya Sabha and began holding forth.

His detractors would often wonder how a finance minister found the time to hold his durbars, keep himself so well informed about the goings-on in every political party, and do the fire-fighting for his party.

“He was a great raconteur with an elephant’s memory. He loved talking, and keeping himself abreast of whatever was going on with the people he knew,’’ Harish Gupta, journalist and Jaitley’s friend of 49 years, said. “He remembered things about my life that even I had forgotten.’’

Several of his associations were more than four decades old, as with former Samta Party spokesman Shambhu Srivastava, who first met Jaitley during their student days back in the 1970s.

Jaitley, then a hugely popular Delhi University students’ union president, was one of the national conveners of the Chhatra Sangharsh Samiti formed by RSS student wing ABVP and the socialists, which preceded Jayaprakash Narayan’s call for “Sampoorna Kranti (Total Revolution)”.

Many of his contacts across parties go back to those heady days of student politics. His cellmate in jail during the Emergency, socialist Vijay Pratap, had an interesting aside: “Jaitley’s first introduction to politics, ironically enough, began at a Left-oriented study circle in Delhi University.”

Jaitley had never been with the Sangh but his debating skills during his student days — at the Shri Ram College of Commerce and Delhi University’s Faculty of Law — got him the ABVP ticket for students’ union president in 1974.

Out of jail, Jaitley and Vijay Pratap remained in touch. “Like alumni associations, we had an informal association of jail ward mates and we used to meet occasionally,’’ Vijay Pratap quipped, remembering with nostalgia a political era when friendships could bridge ideological divides.

Srivastava, who came into regular contact with Jaitley in the 1990s when they would lock horns at television studios, said: “He was a great host. All of us who knew him well have lost count of the number of meals we had at his East of Kailash house.”

Jaitley was the typical old-school politician: “ambitious but not driven’’ the way the Modi-Shah duopoly is, enjoying the good life with a passion for cricket and good food, and even marrying into a Congress family. His father-in-law was a two-time MP and six-time MLA from Jammu and Kashmir.

Known as Delhi’s “chief of bureau’’ with the ability to ensure he got very little negative coverage personally, Jaitley had had his earliest contact with the media during the Emergency, courtesy The Indian Express publisher Ramnath Goenka and lesser known journalists.

He built on that network, with his access to the multiple worlds of politics, corporate houses and cricket making him the media’s go-to guy.

He was therefore the obvious choice as spin doctor when the BJP needed to battle perceptions — a role he carried into the Modi years through his blogs.

Congress politician Jairam Ramesh, who locked horns with Jaitley in the Rajya Sabha often enough, once called him “Bedi+Pras+Chandra+Venkat” for his “extraordinary spinning skills’’. He recalls that Jaitley enjoyed the description hugely.

Bishan Singh Bedi, Erapalli Prasanna, Bhagwath Chandrasekhar and S. Venkataraghavan made up Indian cricket’s famous “spin quartet” of the late ’60s and the ’70s.

Having completed his law studies after the Emergency, Jaitley built a career for himself in corporate law, which gained him a whole circle of high-flying friends.

His client list reads like a who’s who, and when V.P. Singh became Prime Minister in 1989, he got picked as additional solicitor-general with charge of the Bofors investigation at the age of 37.

Politicians with a finger in India’s cricket administration pie are dime a dozen but few among them have ever shown the kind of passion for the game as Jaitley did, according to people familiar with the domain.

As with his other spheres of influence, so with cricket: Jaitley kept open house for cricketers and was ever keen to meet new blood, player or cricket journalist.

All of it contributed to the aura around him, complete with the smugness of a man who could lawyer up in a heartbeat to win an argument.