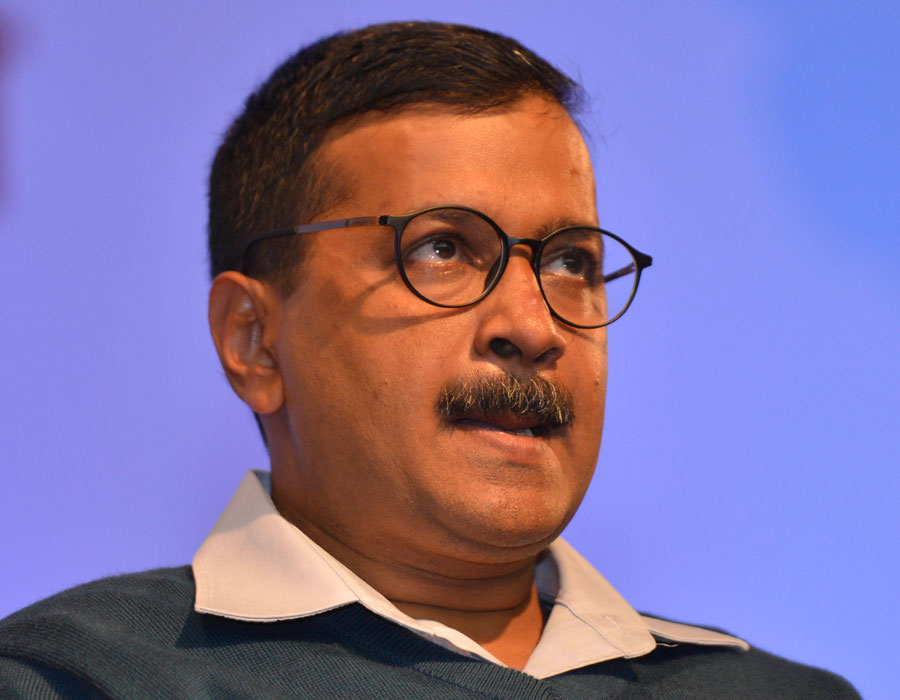

If smiles won votes, then the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) leader, Arvind Kejriwal, would win the Delhi Assembly polls hands down. Gone are the days when Kejriwal was New India’s angry young man, with a muffler and a questioning stare, who publicly burned copies of a law he opposed, and went on fasts and dharnas. The new Kejriwal smiles and even asks BJP voters to reward the AAP for the Delhi government’s work in power tariffs, water, health and education.

The days of being vociferous street dissident, scourge of the establishment, towncrier against power politics are behind him. The new Kejriwal is a family man, who is shown praying, a humble son who funds pilgrimages of Delhi’s elderly, and welcomes Delhiwallas from any party into his fold.

Bets are out on whether Kejriwal 2.0 will click. After bringing the Congress to its knees through the India Against Corruption movement in 2011 and 2012, he quickly moved to form a political party against his own declarations not to join power politics and against the wishes of the movement’s face, Anna Hazare. After forming the AAP in November 2012, Kejriwal led militant agitations against higher power tariffs, against the Congress government in Delhi — already shaken by widespread public protests against the gang rape and murder of a paramedical student in December that year.

A little over a year into its formation, the AAP ended the Congress’s 15-year rule in the capital. The minority government — backed by the Congress — lasted only 49 days after Kejriwal resigned over differences with the Congress over his government’s bill to create an all-powerful ombudsman. As chief minister, he even sat on dharna outside Parliament just before Republic Day demanding the removal of cops who did not cooperate with the AAP law minister Somnath Bharti’s vigilante raid on Africans in South Delhi wrongly suspected of running sex and drug rackets.

Although, Kejriwal owned the derisive tag of being an “anarchist”, the 49-day regime made his priorities clear. Water and power were subsidised, and funds were made available for renovation of schools. Even in tickets to candidates, Kejriwal’s will prevailed in favour of choosing winnable candidates rather than activists. “His activism was for governance, and that has been his only goal. That’s what the people of Delhi want. Only individuals who contribute to this goal have space in the party. There is no place for rivalries,” an old AAP hand told The Telegraph.

The AAP failed to win a single seat from Delhi in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls and Kejriwal lost the contest to Narendra Modi in Varanasi. The party’s vote share rose marginally from 29.5 per cent in 2013 to 32.9 per cent. The party, however, won four seats from Punjab and entered Parliament.

Kejriwal’s response was to immediately drive home the point that the AAP was here to stay and deliver on the social sector. The fight against corruption became secondary to his goal of attaining power and delivering on the issues he fought for even before resigning from the Indian Revenue Service in 2006. Voters gave the AAP an unprecedented 67 out of 70 seats, and 54.3 per cent votes in the 2015 Assembly polls. The Congress drew a blank.

Almost immediately, Kejriwal purged the party’s Leftist deviation led by lawyer Prashant Bhushan and academic Yogendra Yadav, who had questioned the selection of candidates and the lack of democracy within the party. Despite the government’s work in schools and in the health sector, the party until 2017 was known mainly for its confrontations with the Centre, and the urge to punch above its weight and be the conscience of India’s body politic — much like the Left had been for the first six decades after Independence.

In 2017, the party drew a blank in Goa where it had campaigned extensively, and although it became the leading Opposition party in Punjab, it became clear that it no longer rode the tide of 2014. In the Delhi civic polls too, the BJP retained its hold on all three municipal corporations. The AAP lost its deposit and seat in the Rajouri Garden Assembly bypoll.

What followed was another rebellion within the party; key leaders of its Rightist deviation, Kumar Vishwas and Kapil Mishra, were sidelined. Kejriwal managed to retain control over the party and once again started to change track, curbing his ambitions and living to fight another day.

The offensive on Modi subsided and Kejriwal’s national ambitions were put on the back burner. With limited contests outside the state, the party focused on consolidating power in the capital while continuing to project itself as the loudest voice on issues like voting fraud. The party won the Bawana bypoll and its victorious candidate, Ram Chander, told media that Kejriwal had heeded his advice of not taking “faltu ka panga” with Modi.

The AAP government now focused on low hanging fruit such as sprucing up government schools with swimming pools and facilities seen only in private schools, doorstep delivery of 40 government services, funding pilgrimages for the elderly. All these started in 2018 and the government’s PR machinery kept the focus on Kejriwal, the individual, as someone who could rise above a party or an ideology to deliver economic benefits.

Journalist and former AAP leader Ashutosh says, “Kejriwal realised that the more he fights, the more he is branded as someone not interested in governance. It certainly helped in getting government work in focus. He is seen as more of a doer now.”

Kejriwal’s switch from an agitator to an administrator has benefited the capital.

Although central grants to the Union Territory were reduced, Delhi’s annual budget doubled from around Rs 30,000 crore in 2015 to Rs 60,000 crore in 2019. The Kejriwal regime turned the fiscal deficit of Rs 3,942 crore in 2013-14 to a fiscal surplus of Rs 113 crore in 2017-18 and the share of public debt to the Gross State Domestic Product fell from 7.23 per cent to 4.89 per cent.

As soon as the AAP came to power, the Centre assumed powers of transfers and postings of bureaucrats in the capital. An almost daily war of words ensued over corruption investigation and appointments by the Delhi government. In December 2015, the CBI raided Kejriwal’s principal secretary Rajendra Kumar, and the CM called PM Modi a “psychopath”. After a long legal battle, in 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that the Lieutenant Governor was bound by the advice of the Delhi government on subjects in the state list. Says a party MP on condition of anonymity, “We did not start the fight. The CM’s image as an angry leader was due to the Centre stopping our work. The CBI and the Enforcement Directorate harassed Arvindji and other ministers. Police filed cases on every other MLA, which fell flat in courts. The SC verdict brought the smile to his face and the faces of Delhiwallas who expected governance from us, and we have fulfilled our promises.”

But even this couldn’t save the party from a total rout in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls. A Kejriwal aide says, “It became clear that this was a BJP versus Congress fight. Delhi’s voters did not see us as a national alternative, and they sometimes apologetically made that clear to us in meetings.”

The AAP tried desperately to align with the Congress. Most of its MPs and key state leaders in Punjab had rebelled in 2018 because Kejriwal was repeatedly apologising to the BJP and Akali leaders to end debilitating defamation cases. An alliance proposal with Congress in Delhi, Haryana, Chandigarh and Punjab came to naught after the Congress’s Punjab CM Amarinder Singh vetoed any sharing of space with the AAP there. In these circumstances, the AAP’s last resort was to launch a campaign on statehood for Delhi.

Result: not only did the BJP sweep all seven Delhi seats again, the Congress was the overall runner-up. The AAP failed to lead in a single Assembly segment while the Congress led in five. The AAP candidates came second in only two Lok Sabha seats with overwhelming margins. Kejriwal answered with the smile offensive. In the run-up to the Lok Sabha polls, the government continuously ran full page newspaper ads of even minor civic works. This was not only stepped up but a new image to brand the CM as a family man emerged. The message: Here is a leader who is putting public wealth in the hands of people at the time of an economic downturn.

Some of the brains behind this change are senior party leader and candidate Atishi Marlena and ad-guru Naru Radhakrishnan, both of whom are on the board of the government ad agency, Shabdarth. Since December, Prashant Kishor’s Indian Political Action Committee has been providing political consultancy to the party. The CM’s outreach is being managed by the Dialogue and Development Commission vice-chairman, Jasmine Shah, and overall strategy for the polls is being handled by minister and Delhi unit convenor Gopal Rai and MP Sanjay Singh.

Referring to home minister Amit Shah’s remarks against Kejriwal last month, the CM told media, “I accept his abuses. But I will not abuse him back. I do not want to indulge in politics of abuse.”

The AAP supported the removal of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status and the Supreme Court verdict on Ayodhya. Although it voted against the CAA, the party took pains to stress that it was anti-poor rather than anti-Muslim. The AAP now recognises that the BJP commandeers the national discourse and its own success depends on how it works around this in Delhi. In a recent TV appearance, Kejriwal even sang the Hanuman Chalisa on the anchor’s request.

The BJP has successfully drawn Kejriwal into the CAA debate with an MP and a Union minister calling him “terrorist”. Until three weeks ago, the AAP expected to repeat its 2015 performance, riding high on its achievements in the social sector, and specific campaigns tailored for every social class and neighbourhood in the capital. The AAP leadership stayed away from the women’s sit-in at Shaheen Bagh and refused to talk about the elephant in the room — communal tension over the mushrooming of anti-CAA stirs in Muslim neighbourhoods as well as traffic jams. After the BJP upped the ante on Shaheen Bagh, however, the AAP has gone on the defensive, and is concentrating more on playing victim to the BJP’s “slurs” against their boss.

Delhi has voted; the verdict will be out in a couple of days. And we shall know whether the last-minute two-pronged campaign of playing the victim of the BJP and simultaneously reminding voters of how Kejriwal improved their lives over the last five years has worked.

It will also be a referendum on both his avatars — the self-proclaimed anarchist and the administrator.